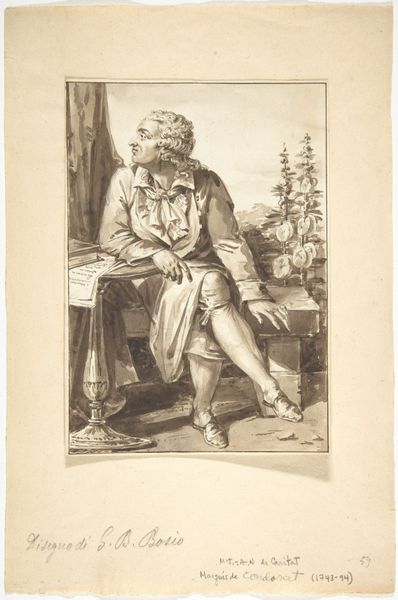

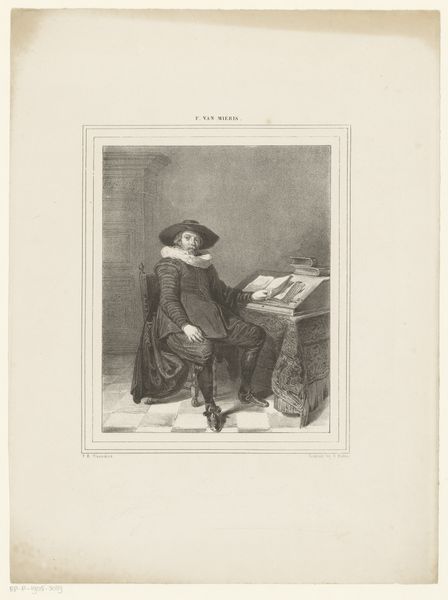

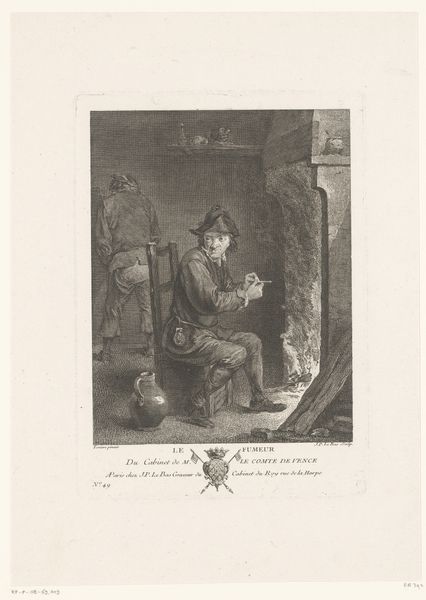

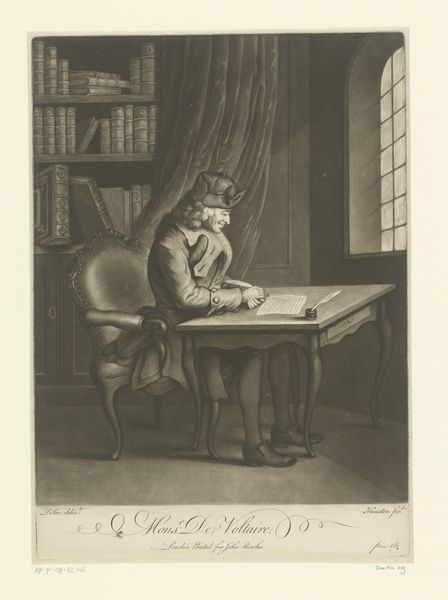

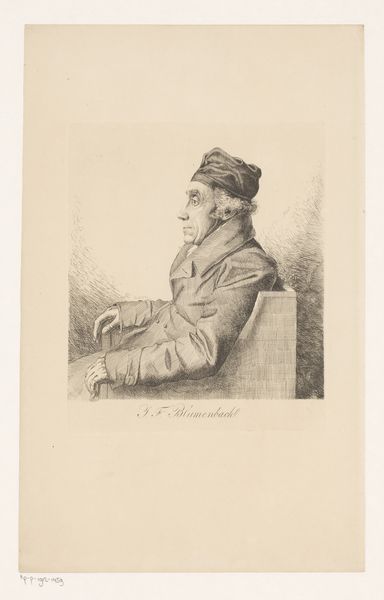

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 379 mm, width 360 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

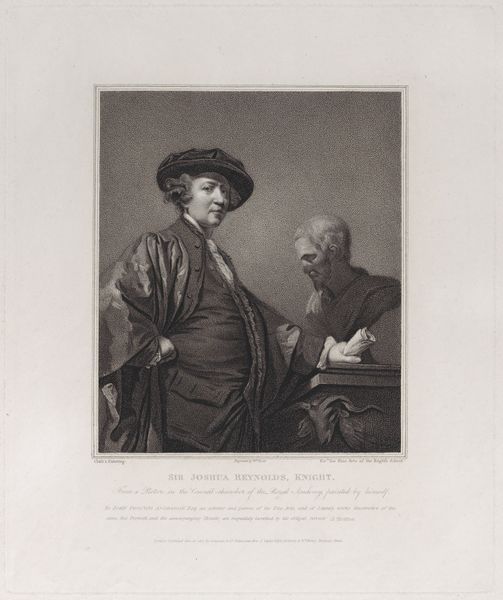

Curator: Welcome! We are standing before Jean Daullé's "Portret van Jean Vincent Capronnier de Gauffecourt", an engraving crafted in 1754, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first thoughts? Editor: Intricate, obviously! And sort of... knowing? There's something clever in that raised finger and the slightly smug expression. Like he knows a secret, or perhaps he’s about to deliver a zinger of a bon mot. It's as if he's caught mid-thought, isn't it? Curator: Indeed. This is a wonderful example of portraiture engaging with history painting, a prominent style of the Baroque era. It provides insight into how influential people wanted to be perceived, almost as living relics or characters of importance for future audiences. Editor: Ah, yes. The theatrical draping of his robe! And those ridiculously frilly cuffs! But there's also a sort of intellectual air, or maybe he has indigestion? It's an odd mix of swagger and… something less majestic. A well-dressed thinker. Curator: Thinkers needed their branding as much as anybody. We are viewing here both artistic and historical intentions; we see not just Capronnier de Gauffecourt the individual, but Capronnier de Gauffecourt the cultivated, influential man of his time. Daulle makes calculated decisions of what to focus on to construct a particular narrative, one the sitter commissioned himself! Editor: The scene feels very staged—every book, inkwell and textile placed "just so," carefully, almost artificially composed. One might question if they read the book, or know what to do with the quill and ink in their hands. Almost cartoonish like a prop designed to reinforce a persona or status! It almost looks too perfect, or too neat? Curator: Precisely. As a museum object, Daulle's print reveals a moment in 1754 where history, personal image-making and social forces intertwined with lasting visual effects for both us and the era's patrons. The "Baroque" style, in the portrayal of wealth and finery in dress or domestic setting, served a crucial role in upholding hierarchy and class and social dynamics. Editor: And I wonder how accurate or idealized it is? Does the Latin inscription have something to do with the overall intent or message, too? "Latus in praesens animus quod ultra est..." — which roughly translates, doesn’t it, to “A mind at ease with the present hates whatever lies beyond?” Is that the key to his serenity? Curator: An interesting point for reflection: in revisiting the art piece with new critical perspectives or contexts, what are our readings for Capronnier and Daulle's intents? Does it reveal or conceal? Does art need to tell "the truth", or capture another objective? Or something else completely? Editor: Questions for today. Food for thought indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.