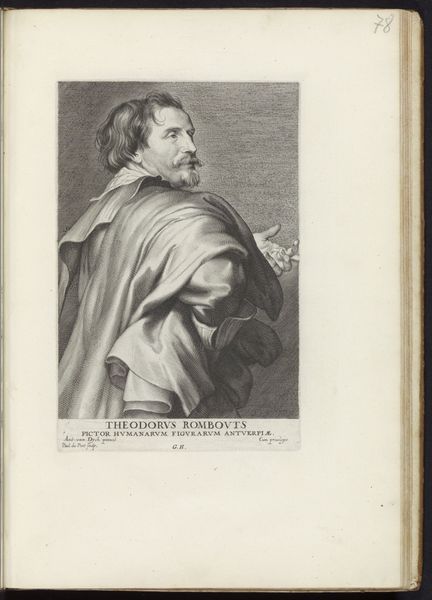

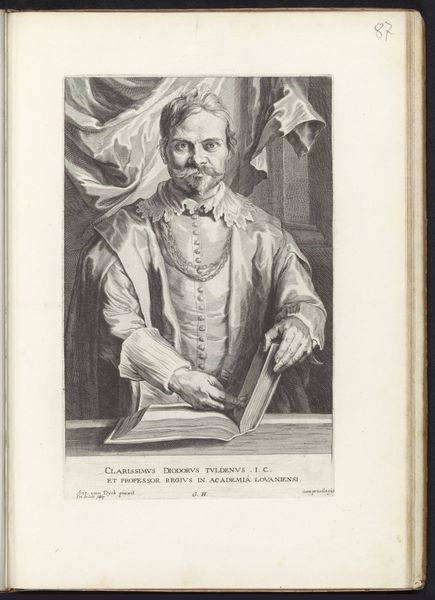

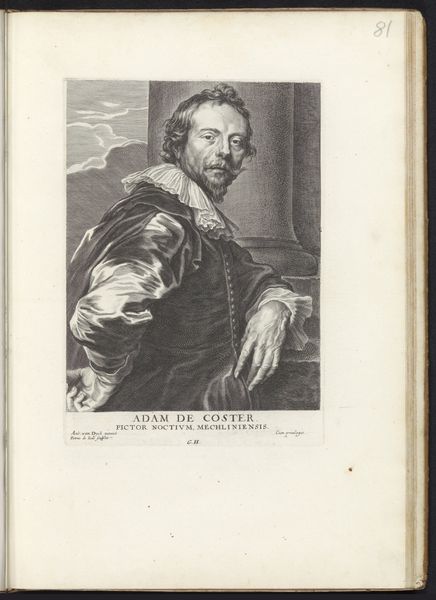

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Isn't it wonderful to pause and consider who gets remembered, immortalized in these halls? Here we have an engraving, likely from between 1630 and 1646, titled *Portret van de kunstenaar Jacques Jordaens,* or Portrait of the Artist Jacques Jordaens, now held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has an arresting quality, almost melancholic. The tight ruff around the neck and the hand held so deliberately over his chest, it feels very... staged, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: It certainly speaks to the conventions of the time. These prints served as crucial tools in shaping an artist's reputation, circulating their image and asserting their importance within artistic circles. It's believed to be by Pieter de Jode the Younger. Editor: De Jode captured something, though. There's a weariness around the eyes, a hint of introspection that transcends the formal pose. Is it me or can you sense also just a subtle challenge? The hand isn't just resting; it's… possessive. Curator: An intriguing observation! The gesture could be interpreted as both a sign of humility—common in Baroque portraiture—and a quiet assertion of artistic identity. This portrait becomes more compelling once you realize that Jordaens himself was one of the leading Baroque painters in Antwerp. Editor: Oh! A bit of self-promotion masquerading as humility, perhaps? Curator: Well, perhaps it was to signal Jordaens's role in a burgeoning art market of the Dutch Golden Age. These images weren't just about memorializing a face; they were also part of the construction of artistic celebrity. Editor: Makes you wonder what Jordaens thought of this portrayal of himself. If he saw it as a true reflection, a caricature, or just another piece of marketing. He must have at least been partly conscious of the fact. Did he find it as deeply… searching… as I do? Curator: And how many viewers, throughout the years, saw it as an entry point to a dialogue, not just with the man, but also with the world of art-making itself. These portraits give access to that artist and that world that otherwise may not exist. Editor: True. This simple print ends up doing far more work than its delicate lines would suggest, it’s lovely in its complexities!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.