drawing, painting, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

regionalism

#

watercolor

#

realism

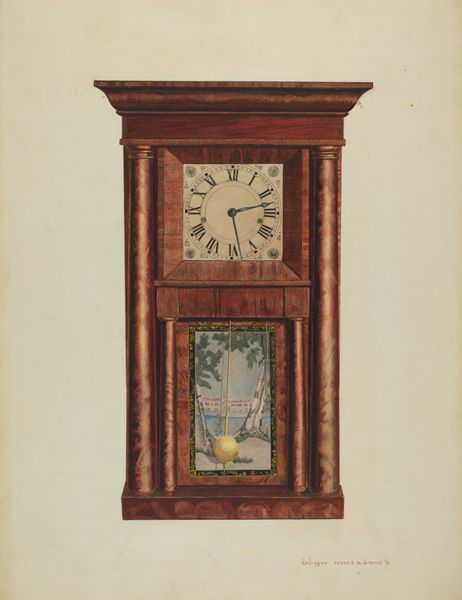

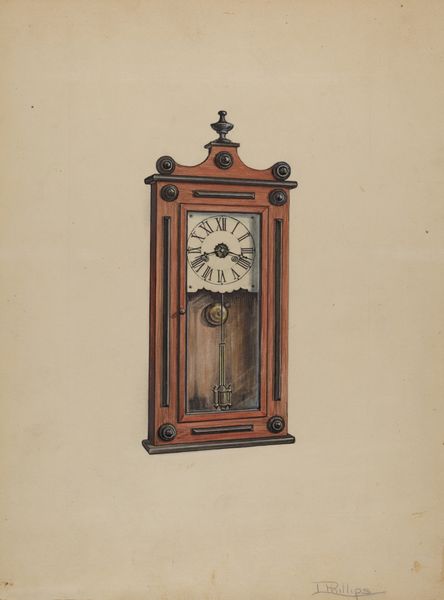

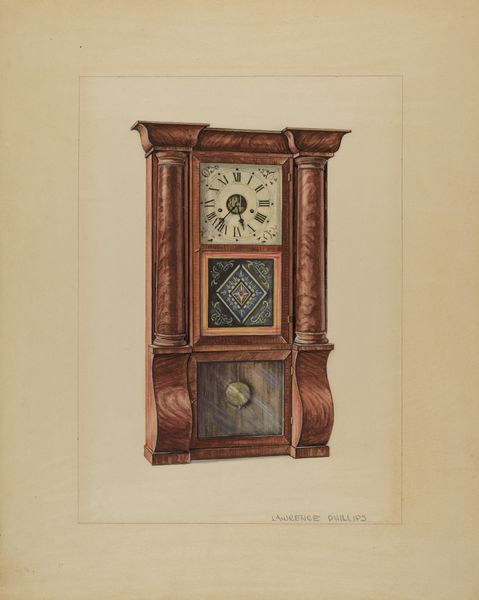

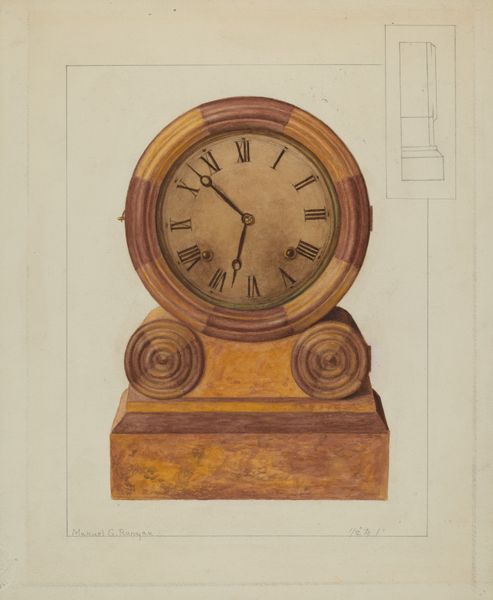

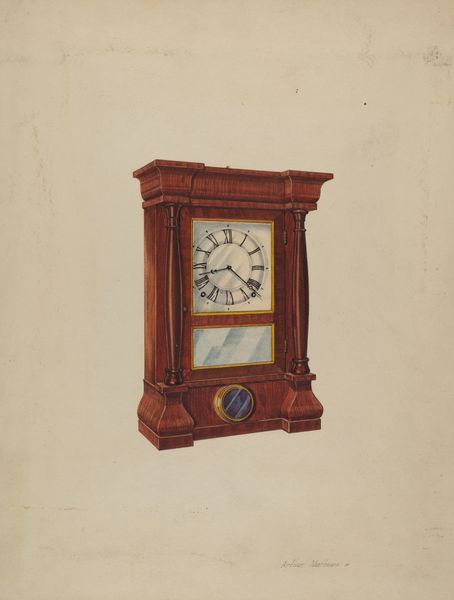

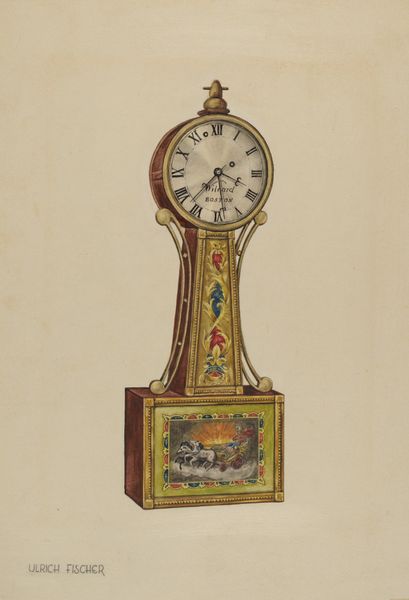

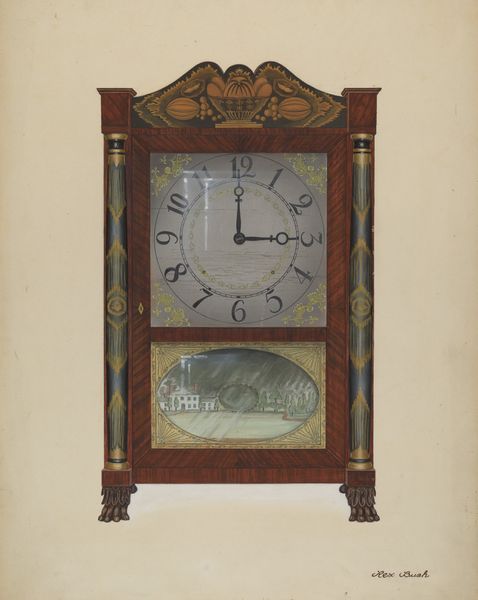

Dimensions: overall: 55.5 x 45.9 cm (21 7/8 x 18 1/16 in.) Original IAD Object: 26"high; dial 7 3/4"in diameter.

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Here we have John Koehl’s "Painted Clock" from 1940, rendered with watercolors and perhaps some drawing elements. I find it charming in a slightly unsettling way. What's your read on this curious depiction, particularly with regards to the choice of materials and subject? Curator: What strikes me is the tension between representation and function. It is not about a clock. The painting simulates a clock, inviting consideration of the labor of representation. Note the details in the wood grain – a trompe l’oeil challenging our understanding of "painting" as separate from craft or manufacture. This was painted during a period when notions of industrial production were dramatically affecting painting, right? Editor: Right, and the clock itself is broken or decayed, hinting at a breakdown perhaps. Is the landscape element significant? Curator: Absolutely. The incorporation of a landscape, visible through what would be the clock's pendulum space, transforms the entire piece. This blending challenges traditional hierarchies—fine art landscape versus the utilitarian object of the clock. Think of the labor embedded in maintaining landscapes during this time, the class divisions apparent in the image. The production of the scene through human toil and care. Does it transform how we understand craft? Editor: So, instead of seeing a still-life, we should consider how Koehl blurred those established distinctions between artistic categories and physical labor, and its effect on consumption during the era. It is compelling when considered in this way. Curator: Precisely. This painting, using accessible materials such as watercolor, engages with then emerging material conditions by obscuring boundaries to pose fundamental questions about art’s place and function in society. Editor: That provides a fresh perspective, looking at not just what is painted, but how its construction relates to the surrounding societal landscape. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.