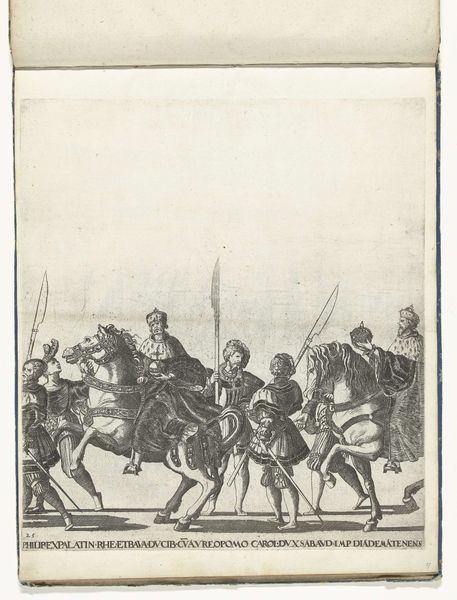

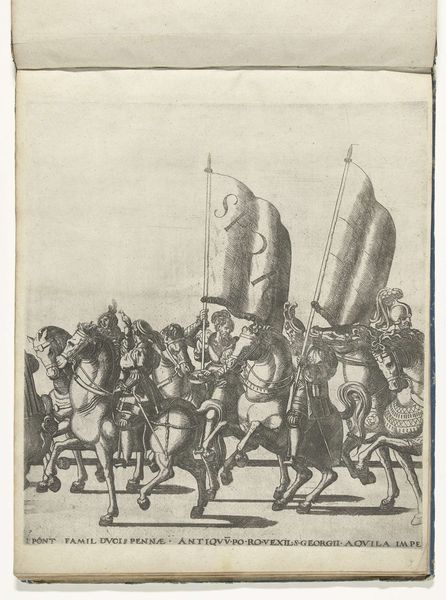

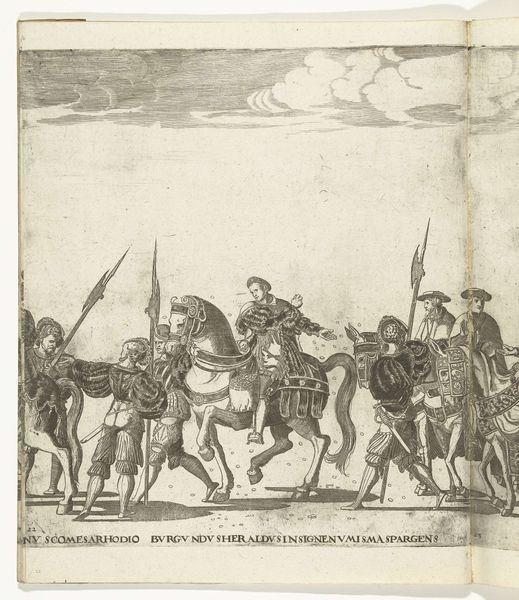

Bonifatius IV Paleologo, markgraaf van Monferrato, met de keizerlijke scepter en Francesco Maria della Rovere, hertog van Urbino, met het keizerlijk zwaard, plaat 24 Possibly 1530 - 1620

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

ink

#

group-portraits

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 300 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

