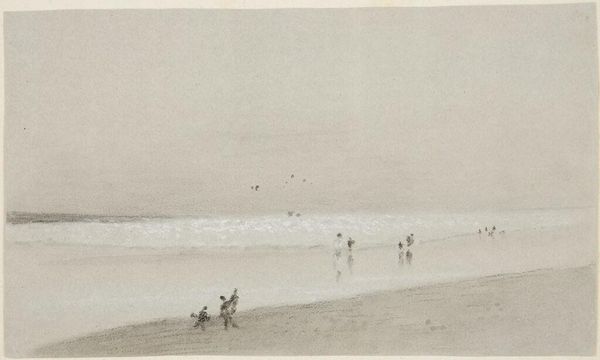

Twee personen bij een boot op het strand, vermoedelijk ter hoogte van Le Moulleau bij Arcachon 1897

0:00

0:00

delizy

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This photograph, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, is entitled "Twee personen bij een boot op het strand, vermoedelijk ter hoogte van Le Moulleau bij Arcachon," or "Two People by a Boat on the Beach, presumably near Le Moulleau at Arcachon," and was taken around 1897. Editor: It’s melancholic. The monochromatic sepia tones contribute to this washed-out feeling, like a memory fading, fitting for such an aged photo. The low horizon and choppy water evokes a sense of struggle, almost biblical. Curator: That fits well, because photography like this provides a tangible link to the lives of ordinary people at the turn of the century. Think about the fisherman and his boat; we know the effort that this image asks of them. The wet sand and raw utility. It speaks of a daily struggle for subsistence in a specific locale. The photo itself would have involved the careful selection and preparation of materials; the glass plate, the chemicals, and the labour involved. Editor: I am struck by how that very “struggle for subsistence” becomes a powerful symbol of human endurance. Note the two figures, heads slightly bowed, mirroring each other, emphasizing humanity against the backdrop of an indomitable, ever-changing sea. And even the boat itself, the vessel, appears as a kind of primal symbol, connected to so many traditions and beliefs over millennia. Curator: Absolutely. By focusing on the material and practical reality, we understand those symbolisms better; what it means to actually man and maintain that boat; the types of fish they were hoping to catch to feed their family. Editor: True, but in viewing it, one cannot ignore that the act of fishing connects them to the earliest foundations of myth; survival. We respond viscerally to these themes—water, land, labour—these are universal and recurring motifs throughout the history of imagery. Curator: Looking closely at the surface reveals signs of wear; scratches and minor imperfections. This texture adds depth and confirms the image’s age, turning the print into a kind of artefact as well as artwork. The image shows us process, not as a perfect replica, but with real grit, a physical trace of making. Editor: Indeed. But this 'artefact' also transcends the tangible. The muted colours allow one to think deeper; perhaps those men on the shore have hopes and worries just like we do today. We project onto their silhouetted shapes—our own desires, hopes and concerns—creating a timeless tableau that transcends its historical specificity. Curator: So while you’re looking at a profound moment of time, a certain slice of humanity, it’s worth remembering too, it’s through the photograph that those slices are framed and that the labour it records is made manifest for our consideration today. Editor: Yes. I would only add that through recognizing universal symbolic visual anchors, it allows an aged image to find new light today, inviting continued interpretations, and confirming our shared humanity with subjects captured over a hundred years ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.