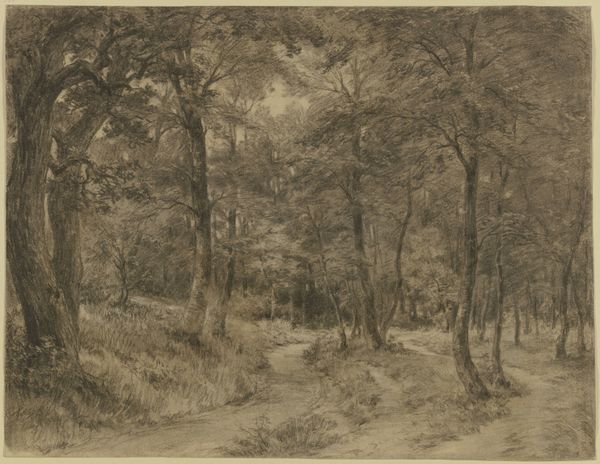

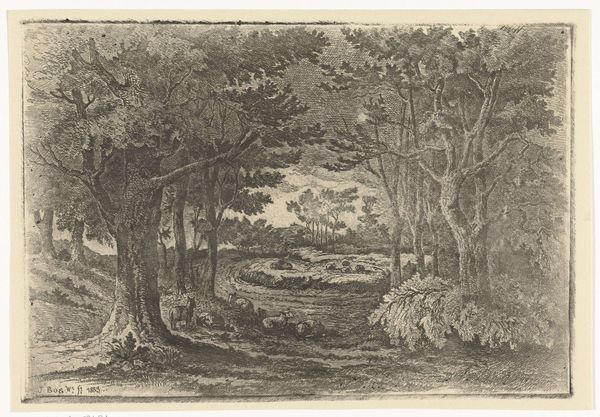

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

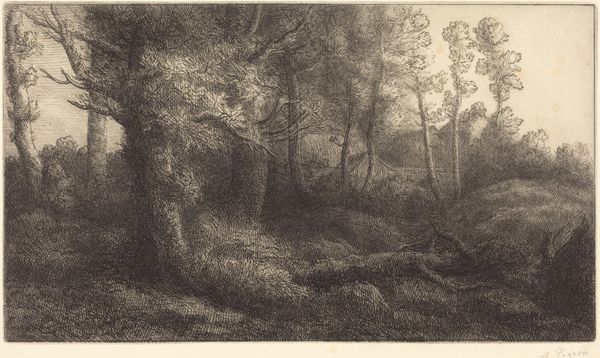

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

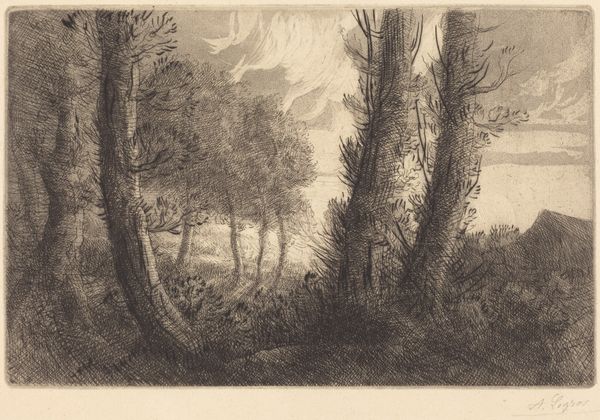

landscape

#

german

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

graphite

Copyright: Public Domain

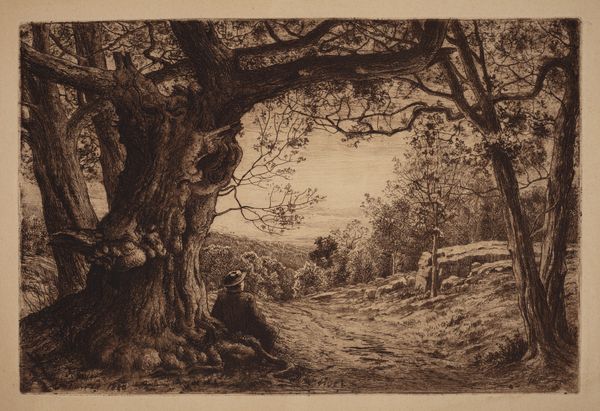

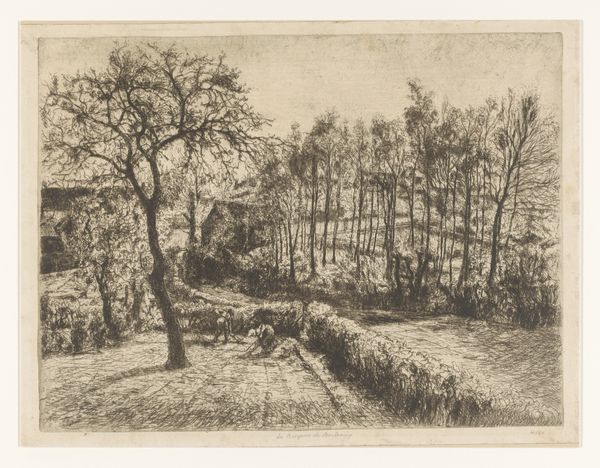

Editor: We’re looking at Eduard Wilhelm Pose's “Pinienwald mit einem Büffelkarren,” or “Pine Forest with a Buffalo Cart," rendered in pencil and graphite. It gives me a rather peaceful feeling; there’s this real sense of depth as the path recedes. What’s your take on this piece? Curator: I’m drawn to how it participates in the 19th-century art market’s embrace of Romanticism and nationalism. Notice how the figures driving the buffalo cart are so small, almost swallowed by the imposing nature around them. Editor: It really does put humans in perspective. Curator: Exactly. The landscape isn't just a backdrop; it becomes a reflection of the soul. The meticulously rendered forest could be interpreted as a projection of German national identity, echoing similar trends in other European artistic circles at the time. What kind of imagery would convey these messages to the viewers? Editor: Well, the seemingly untouched nature does imply a sort of inherent purity, and I suppose the farmers suggest an honest, hardworking population tied to the land. Curator: Precisely! These images of unspoiled nature helped cultivate and celebrate a sense of shared national heritage in the developing public sphere. And what role do you think museums play in upholding these kind of imagery? Editor: By putting works like this on display, museums essentially validate and reinforce those narratives. I never really considered the link between artistic taste and nation-building before. Curator: These landscape pieces offered idealized views deeply rooted in contemporary social and political sentiments. Looking at this, I’m struck by the power art has in constructing these historical perspectives. Editor: I agree, thinking about it, I’m definitely going to think of the social context more often now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.