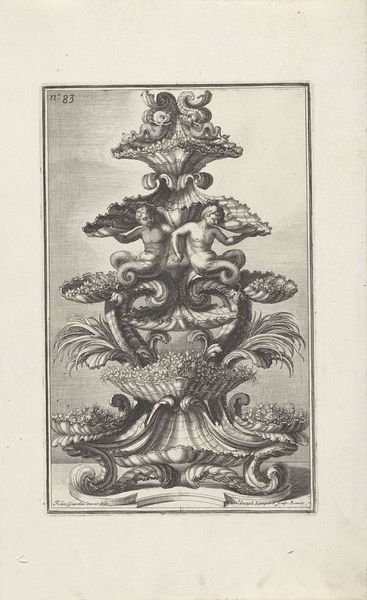

Ontwerp voor een tweearmige girandole van porselein en goud 1738 - 1749

0:00

0:00

gabrielhuquier

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

form

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 233 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Allow me to introduce you to a design sketch, "Ontwerp voor een tweearmige girandole van porselein en goud," dating from between 1738 and 1749. It’s attributed to Gabriel Huquier. Editor: Well, my immediate reaction is “exuberant!” All those swirling, florid lines – it's the very essence of Baroque extravagance distilled into a lighting fixture. I find it almost dizzying in its ornamentation. Curator: Dizzing is a good word for it! Huquier wasn’t just imagining form. Think about what this suggests: porcelain, itself a manufactured and controlled material, combined with gold... Luxury elevated, and light – literally enlightenment! – brought to bear in a tangible way. Editor: Precisely! It screams opulence, designed, no doubt, to illuminate some noble's parlor, a testament to their refined taste, and, perhaps more overtly, to their economic power. But I wonder about the labor involved. Someone, or many someones, had to translate this intricate design into a real, functioning object. Curator: It is compelling to reflect on the labor to execute the intricate details—from the porcelain flowers coiling around the dolphin motif, to the gold accents glinting in the candlelight. But consider its deeper essence. This design proposes a conversation, doesn’t it, between nature and artifice? Those twirling, organic lines... almost as though the piece grew into being, as though it's not designed but it rather bloomed. Editor: An excellent point! But let’s also consider the market that Huquier, as a printmaker, was courting. Prints like these weren't just idle doodles. They served as promotional material, showcasing artisans' capabilities to potential patrons. Each line an investment, not just a flourish. Curator: It brings up the question: Is art about elevating daily life or emphasizing social divides? Does this object truly celebrate both? Editor: A bit of both, perhaps. It is hard to not ponder where the work exists in between human aspiration and manufactured desire. It reminds us to think of these items not as isolated artworks but parts of much bigger networks of labor, patronage, and material consumption. Curator: Indeed. Pondering this small print unveils immense networks, human hands, fiery kilns, and gilded aspirations—lighting our way to further questioning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.