Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

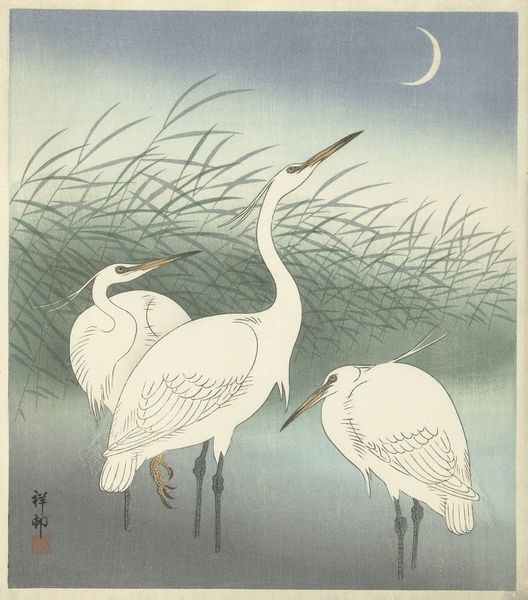

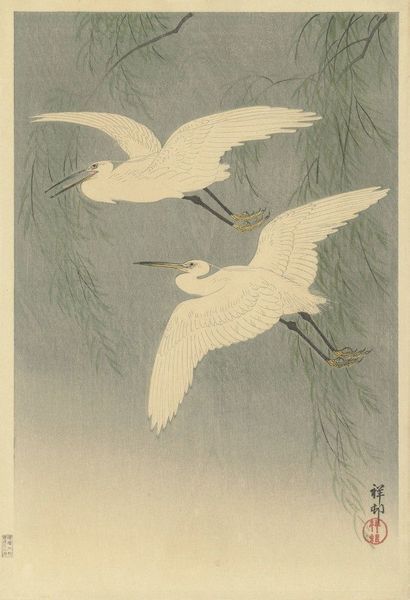

Curator: Standing before us is “Little Egret,” a woodblock print by Ohara Koson, likely created between 1900 and 1930. Editor: It has a serene, almost melancholic feel. The limited palette emphasizes the bird’s luminous whiteness against the soft, muted grays of the water and reeds. There’s an overwhelming sense of quiet observation. Curator: Absolutely. The single egret is a potent image. In Japanese art, birds often represent different emotional states or seasons, with the egret specifically associated with purity and perhaps even solitude, given its stark white plumage and the marsh environment it inhabits. It appears self-contained. Editor: Thinking historically, the rise of ukiyo-e prints, and woodblock prints more broadly, was deeply entwined with commercial culture and distribution to an expanding middle class. Is there anything we know about who would have acquired this image and how they may have viewed it at the time? Was it part of a set, perhaps? Curator: Indeed. Koson became highly regarded during a period when Japanese prints were gaining popularity in the West, shaping how Japan was perceived abroad. There was a considerable market for such images as exports. As such, birds-and-flower prints, or kachō-e, have a very important symbolism. In Japanese iconography, such a composition serves as a vehicle to convey ideas about harmony and the cyclical nature of life. It shows an ephemeral beauty rooted in something solid and continuous, Nature. Editor: The strong linear design, typical of ukiyo-e, enhances this. Notice how Koson uses simple lines to evoke movement in the water. There's tension, or better call it an interaction, between tradition and modernity—a negotiation which can explain, in turn, the success this type of images experienced in a moment of great socio-political transformations in the Meiji Era and beyond. The bird is beautifully captured and seemingly still, yet alert. It projects the expectation of movement about to happen. Curator: Exactly. It's a masterful depiction that balances realistic detail with elegant simplification. It speaks to deeper notions of impermanence but at the same time, offers the image of life constantly recreating itself from within. Editor: And as a historian, I see the print’s impact extending beyond the art world, playing a part in shaping cultural exchanges. Thank you, the nuances you revealed deepened my appreciation. Curator: It has been my pleasure. The egret, suspended between stillness and motion, water and air, embodies so many concepts, cultural memories, and potential meanings, and, ultimately, this open nature of symbols make of it a powerful representation, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.