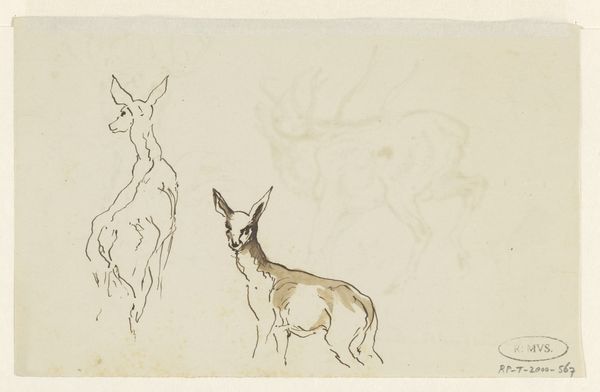

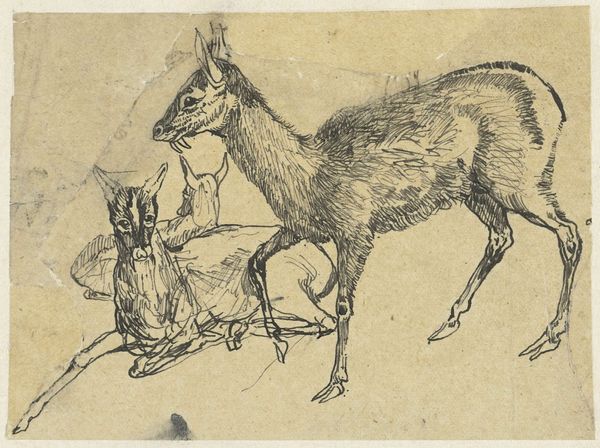

drawing, ink, pen

#

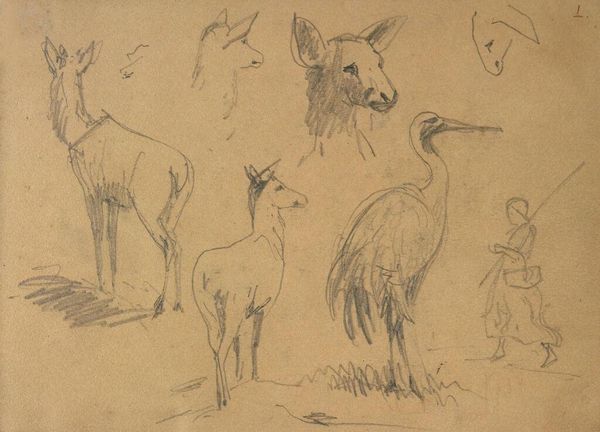

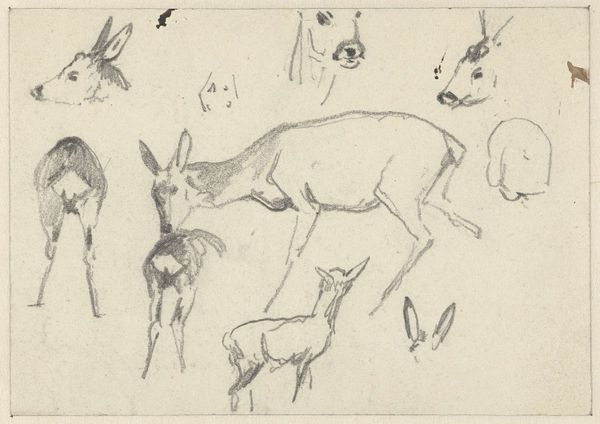

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

animal

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

sketch

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 216 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

