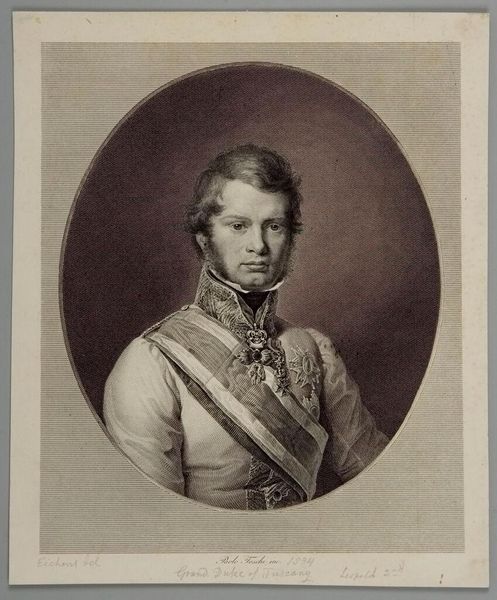

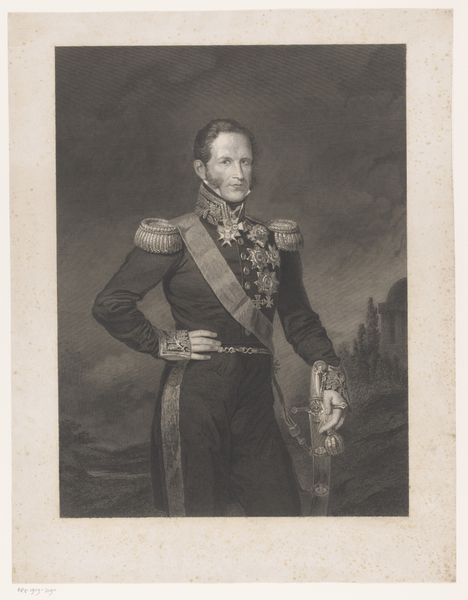

Portrait of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany 1831 - 1833

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

romanticism

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 16 7/8 × 12 5/16 in. (42.8 × 31.3 cm) Sheet: 21 3/8 × 15 1/16 in. (54.3 × 38.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Gazing at this piece, I am struck by a sense of quiet dignity, almost melancholy. The soft gray tones give it a certain gravity, a timelessness. Editor: Indeed. What we are looking at here is "Portrait of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany," rendered in the years 1831 to 1833 by Paolo Toschi. It exemplifies the conventions of the portrait style during the Romantic period. The medium is an engraving, lending to the clear detail in Leopold's facial features and attire. Curator: The symbols of power are quite interesting here. I'm immediately drawn to the sash and medals—visual markers denoting status, position. There’s a visual language at play about hereditary roles, I'd venture to say. But he's young; is there youthful naiveté? It contrasts against the symbols that burden his person. Editor: His position was interesting for sure. Toschi executed this likeness, situating Leopold's role as head of state amidst complex political transitions. Remember, Leopold, despite some reforms, was often caught between liberal desires and Austrian imperial interests, thus making his status delicate to execute visually. Curator: That really hits. There's this kind of softness that comes through Toschi’s engraving. A man shown in uniform that gives no clues, his story kept secret in time as it fades through an oval vignette—his symbols tell the story without words, echoing that internal push and pull you mentioned earlier. Editor: The detail of the rendering enhances this further; Toschi uses shading meticulously to cast shadows around the Duke’s face, which contributes to this atmosphere. What's intriguing to me is also how museums play into the narrative: locating these portraits today reinforces ideas of continuity but perhaps also entrenches certain power structures within our cultural institutions. Curator: Absolutely. I find myself wondering about Leopold's own thoughts, then, as well. An engraving made in multiples allows for visual ubiquity that can become embedded in the public's perception of a leader, making the image its own power symbol. It serves as a conduit for discussing our interpretations of leadership even now. Editor: Indeed. Reflecting on Toschi’s creation provides insight not only into the image but into ourselves— how we interpret authority and history through carefully crafted symbols. Curator: Agreed, the symbols of a bygone era continue speaking today if we choose to listen closely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.