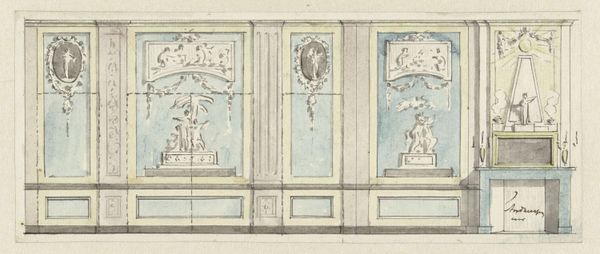

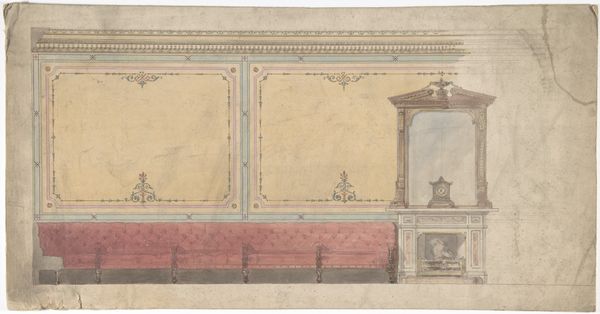

Elevation of a Wall with Two Windows and Five Wall Lights 1820 - 1900

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 5 1/8 x 10 11/16 in. (13 x 27.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This work, found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is called "Elevation of a Wall with Two Windows and Five Wall Lights," likely created sometime between 1820 and 1900. Editor: It's fascinating, but initially strikes me as quite restrained. The pale blues and grays create a sense of formality, almost austerity. It lacks the overt grandeur one might expect from a period interior design. Curator: Restraint, maybe, but look closer at how the unknown artist employed drawing and print techniques—likely pencil—to capture this vision. Think about the labor and precision that goes into recreating the illusion of marble and intricate details within architectural drawings and prints, and consider how such reproductions democratized access to elite design. Editor: That's interesting, seeing how reproducible design impacts access. What social contexts allowed such architectural visions? I immediately start considering who inhabited this space, and whether those chandeliers reflected the labor exploitation happening at the time. It calls into question issues of wealth and privilege. Curator: And we can explore those contrasts even in the drawing itself. The rigidity of the wall's construction, carefully replicated on paper, plays against the softer patterns mimicking marble or the flowing lines of the light fixtures. Were those chandeliers custom made, sourced through trade, or merely stylistic options to be chosen for the space? The artist offers us glimpses into both production and potential consumption. Editor: Right! The chandeliers themselves. Objects reflecting status while the means of illuminating elite spaces demanded dangerous, often marginalized labor. The drawing becomes less about mere design and more about those obscured power dynamics. And this particular elevation—does it exist? Was it a blueprint for actual creation, or a rendering presented to clients? Curator: Excellent point. That relationship between idea and built environment underscores the essence of the work. A print of architectural intent raises essential questions about who gets to define tastes and live within embellished surroundings. It highlights design not merely as aesthetics, but as applied skill. Editor: The rendering serves almost like a theater set, an environment performing upper class existence. Looking beyond simple aesthetic admiration into examining historical and socio-political landscapes enriches not only our knowledge of that moment but sharpens contemporary issues regarding equitable design. Curator: So, the careful observation and technical execution evident in this rendering gives us tools not only for historical study, but also for a critical look at art’s involvement in broader discussions. Editor: Indeed. This seemingly formal interior opens up dialogues far beyond interior decorating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.