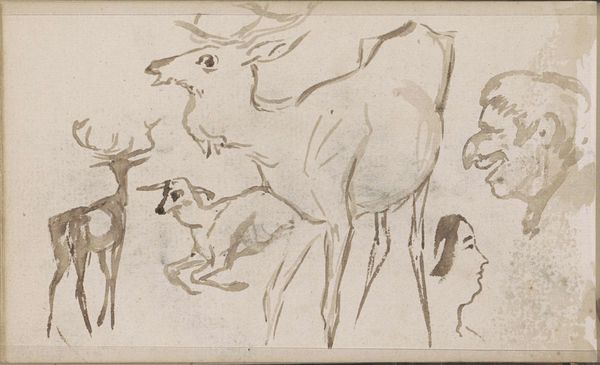

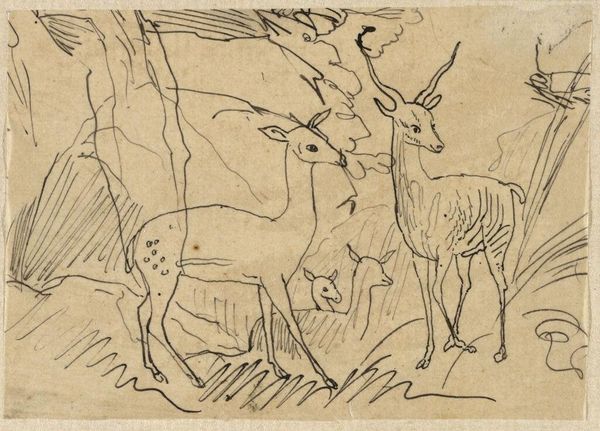

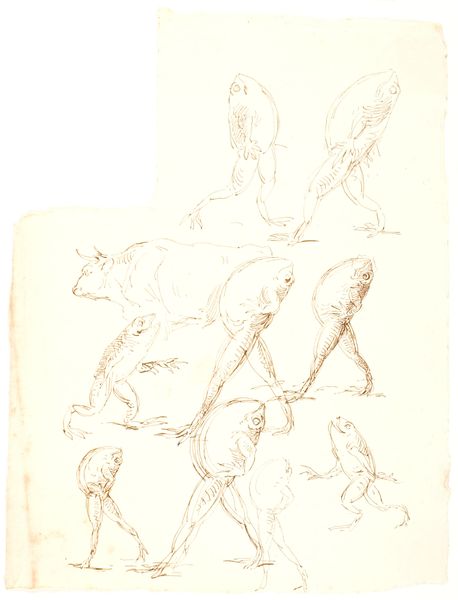

Curator: Welcome. We’re looking at “Schetsblad met dieren,” or "Sketch Sheet with Animals" by Johannes Tavenraat. It was made sometime between 1840 and 1880 and is held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The composition is very interesting. It looks like a page torn straight out of a personal sketchbook, full of quick studies of different animals—a duck, some sort of wading bird, a dog, and a deer. There is a playful energy here. Curator: The quick, almost dashed, lines definitely speak to the artist's process. Tavenraat seems to be capturing the essence of these animals with incredible efficiency using pen, ink and pencil. We’re seeing the working methods of a 19th century artist in action here. Editor: Yes, each creature has a very particular symbolism. The deer, for example, often represents gentleness, intuition, and connection to nature. And waterfowl often embody adaptability. Curator: While I appreciate those symbolic readings, I’m drawn to the more practical aspects: What paper did Tavenraat use? What sort of pens or pencils? The relative availability and cost of art supplies would’ve certainly impacted his choices here, not just in style, but the volume of production. These studies suggest a fluidity—did he use them for later works, or was the study its own end product? Editor: Fair point. I wonder too, about the cultural memory that is inherent in depicting these specific animals during that period. The 19th century saw an increased interest in the natural world, partly fueled by exploration and scientific advancement. Animals carried certain weighted connotations for the Victorian era that are echoed, however subtly, in their portrayal. Curator: Right, the rising availability of printed illustrations fueled a kind of mass engagement. The very act of sketching—replicating and recording the likeness of animals—implies a particular social relationship to the natural world in that period. This wasn’t merely a study of form; it's about the human relationship with our environment, visualized through affordable media. Editor: Absolutely, it's about looking at the layering of interpretations through visual cues. Thanks for the grounding influence there, reframing a bit through historical context. Curator: Anytime! By zooming in on his tools, it brings a much richer appreciation of context here—it reframes the consumption aspect from artistic training to that of accessible means of artistic representation. Editor: I'm leaving with a far more grounded view of both how an artist develops an intimate symbolic vocabulary while remaining acutely sensitive to materials within a cultural memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.