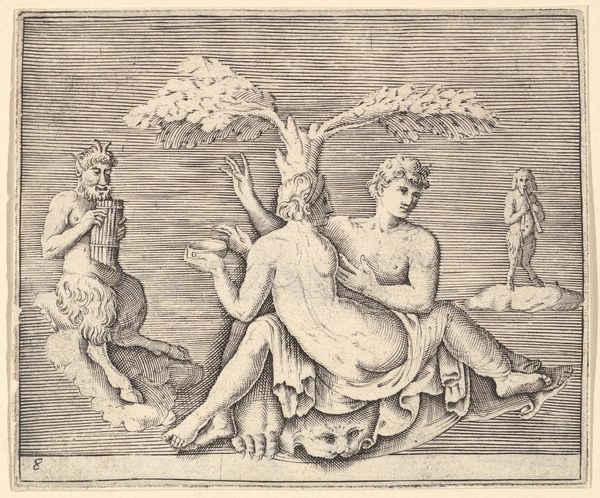

Head of Satyr and Three Figures, from "Ex Antiquis Cameorum et Gemmae Delineata/ Liber Secundus/et ab Enea Vico Parmen Incis" 1599 - 1622

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

classical-realism

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: plate: 3 7/16 x 4 7/8 in. (8.8 x 12.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Head of Satyr and Three Figures," an etching and engraving of anonymous authorship from the Renaissance, somewhere between 1599 and 1622, now residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My first impression is the cool, almost detached mood despite the erotic charge—the figures feel quite separate in their actions and expressions. Editor: It's interesting you use the word "detached." For me, it immediately conjures up an academic sensibility that often served political agendas. This isn’t some spontaneous act of passion. Instead, this controlled representation likely promotes idealized male forms and the justification of power. Curator: Ah, a Renaissance power play. Perhaps, but there's something else at work. The floating satyr head, a disruptive element. Satyrs, known for instinct and intoxication, were central figures in festivals. Is it commenting on our struggle to repress instinctive urges? Editor: Potentially, and that brings us to questions about authorship and intention. Consider who these images were created by, and for, and how those social positions informed their artmaking. Are they subverting or upholding power? And whose gaze is centered here? It matters that we confront those structures as viewers now. Curator: Agreed, acknowledging the complexities is vital. Consider also the vase; it serves as an almost blatant symbol. While seemingly inert, it represents transformation and potential, of controlled release, wouldn't you agree? The human figures act as a means to consider emotional themes with precision. Editor: But "precision" also flattens the emotional register, which is itself an act. While not rendering the figures naturalistically, a tool that would give way to Baroque, this choice normalizes their social roles as much as their anatomies. By referencing Classical forms, they also solidify claims to power in Early Modern Europe. Curator: Perhaps we’re looking at the Renaissance wrestling with its classical inheritance. Finding that there were two contrary ideas and not sure how to solve them, one solution would be repression by elevating them at the same time. What else can they do but strike a cool, academic, powerful pose? Editor: Absolutely, it’s a fascinating struggle indeed! We see, on the one hand, this reaching back for historical authority coupled with art making in its service. Recognizing and unpacking these choices are key to connecting with this print critically today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.