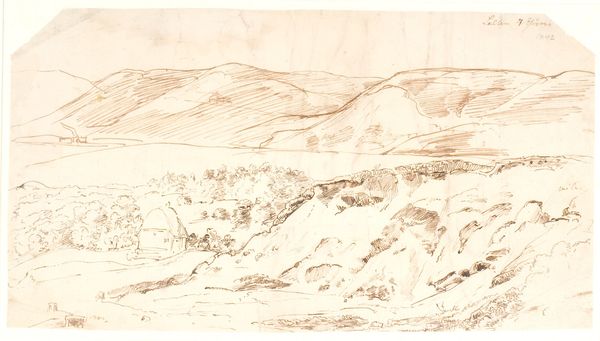

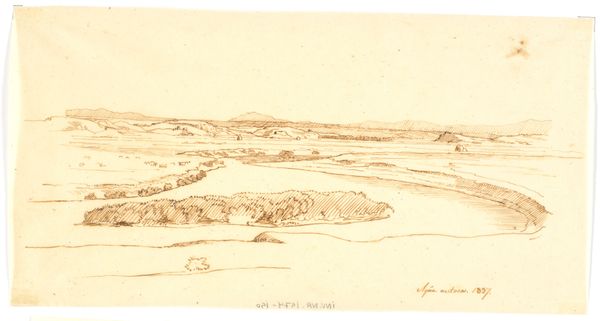

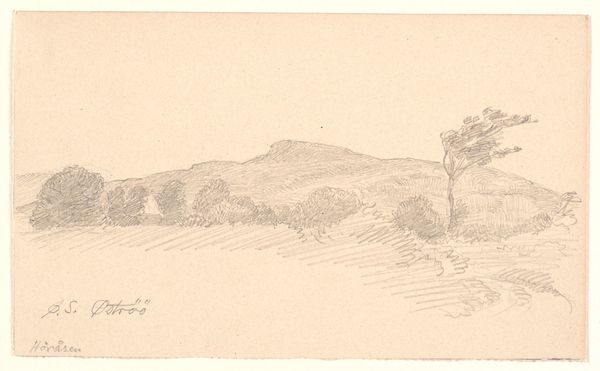

drawing, plein-air, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

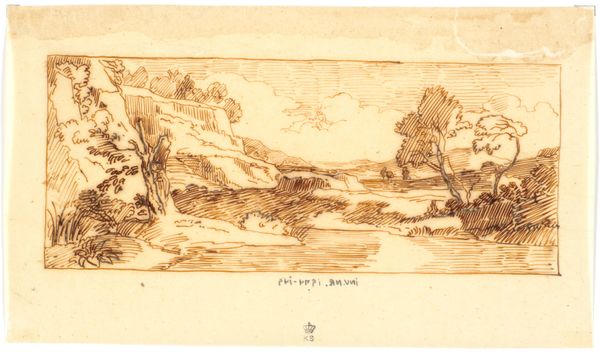

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

Dimensions: 115 mm (height) x 220 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This ink and paper drawing is entitled "vicino di Torre del Quinto," created in 1837 by Martinus Rørbye. Editor: My first impression is the incredible sense of depth he achieves with such delicate lines. It’s vast and feels open, almost inviting you to step into the landscape. Curator: Rørbye was known for his plein-air sketches. He made them while traveling; in this case around Rome. You can almost picture him seated on a hillside, meticulously capturing the essence of the Italian countryside. He would later utilize this on-location work for his paintings. Editor: It speaks to a very specific moment in the 19th century when artists began interacting differently with landscapes and what it meant to study it. The mark-making here seems exploratory, even experimental in its relationship to the romantic notion of being among untouched nature. How do you think that location—outside the studio, directly observing the landscape—impacted his artistic choices? Curator: Working outdoors forces you to consider time, light, and material constraints in unique ways. He needed portable materials. Rørbye utilizes the fluidity of ink to describe different surfaces and textures with efficient and economical means. We are not far removed from seeing landscape utilized primarily in service of history painting, and in these drawings Rørbye gives nature a life of its own. Editor: Absolutely. And the very act of choosing to depict a relatively humble landscape, rather than a grand historical scene, hints at shifting values. Where are we putting our labor as a society? And how are the tools of drawing mediating our encounters with nature? Are they emphasizing our control and authority or encouraging openness? Curator: It highlights a shift in artistic production, making work directly responsive to the immediate world. These landscapes weren’t just backgrounds, but studies of social and natural histories. They are not just about visual likeness; rather they are material acts and records of the encounter between the artist and his subject. Editor: I completely agree. Considering this work within the broader context of 19th-century art reminds us that these quiet scenes were actually participating in very active artistic, cultural, and intellectual movements. Curator: This examination reminds us how a landscape transcends its representation, embodying the spirit of a changing world and challenging our own modes of production and art-making. Editor: I now see it as a portal to the past but also to a more embodied practice that resonates with our current moment, encouraging viewers to seek meaning within materiality and their own relationship to place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.