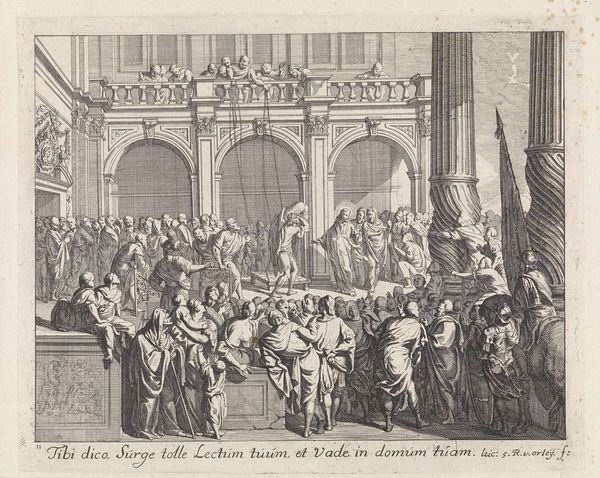

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 273 mm, width 303 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, "Bruiloft te Kana," or "The Wedding at Cana," attributed to Nicolas Cochin, though based on an earlier work, dates from sometime between 1620 and 1681. The sheer scale of the composition is impressive for a print, with all those figures. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: Beyond the scale, I’m drawn to the political implications embedded in representing a biblical scene within such an opulent setting. Notice the architectural grandeur, the classical columns. This isn't just about depicting a miracle; it's about aligning religious narrative with power, wealth, and a specific cultural ideology. Who do you think this representation served? Editor: It feels like it’s trying to legitimize something. The Church maybe? The patrons? Curator: Exactly. Baroque art often functioned as propaganda, reinforcing the authority of the Church and the aristocracy. Consider, too, how the composition stages this event. The elite are elevated, literally placed at a higher level, overlooking the scene. It subtly reinforces social hierarchies and notions of divine right. Does this influence your view of the wedding being depicted? Editor: Definitely. It shifts the focus from the miracle itself to the power dynamics surrounding it. It’s less about the water turning into wine and more about who's in charge and who benefits. I hadn't thought about it that way at all at first. Curator: And that's the power of contextualizing art. By exploring the social and political landscape in which it was created, we can unveil its deeper meanings and challenge the dominant narratives it presents. Editor: Absolutely. Looking at it now, I'm seeing much more of a commentary on social structure than a straightforward retelling of the biblical story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.