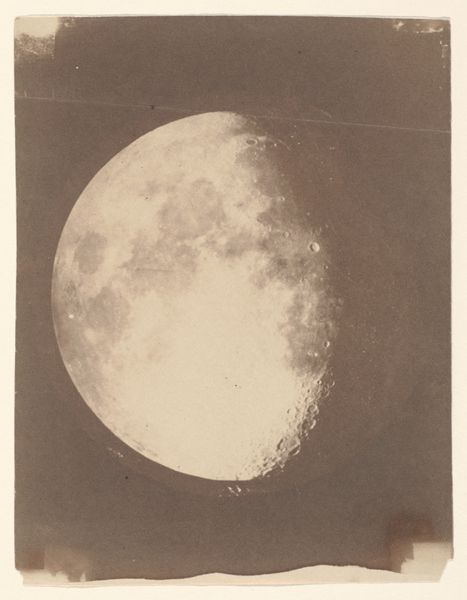

Dimensions: Sheet: 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. (21 × 15.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

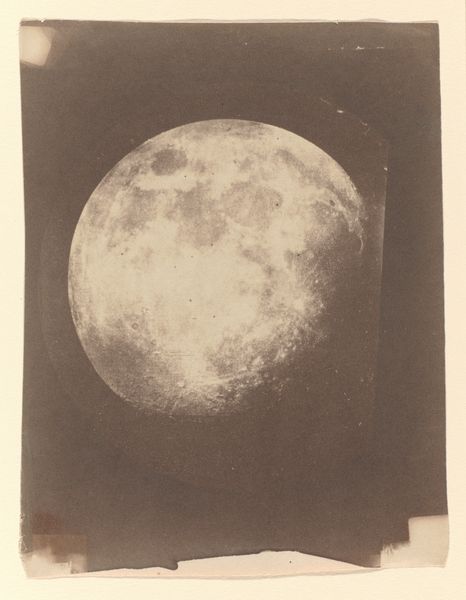

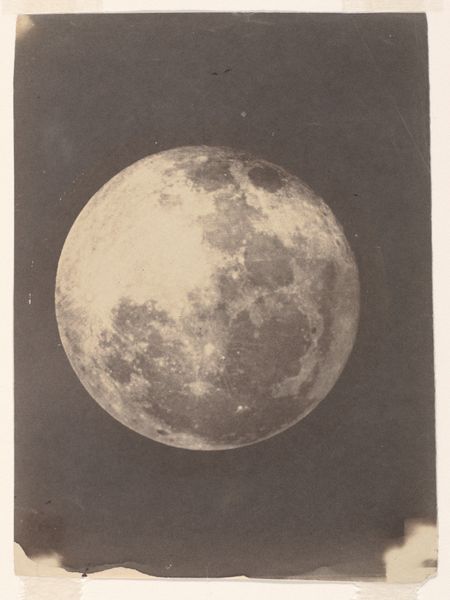

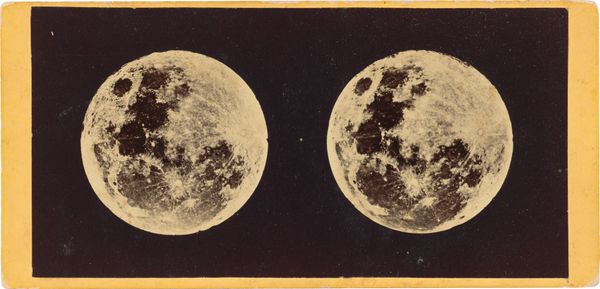

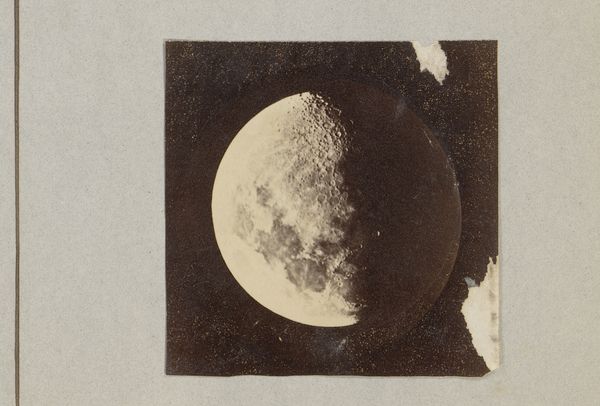

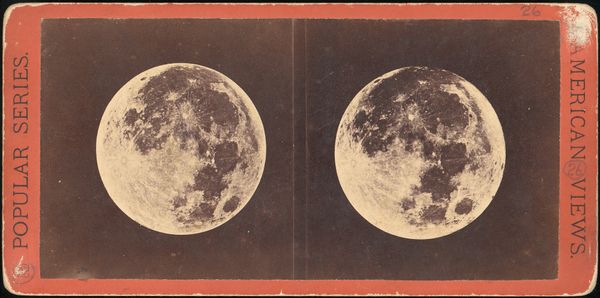

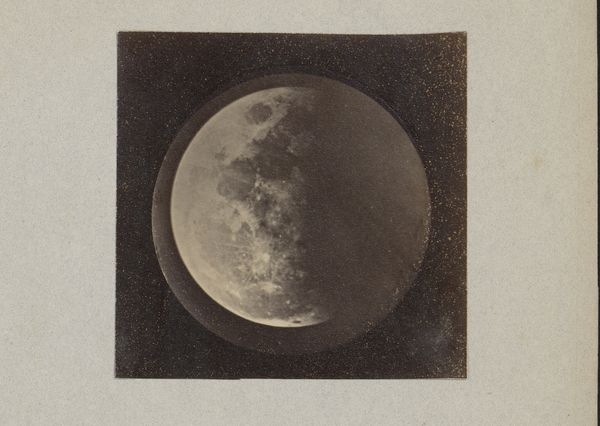

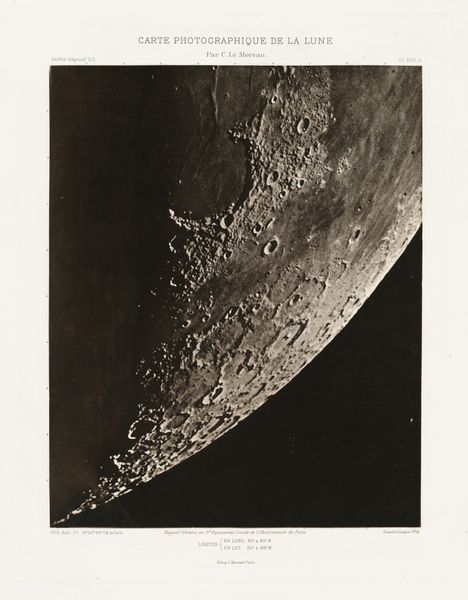

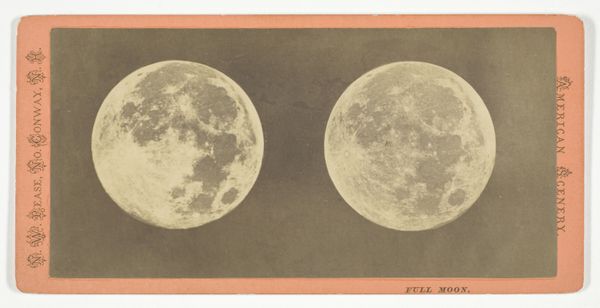

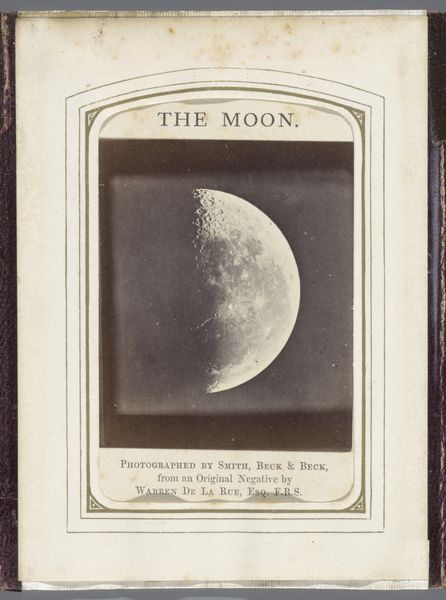

Curator: This striking image is called "The Moon," created by John Adams Whipple sometime between 1857 and 1860. Whipple was a pioneer in astronomical photography here in the United States. He used the daguerreotype and later the gelatin-silver print processes to create this evocative work. Editor: Wow, that moon looks so touchable! Almost like you could just peel it off the paper like a sticker. It has such depth, doesn't it? Like I can almost smell that cold, crisp lunar dust. Curator: Precisely! Consider the social context. Before this, depicting the moon with such accuracy was nearly impossible. Whipple’s photographs, alongside the advancements in telescope technology, captured public imagination and helped visualize the cosmos. Museums became key players in showcasing such groundbreaking imagery. Editor: Absolutely, I see what you mean. You know, thinking about it, there's a sort of romantic solitude here too. I mean, even today we can still see the same moon, more or less as he did, even with all of our screens and gadgets, and feel connected to a very, very lonely man taking pictures with very antiquated cameras and stuff, you know? And isn't that nuts?! Curator: I appreciate that deeply personal take, yes. But from a historical perspective, this was also about establishing credibility. The accuracy of such photographs helped scientists gather knowledge but it was also used in artistic circles who were looking to capture “truth.” Think of the relationship with realism in painting. Editor: Ah, interesting! Truth, right? It almost sounds like the same kind of promise modern selfies offer now – just a very antique, sepia-toned kind of truth. Is that really the truth of space and technology from that day or the truth of Whipple’s lonely pursuit? Curator: A vital consideration. "The Moon" reflects a burgeoning interest in scientific exploration but also in photography's capacity to portray not just what we see, but how we perceive. It is interesting how a quest for scientific accuracy intersected with a growing interest in capturing truth via photography at a particular moment in history. Editor: Well, the next time I look up at night, I’m going to feel a lot less lonely looking up into the cosmos, now that I am connected to a photograph of one lonely person photographing our natural satellite. Curator: It shows us how much looking outward can help us better understand ourselves and what it is to be human. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.