lithograph, print

#

neoclacissism

#

lithograph

# print

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 572 mm, width 395 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

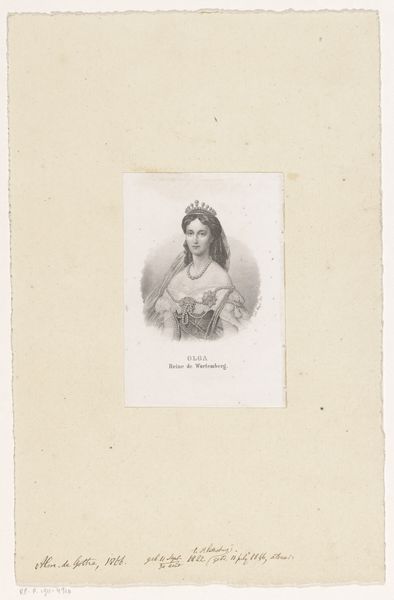

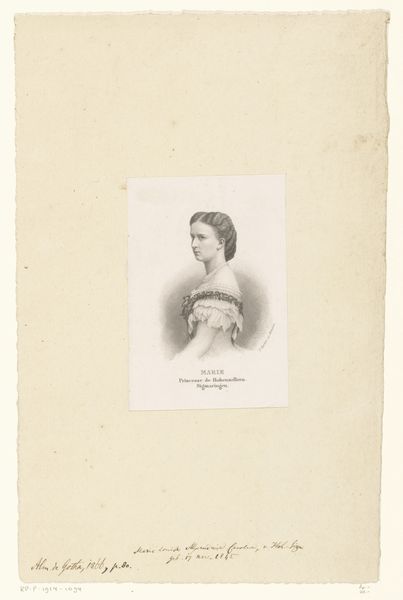

Editor: So this is "Portrait of Eugénie de Montijo," a lithograph from 1853 by Marie-Alexandre Alophe, housed in the Rijksmuseum. It’s quite stately, almost… fragile, isn’t it? All that lace and the pale coloring gives a delicate feeling. What’s your take on it? Curator: That sense of delicacy you perceive is key. Think about the context: Eugénie de Montijo was not born into royalty. Her marriage to Napoleon III was intensely scrutinized and controversial. This portrait, therefore, becomes a careful construction of imperial femininity, designed to legitimize her position. How does that understanding shift your perspective? Editor: It definitely makes me think about the performativity of power. It's not just a likeness; it’s a statement. But how does the artistic style reinforce that? Curator: The Neoclassical elements – that column in the background, the emphasis on idealized beauty – evoke a lineage of power, connecting her to historical empires. And the Realist style, striving for accuracy, suggests authenticity. The lithograph, as a readily reproducible medium, then circulates this carefully crafted image far and wide. Editor: So it’s not just about capturing her image, but about disseminating a very specific idea of who she is and her role. Curator: Precisely. The portrait operates as a form of political propaganda, working to secure her position and the stability of the empire, by referencing and rewriting existing narratives around gender and power. In what ways do you see her personal identity erased in this piece? Editor: I see it in the lack of any truly unique feature. It is hard to get a sense of the person. It’s more of an ideal, which, when framed as a statement of political intent, complicates my understanding of portraiture. Curator: Exactly, seeing beyond the aesthetic surface helps us uncover the complex societal forces at play. This portrait is not just an artwork, but a potent instrument of political and cultural meaning making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.