Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 116 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

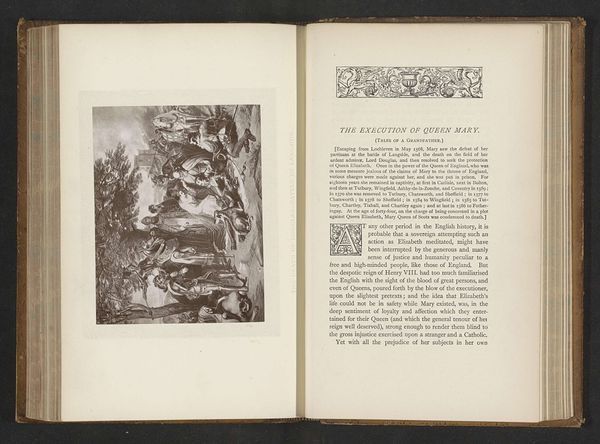

Curator: This print, "Charles the first at Naseby," housed here at the Rijksmuseum, pulls us into a tumultuous moment in history. While the artist remains anonymous, we know it dates from before 1885. The combination of etching and engraving techniques lends it a striking quality. What's your immediate response to it? Editor: Chaos. That's the first word that comes to mind. There's an overwhelming sense of disorder. Look at the mass of figures, the tumbling bodies, and the way the smoke billows. It suggests a breakdown of established order, not just on the battlefield, but perhaps within the social and political fabric itself. Curator: Precisely. The Battle of Naseby was a pivotal clash in the English Civil War, wasn’t it? Examining the figures, the symbol of Charles I is central. Even fallen, the focus returns to his character, his choices that led him to this end. Do you agree the visual focus reinforces him even as he loses the conflict? Editor: Absolutely. Although Charles is physically overwhelmed, the composition directs our eye to him, even in defeat. We're forced to reckon with his presence. We have to consider who benefitted from idealizing his image in failure. It invites discussion on what romanticism seeks to achieve as an artistic tendency, rather than accurately represent historical reality. Curator: Consider also the Romantic and Academic styles coming together in this narrative. We witness not just an event, but an interpretation charged with drama and emotion. The choice of printmaking also allowed this image and the messages behind it to reach a wider audience, wasn't it? Editor: That's a crucial point. Reproducibility is a powerful tool for disseminating narratives and shaping collective memory. It raises questions about the intentions behind creating and circulating such an image. It encourages questioning power structures. Curator: Indeed, considering the visual language and its broader context enriches our understanding. The print preserves not just an event, but also interpretations. Editor: The image feels like an argument, doesn’t it? An argument frozen in time and endlessly replayed. And like all arguments, it's worth examining the motivations behind it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.