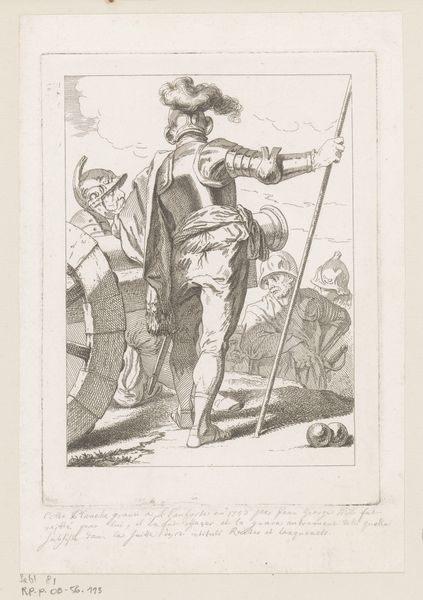

Standing Officer Holding a Lance 1755 - 1771

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

soldier

#

men

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Image: 4 3/16 × 2 13/16 in. (10.6 × 7.2 cm) Plate: 4 3/4 × 3 5/16 in. (12 × 8.4 cm) Sheet: 5 3/8 × 3 3/4 in. (13.7 × 9.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Standing Officer Holding a Lance" created sometime between 1755 and 1771 by Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, a compelling engraving. Editor: My first thought is the line work; it’s incredibly detailed but feels almost… playful? There's a vibrancy despite the historical subject. And is he barefoot? Curator: Indeed. It's fascinating how Loutherbourg depicts this officer—certainly an attempt to connect him with the past, invoking perhaps a Roman commander or some other historical military figure, although with those bare feet… Editor: I am also curious about the status and purpose of engravings such as this at this moment in time. Was this aimed at an elite audience of collectors, or was it produced to educate the public, shaping how the military and warfare was percieved? I suppose these would shape public sentiment. Curator: Very astute. Engravings like this had a dual purpose. On one hand, yes, they circulated among collectors interested in historical and military subjects, fueling a fascination with the past. But they also served as visual propaganda, subtly shaping public perceptions of power and military might. It’s interesting that printmaking served to spread Enlightenment ideas about history, even as its subject often depicted aristocratic military leadership. Editor: The detail on the armor versus the looseness of the background, almost as if rendered by different hands, makes me think about labor divisions in the print shop, about how the final object's consistency relies on distinct types of workmanship. Did the studio specialize? How are we to understand printmaking within a capitalist frame? Curator: That is fascinating to think about in regards to the division of labor and its influence on aesthetics! In terms of specialisation: absolutely, large printmaking workshops often had specialists focusing on different elements like figures, landscapes, or ornamental details, adding layers to our appreciation of it as a manufactured item and its historic agency. The Met acquired the work in 1888 which probably added a certain type of distinction at this time. Editor: A fitting purchase date, given the growing appetite of museums for items of this kind during that period. Looking at it now, I think what stands out to me is this print’s reminder of the complex relationship between artistic skill, historical narrative, and the means by which art enters into public consciousness. Curator: For me, thinking about the socio-political and the popular function that such a piece would fulfill in its era makes this unassuming little image particularly powerful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.