drawing, pencil

#

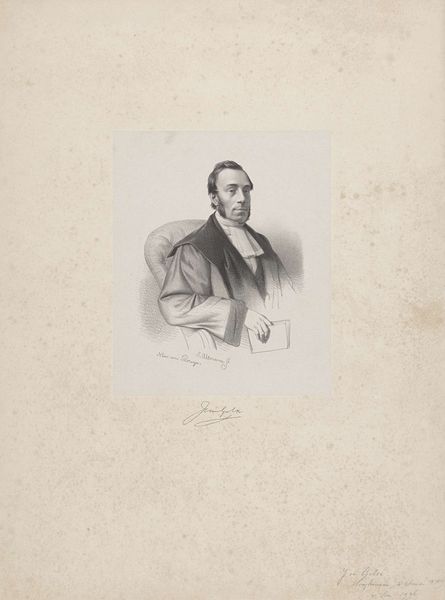

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

pencil work

#

realism

Dimensions: height 580 mm, width 432 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

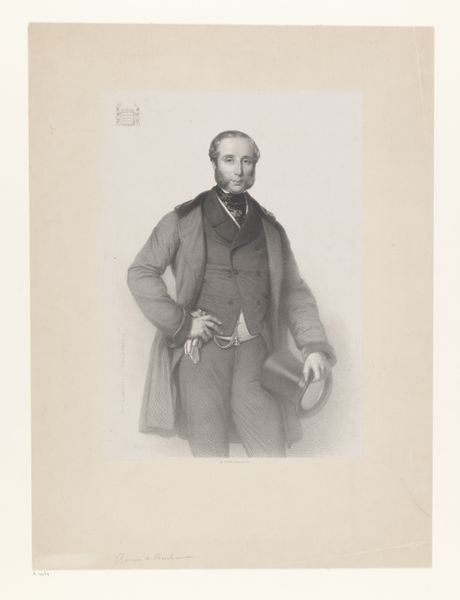

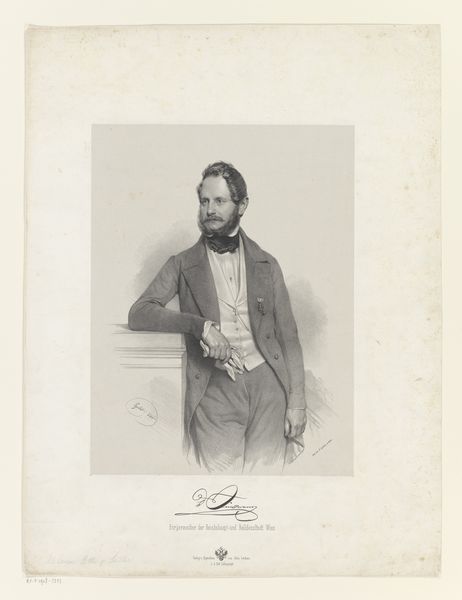

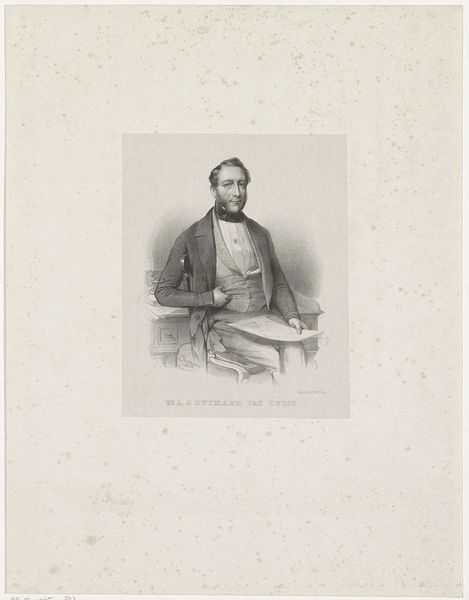

Curator: The portrait we’re viewing is entitled “Portret van Theodor Friedrich von Hornbostel,” crafted in 1849 by Franz Eybl. It’s a striking pencil drawing currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a real intensity in his gaze. The monochromatic palette enhances the stern impression, lending a sense of quiet authority. The way the light falls, almost sculptural, draws your eye into the depth. Curator: Indeed. Consider the social context of portraiture in the 19th century, it was primarily for the wealthy and served as a demonstration of status. Here, Von Hornbostel, leaning casually with a jacket draped, portrays an air of accessible power. But it begs the question, who was he? What did it mean for Eybl, a popular portraitist of the time, to capture this image? Editor: The simplicity of the pencil – readily available, relatively inexpensive – contrasts with the luxury being portrayed. Look at the textures: the meticulously rendered fabric of his suit, the stubble of his beard. There's a dedication to capturing reality through accessible means. What does the artist's process say about broader society? Were simple pencils as available as one thinks or were they made and consumed by a limited percentage of the public at the time? Curator: Interesting. That prompts us to consider the socio-economic conditions of artistic production during that era. Was it simply about individual talent, or were other forces at play that determined what kind of materials were available and who could even afford them? Think also of romanticism and its interest in realism at the time, something that is so carefully displayed here. Editor: Absolutely. It all feeds into this interplay between materiality, production, and social representation. The labor of the artist, the accessibility of the tools, and the wealth represented – they all intertwine, shaping how we read the work and how it participates in shaping ideas around labour, value, and production at that moment. Curator: Considering all these angles enriches the work far beyond simply being a portrait, as it engages with ideas concerning class, access and image production. Editor: Exactly. A simple pencil drawing can tell complex tales.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.