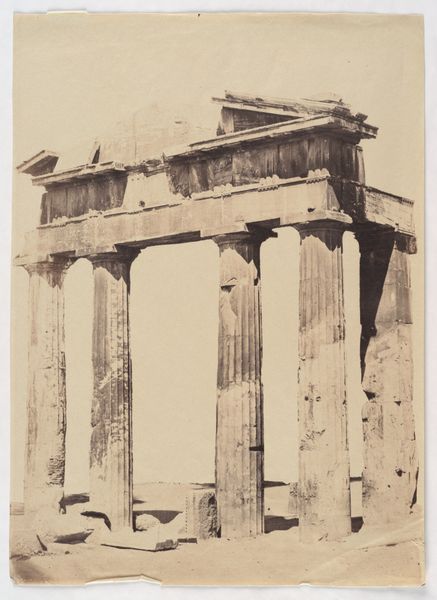

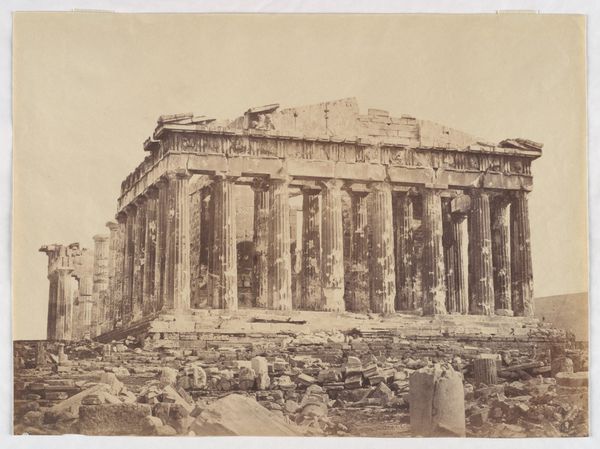

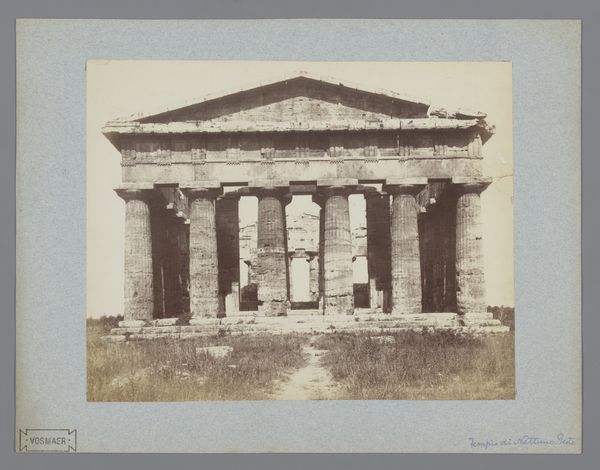

![[Acropolis, Athens, Greece] by James Robertson](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzc3NDIyMDA4LWQ5ZmYtNDFiNi05NTJlLTc2ZDUyYmNlNTFhMC83NzQyMjAwOC1kOWZmLTQxYjYtOTUyZS03NmQ1MmJjZTUxYTBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

daguerreotype, photography

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: Approx. 11 x 15

Copyright: Public Domain

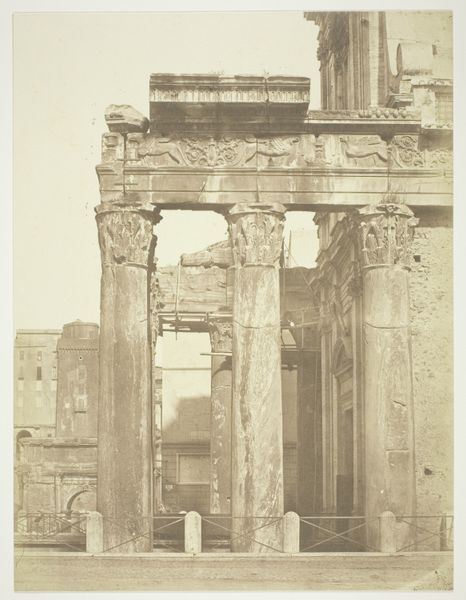

Editor: This is a daguerreotype by James Robertson, taken between 1850 and 1855, capturing the Acropolis in Athens. It feels monumental and somehow desolate. What are your initial thoughts? Curator: Well, focusing on materiality, it’s crucial to understand the daguerreotype as an object, a copper plate made photosensitive through a chemical process, developed with mercury vapor. In the mid-19th century, capturing an image of this scale and detail demanded immense skill and specialized labor. Think of the journey to Athens, the transport of equipment, the processing – a global network fueled by colonial power dynamics to document these sites. Editor: That’s fascinating. It completely changes how I see it. So, it's not just about the artistry but about the means to even create this image. The socio-economic conditions become part of the picture itself, literally! Curator: Precisely! Consider the materials themselves: Where did the silver come from? Who mined it? And who processed it? These "details" expose the networks of labor, the exploitation embedded within the act of documentation. It asks us to question whose vision this truly represents – the photographer, the patron, or the system that enabled its production. Editor: So the decay evident in the Acropolis' stones is mirrored by, maybe even inseparable from, the historical "decay" of those who made its imaging possible. Is it possible to look past these colonial-era questions when approaching artwork like this? Curator: No, not if we're engaging critically with the object. Understanding these networks is not about assigning blame, but recognizing the interconnectedness of history, labor, and artistic creation. Editor: I guess it's a constant negotiation between admiring the final product and acknowledging the context that made it possible. Curator: Absolutely, a materialist approach to art acknowledges that tension and seeks to reveal the hidden stories embedded within the materials themselves. We shift the focus from idealized beauty to the complex, often troubling, realities of production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.