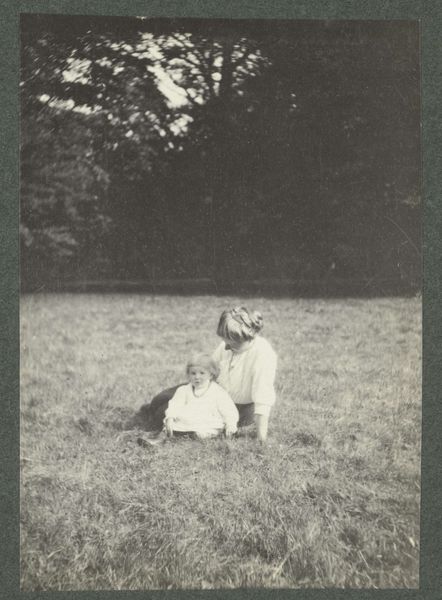

Tine Kleiterp-Vermeulen en haar kinderen Klaas en Tiny in een tuin in Pangka op Java 1921

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

garden

#

landscape

#

photography

#

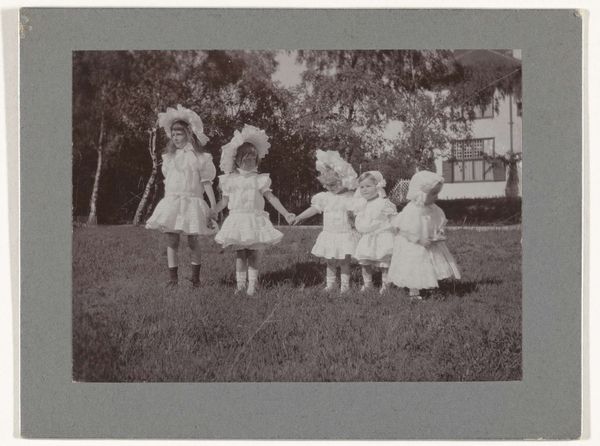

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 59 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There's something wonderfully serene about this image. It’s titled "Tine Kleiterp-Vermeulen en haar kinderen Klaas en Tiny in een tuin in Pangka op Java," a gelatin-silver print taken in 1921. Immediately, I’m drawn to the stillness of the scene, that filtered light. Does it strike you as peaceful, too? Editor: Yes, but there’s also an undercurrent there. Colonial Java, 1921… This isn't just a serene snapshot of motherhood; it's a portrait of Dutch presence, of privilege amidst the complexities of colonialism. The “peaceful garden” is inevitably laden with the socio-political realities of the time. Curator: Ah, always bringing me back down to earth! I was busy admiring the composition, the way the light falls on the children's faces. But yes, of course, there's that whole other layer. A gelatin-silver print… you imagine this moment, perfectly posed, as a relic of a very particular lifestyle. Did photography play a big role at that time, as an element of constructing these representations? Editor: Absolutely. Photography, during that period, was complicit in constructing and maintaining colonial power dynamics. These kinds of idyllic family portraits would circulate back home, painting a very particular and often skewed picture of life in the colonies—one of effortless ease and superiority. This is about reinforcing the idea of the colonizer’s place in the world. I mean, look at that perfectly maintained garden! Who is taking care of that garden, right? Curator: It feels distant and precious in that old style of photograph, so clear, you get an impression of realness but you are also aware that reality can be deceiving in the lens. Yet, there's an undeniable intimacy there, a feeling of connection between the mother and her children in the quiet garden setting. It speaks of human bonds beyond historical analysis, don’t you think? Editor: Perhaps, but even that “intimacy” has to be viewed through the lens of power. Who gets to have those quiet moments, in that kind of setting? Whose labor made it possible? I'm not saying there's no genuine affection here, but we can’t extract it from its context. These portraits functioned as carefully crafted displays of colonial success. Curator: A moment captured, forever pinned to the fabric of complex socio-political realities. That’s something. Thanks for untangling that one for me, again! Editor: Of course! That’s the power of seeing art through a broader historical and theoretical perspective—it's about unearthing these uncomfortable truths and widening our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.