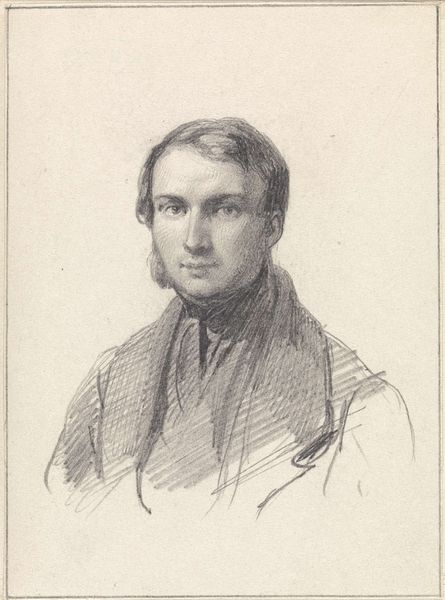

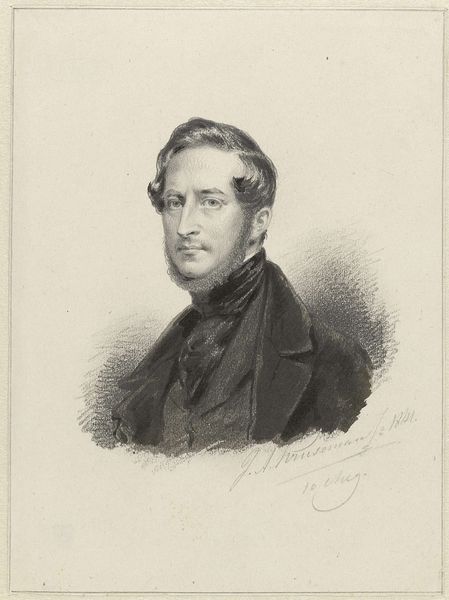

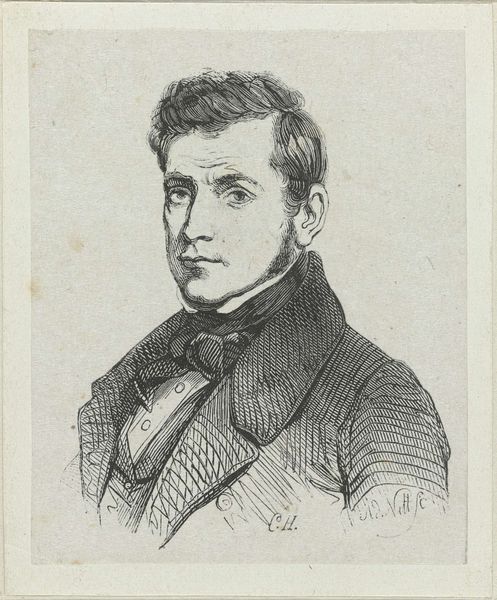

drawing, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink

#

romanticism

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Gijsbertus Craeyvanger's "Self-Portrait," an ink drawing created sometime between 1820 and 1860. The way he renders his own image has this almost theatrical, Romantic sensibility to it. What’s your take on it? Curator: It’s fascinating how the Romantics used portraiture, particularly self-portraiture, to construct a certain image. What is Craeyvanger trying to convey about himself, and how does that connect to the burgeoning Dutch national identity being formed in the first half of the 19th century? Is it about his status, his intellect, his 'Dutch-ness'? Editor: I suppose all of the above? It strikes me as different than, say, a Rembrandt self-portrait which feels more psychologically probing, warts and all. Curator: Precisely! Consider the institutional framework—the art academies and burgeoning museums—that dictated what was considered worthy of representation. Craeyvanger is participating in a dialogue with those institutions, projecting an image acceptable and even celebrated by them. How does this controlled representation serve a specific social or even political purpose? Editor: It’s almost like he's creating a brand for himself that fits into the romantic vision of the time! And selling it, so to speak, to these very important institutions! Curator: Yes! And consider too, how portraits were often commissioned. He may be advertising, projecting himself as worthy of patronage, of entry into the public eye, defining not just himself but his professional capabilities through visual means. Editor: I see what you mean. By aligning himself with Romantic ideals, he’s simultaneously gaining access to influential social and artistic circles and also constructing an artistic and public identity that's so...calculated! I initially didn’t appreciate that layer, I just saw it at face value! Curator: That tension – the personal versus the political, the 'authentic' versus the constructed – is central to understanding much 19th-century art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.