print, engraving

#

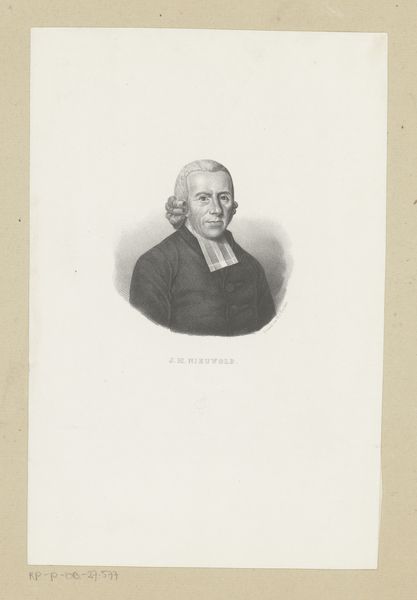

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find something undeniably arresting about this portrait. Before us we have “Portret van André Masséna, hertog van Rivoli, prins van Essling”, or "Portrait of André Masséna, Duke of Rivoli, Prince of Essling," crafted in 1798 by Heinrich Schmidt. It's an engraving. A sharp one, isn’t it? Editor: My immediate reaction is, he looks… severe. Intensely so! And that high collar certainly adds to the sense of constriction, doesn't it? Curator: Yes, there's an almost militant crispness to the rendering. It reminds me a little of idealized Roman portraiture that the neoclassicists of the day were aping, trying to connect current military leaders to the past of imperial Rome.. That blankness of the background makes the figure of Massena seem stark. What do you see? Editor: Well, I think about the political climate of the time. It's right after the French Revolution. Consider that this man was Napoleon's right-hand man; the artist presents an image that has historical, social, and gender implications. Power and authority! How does Schmidt negotiate this in relation to Masséna's character? It's intriguing! Curator: Schmidt is careful to not to betray, well, personality! He focuses instead on the accoutrements, which subtly suggest Masséna's status as an established officer. Editor: He certainly captures an image of the man in that particular moment, during the early Republic after all, how complicated can it be for Schmidt to negotiate the terms to depict Masséna in that way? What I mean is, who had control over that image? Curator: Those kind of visual controls were definitely happening around that period, I imagine the artist could not completely be at free will during that particular commission. Editor: Absolutely! The portrait is about an elite member, but the rendering in print format could indicate that they intended for this to have much wider distribution. To rally sentiment to their movement. And so the portrait exists somewhere between representation and propaganda, wouldn't you say? Curator: An excellent point. It speaks volumes about the way leaders are carefully, politically, branded—even then! Editor: Agreed. Reflecting on this portrait, I'm reminded how images are not just passive records but active agents in shaping perception and power dynamics. Curator: Indeed. And perhaps that’s the real magic of this… the subtle reminders of the constant shaping of our realities through representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.