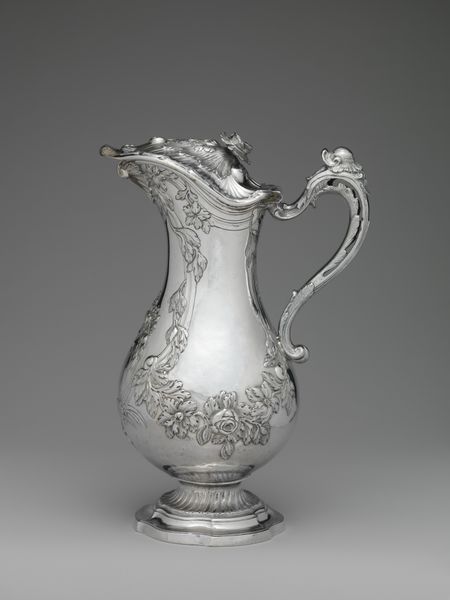

Dimensions: Height: 12 15/16 in. (32.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this stunning silver ewer. Crafted around 1784-1785, this piece, attributed to Jean-Baptiste-François Chéret, is a remarkable example of late Rococo craftsmanship currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Wow, it shimmers. The figure emerging from the top—it gives me such a conflicted feeling of classical grace meeting almost unbearable servitude, forever leaning to pour but never quite doing so. It’s lovely but feels heavy. Curator: The material reality certainly communicates wealth and status. Beyond pure functionality, the intricate chasing and sculptural detail position this ewer as a testament to the skill of Parisian silversmiths during the late 18th century, showcasing their meticulous handcraftsmanship. The piece bridges function and artistry. Editor: Absolutely. Look at how the artist integrates that sculptural element – a draped, neoclassical woman - into the form as both ornamentation and a literal component. I find myself wondering about her implied narrative; eternally caught between pouring and simply being there. Who was she intended to be, do you suppose? Curator: One assumes it represents one of the mythological graces or handmaidens, given that Neoclassical themes were increasingly popular. Yet beyond her potential symbolic identity, consider also the social context—the demand for highly embellished pieces during this era reflected aristocratic patronage. It mirrors the rise of manufacturing sophistication, but contrasts starkly against brewing political unrest that fueled revolution just a few years later. Editor: It really brings up that duality doesn't it? The meticulous refinement against the impending storm of social upheaval. I wonder, holding something like this – beautiful but, as we mentioned, *heavy* – were the elites completely blind to their place in this unbalanced material exchange? Curator: It's a vital consideration! Production meant skilled labor – time spent polishing, engraving—demanding intensive hours for artisans to satisfy elite cravings. Its surface bears the cost of many hidden processes that directly challenge any simple appreciation for aesthetics; a very complex reflection. Editor: Precisely. In some ways it reminds us of how the beautiful surfaces of art are seldom complete pictures, but more accurately are embedded objects of intricate stories. Curator: Indeed, we come away seeing that its significance lives beyond surface gleam.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.