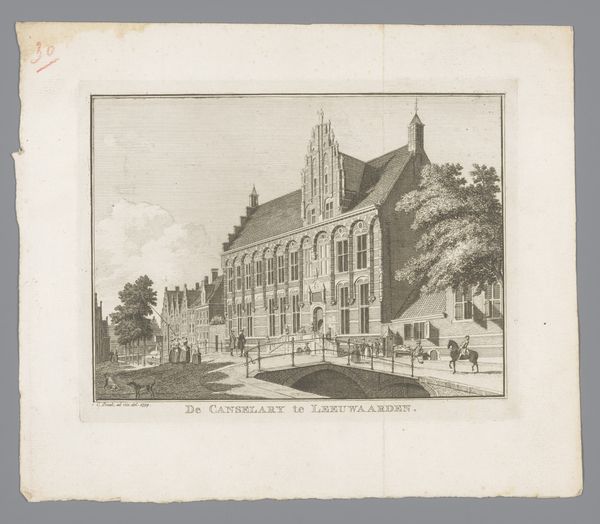

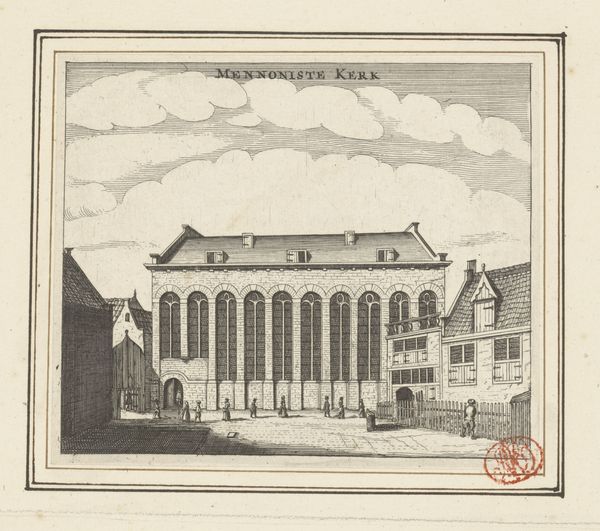

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

#

realism

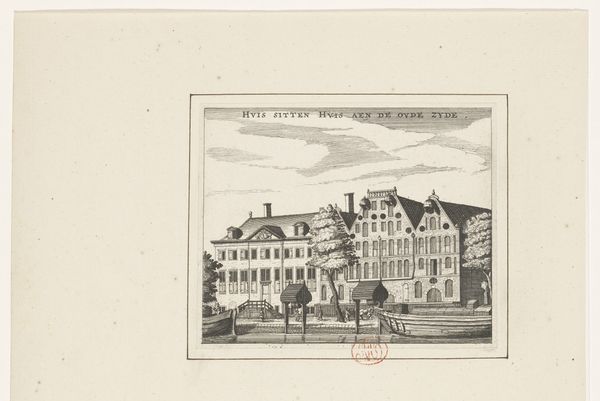

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s take a closer look at this etching, "Gezicht op buitenhuis Rust en Werk," or "View of the country house Rust en Werk" by Adriaan Willem Weissman. It likely dates between 1850 and 1887. What strikes you first? Editor: It feels very formal and composed, almost like a portrait of a building rather than a landscape. There’s a real emphasis on the architecture. It's precise. Curator: Exactly. Look at the clear lines defining the brickwork and windowpanes. Consider the labor involved in such precise work. Weissman likely created numerous preparatory drawings to achieve this level of detail in the etching. This print, therefore, wasn't just aesthetic, but a means to document and disseminate architectural designs of the time. Etchings like this circulated among builders, clients, and even other architects. Editor: It also speaks to the burgeoning sense of national pride and the rising middle class, right? A print like this would have helped communicate a particular image of Dutch prosperity and order. Displaying such a print communicated one’s aspirations, mirroring, in a sense, the actual ‘Rust en Werk’ or 'Rest and Work' the building represented. Did the gallery exhibit works like this often? Curator: Certainly. Public taste increasingly demanded depictions of both national progress and reassuring images of domestic life. The artist, therefore, positioned himself carefully. By depicting scenes that fulfilled those criteria, he created something highly marketable using easily reproduced etching processes. We see then an intentional appeal to those burgeoning sensibilities and a middle class market. Editor: It makes me wonder, who actually *lived* in Rust en Werk, and what stories are behind the bricks. Weissman, with his choice of etching, also nods to the grand tradition of Dutch Golden Age masters. But do you see any sense of criticism in this almost clinical presentation? It does leave me rather cold. Curator: Perhaps cold because the mechanical reproductive process doesn’t have the trace of the individual hand? While on its surface it offers an image of stability, perhaps it hints at a tension inherent in the pursuit of both ‘rest’ and ‘work,’ and their inherent social connotations. Editor: So much history locked within the lines of an etching! It's amazing. Curator: Indeed. Each mark is a record not just of artistry but of a whole network of social, economic, and aesthetic forces at play in the late 19th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.