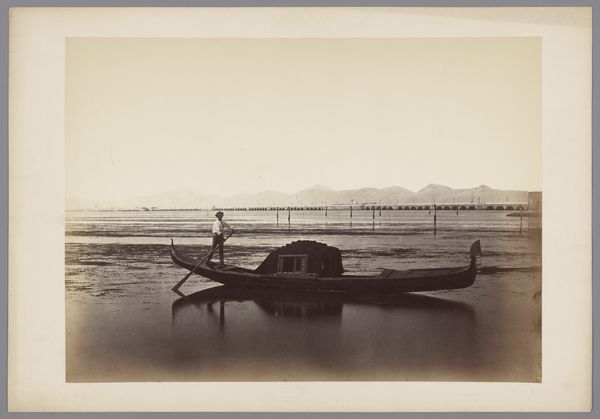

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: 5 3/8 x 6 11/16 in. (13.65 x 16.99 cm) (image)17 x 12 5/16 in. (43.18 x 31.27 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

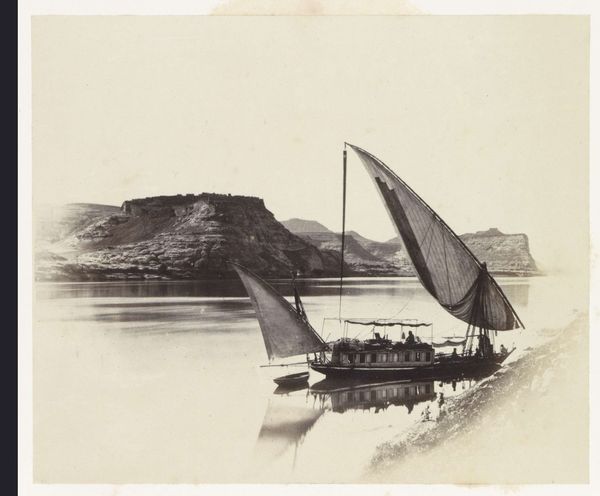

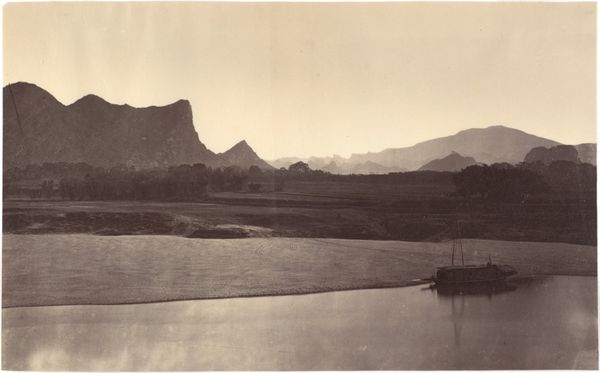

Curator: Looking at this gelatin silver print, “Travellers Boat at Ibrim” by Francis Frith, created around 1860 and held here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I'm immediately struck by how serene the whole scene feels. It has this quiet, reflective quality to it. Editor: Yes, serene… until I zoom in on the boat and remember what this image truly represents. What I first saw as peace turns a bit melancholy. Curator: Ah, you’re keyed into the symbolism. I think Frith’s work often gets caught between the romance of Orientalism and the realities of 19th-century imperialism. His large-scale photographic projects across the Middle East were both artistic endeavors and commercial ones, feeding a European appetite for images of the ‘exotic’ East. Editor: Exactly! Ibrim itself, that imposing citadel in the background, held such significance over centuries as a center for various cultures and powers in Nubia. Its depiction here feels more like a scenic backdrop, stripping it of its layered histories and local meaning. It transforms into a passive object within the colonial gaze. Curator: That’s a valid point. His compositional choices, like the boat taking up a good portion of the foreground, do suggest a focus on the traveler’s experience—that of the European tourist—rather than the landscape itself. Editor: Even the light, almost hazy and dreamlike, lends to this feeling of distance, of a world observed from afar rather than engaged with directly. But in truth the very style itself - the crisp details afforded by the photographic technology of the time paradoxically add another layer to that sense of remoteness. The tonal range of the print evokes the passage of time in the landscape depicted but its light emphasizes a specific moment for an outsider, rather than something that persists through local interaction. Curator: So it's the photographic object that is meant to speak in time, as an artifice. Though that speaks also to the broader Victorian context too—an era fascinated by travel and exploration but equally steeped in unequal power dynamics. How do you see its lasting legacy? Editor: Images like these became foundational in shaping Western perceptions, almost becoming a sort of visual shorthand for imagining the Middle East. While aesthetically captivating, they must be examined alongside their complex role in reinforcing existing cultural narratives of dominance. Curator: It's fascinating to unpack the many layers embedded within this single photograph. Editor: Indeed. It is always necessary to ask what something represents beyond what it simply portrays.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.