Copyright: Public domain

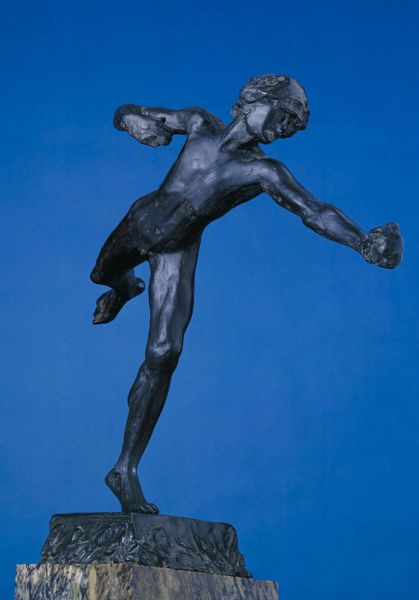

Editor: This is "Walking Man," a bronze sculpture created around 1900 by Auguste Rodin. The figure's incompleteness and exaggerated movement make it feel strangely powerful and vulnerable at the same time. What are your thoughts when you look at it? Curator: It's a figure stripped down to pure motion, isn't it? Rodin wasn't after a literal representation. He captures the *idea* of walking. Think about that tension in the pose – the legs striding, but the absence of arms and a head, a kind of elegant amputation. What does that absence do to how you experience his power? Editor: It's like he's missing vital pieces but still carries on with such vigor. I guess, makes you wonder where is he going or why? It suggests a deeper struggle, like pushing through life's challenges. Curator: Exactly. There's a sense of raw energy, almost primal. Rodin originally conceived it as part of a larger work, "The Gates of Hell", so we know there is no context beyond the movement, and Rodin then takes it to even bigger scale to become an individual and unique work. He had quite the internal wrestling match, constantly breaking down and rebuilding the human form. Can you almost feel that conflict in the rough texture of the bronze? Editor: Yes, now that you mention it, you can definitely see the fingerprints and marks of the sculpting process. Curator: Which makes the sculpture almost…alive. For me, it speaks volumes about the human condition – striving, enduring, always in motion, despite our inherent flaws and limitations. What do you take away from it now? Editor: It's less about a destination, and more about the journey itself, about persistence, which is actually very encouraging. Curator: Perhaps it’s the imperfections and the gaps that truly make the art so powerful, a reminder to see beauty and meaning even in what is fragmented.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.