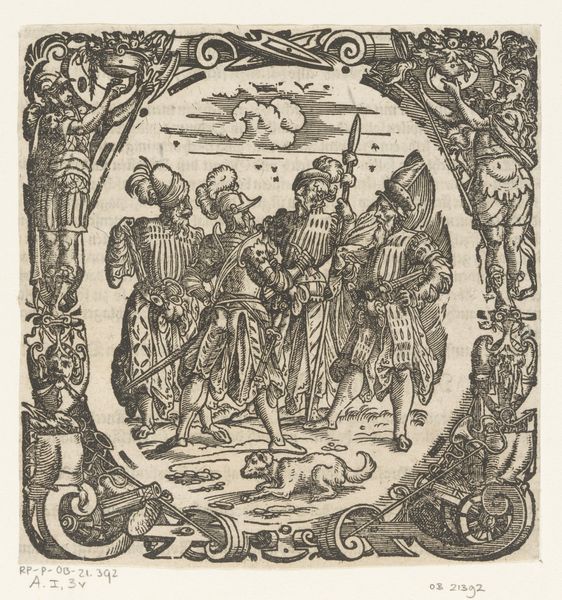

Scene with Misericordia and Veritas in a Circle at Center 1580 - 1600

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

female-nude

#

child

#

men

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

male-nude

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (14 × 13.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Scene with Misericordia and Veritas in a Circle at Center" by Theodor de Bry, made sometime between 1580 and 1600. It's an engraving, currently held at the Met. I’m struck by the intense detail – the swirling lines and how much is packed into this small circular format. What draws your attention in this piece? Curator: Well, looking at this engraving through a materialist lens, I immediately think about the process. Consider the labor involved in producing these intricate lines with engraving tools. The very act of making this print – and making multiple copies of it – speaks to a specific system of production and distribution in the late 16th century. Think about the access it provides, disseminating imagery more widely than paintings, but also standardizing the image. Editor: So, you're saying the *process* is just as important as the content, the figures of Mercy and Truth? Curator: Absolutely! What's striking is that it democratizes access but standardizes meaning, turning the depicted allegory into a commodity, in a sense. De Bry’s skilled use of engraving as a technology is crucial for understanding the work. How does that fine detail and reproductive quality shape our understanding of the female nude, for example, as both an object of beauty and a signifier of moral concepts? Does the print’s form influence how we interpret the depicted figures and the concepts they represent? Editor: I see what you mean. We're not just looking at the final image but thinking about the whole context of its creation and how it was consumed. Considering the intended audience, were these mass-produced engravings widely available, or mostly accessible to privileged social classes? Curator: That's an important question. Printmaking served varied functions; popular and devotional prints could be more widely disseminated, while finer prints such as this would appeal to a wealthier, educated market interested in allegorical subject matter and collecting such virtuoso displays of craft. So, the image and its consumption also reflect social stratifications of the period. Editor: That really reframes how I see the piece! I was so focused on the figures themselves and their symbolism, but considering the labor, materials, and social context gives it so much more depth. Curator: Exactly! And that's what looking at art through a materialist perspective can offer – a deeper understanding of not just *what* is depicted, but *how* and *why*.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.