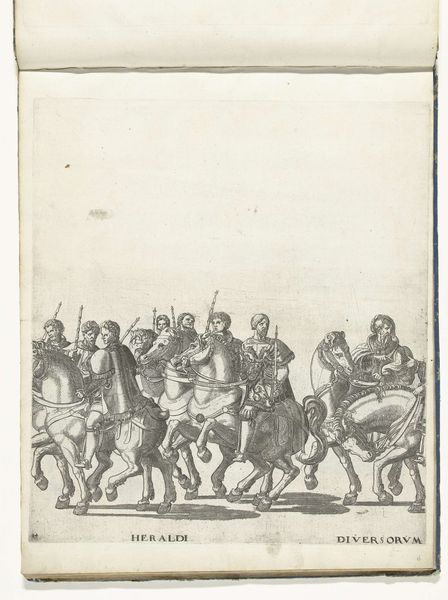

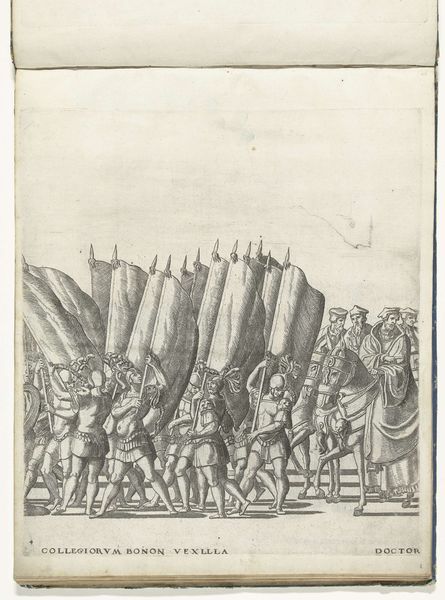

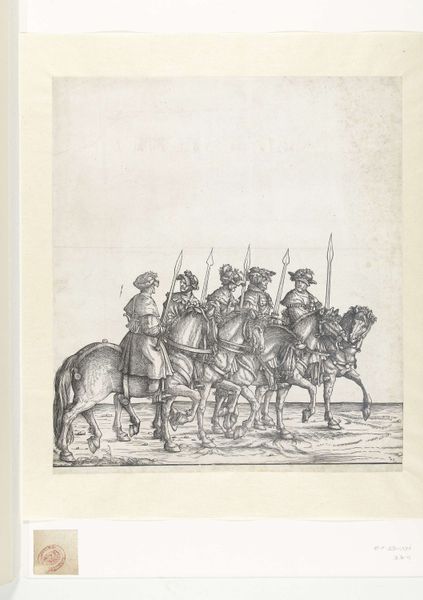

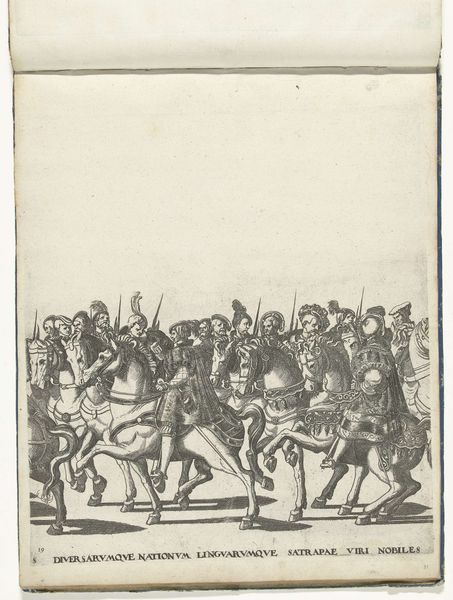

Editor: So, this is Nicolaas Hogenberg's engraving, "Bonifatius IV Paleologo, markgraaf van Monferrato, met de keizerlijke scepter en Francesco Maria della Rovere, hertog van Urbino, met het keizerlijk zwaard," possibly made between 1530 and 1620. It's a pen and ink print… there's a lot of detail packed in here! What strikes me most is the contrast between the figures on horseback and those walking; what do you see? Curator: What I find interesting is considering this piece as an object, reflecting labor and production. Think about the artist, Hogenberg, meticulously using a pen to create this print. It's a repeatable image, meant for wider circulation than, say, a unique painting. Editor: Right, so it is intended as more widely available? Does this suggest a democratization of portraiture? Curator: To a degree, yes, compared to unique painted portraits reserved for the elite. But we need to consider who had access to these prints. They weren't cheap. Think about the materiality of ink and paper. Who was consuming these images, and what did their consumption say about their own social status and aspirations? Is it purely documentary, or aspirational propaganda? Editor: That’s a good point! It still suggests more opportunity to be viewed, and also a specific desire of those depicted to project and disseminate their image, possibly even their own version of the story. Curator: Exactly! The means of production themselves encode power relationships. The very act of creating and circulating these prints tells us about the social hierarchies. This connects with similar historical portraiture - think about the costuming in the portrait itself, reflecting social rank. We are then forced to examine labor practices, value assigned to skills such as printmaking, as opposed to paintings. Editor: I hadn’t really thought about the economic aspect of creating and disseminating these kinds of portraits. It gives you a whole new perspective. Curator: It reframes how we look at even something as seemingly straightforward as a historical portrait. Focusing on production and materials brings the social and economic context into sharper focus.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.