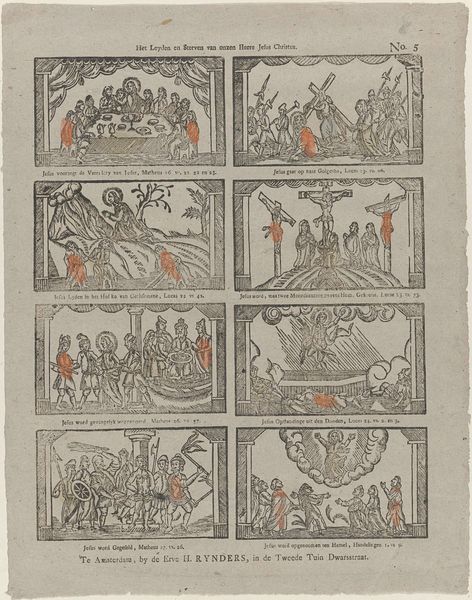

Het lyden van onzen heere en heyland Jesu Christi 1761 - 1804

0:00

0:00

ervendeweduwejacobusvanegmont

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 417 mm, width 329 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

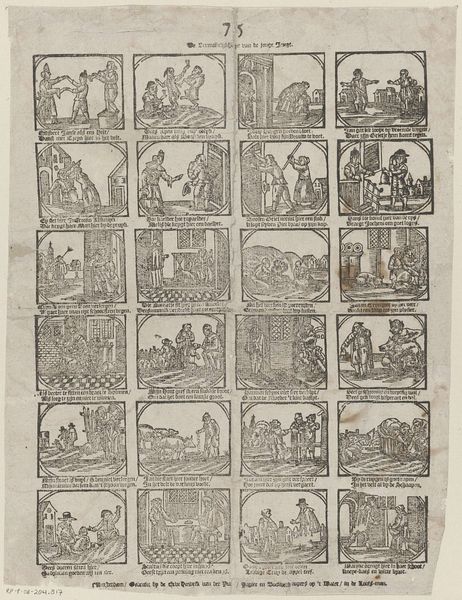

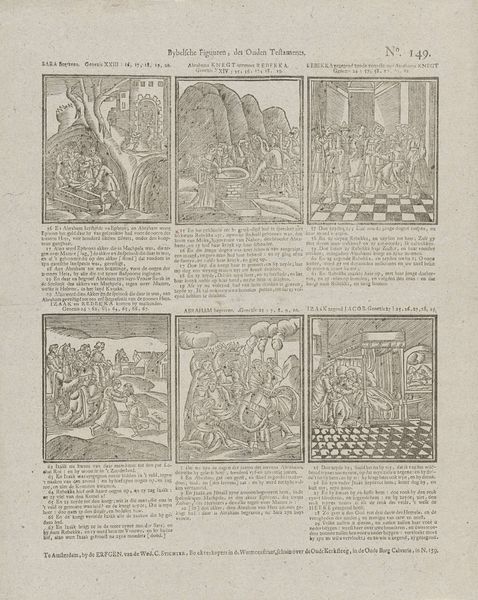

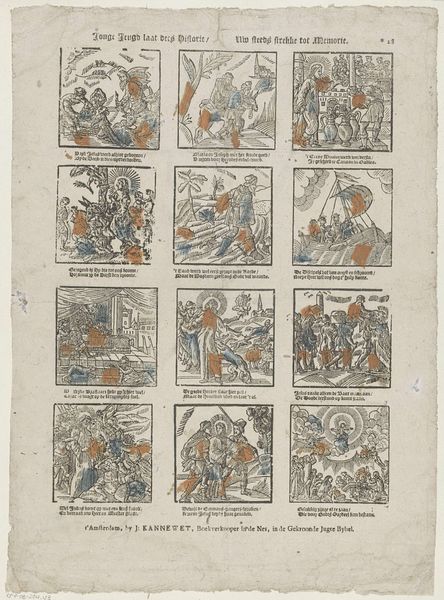

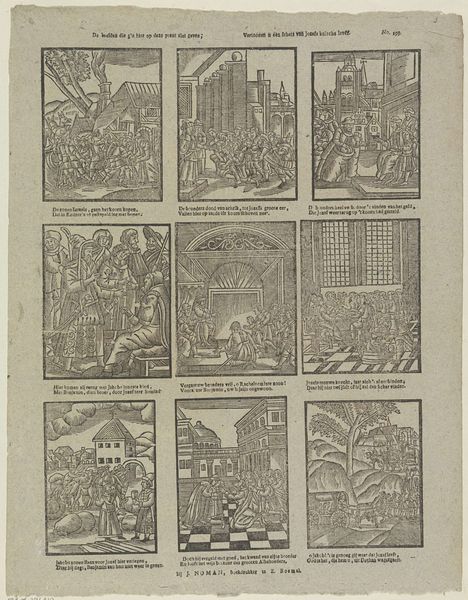

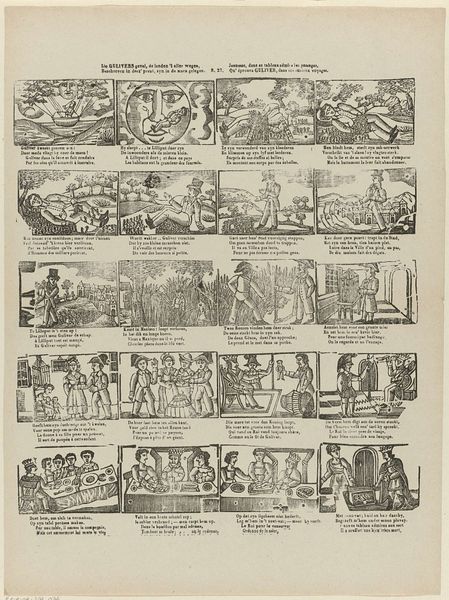

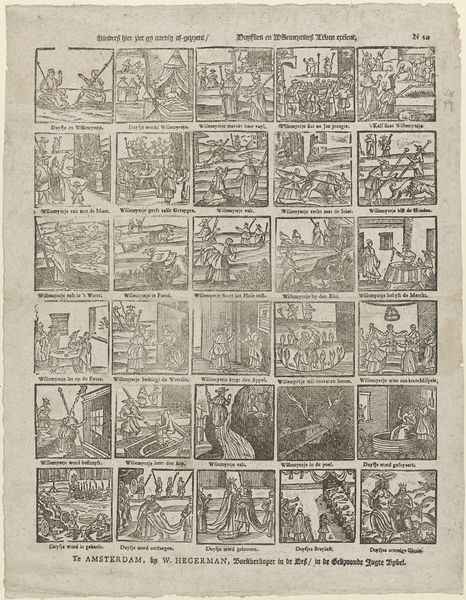

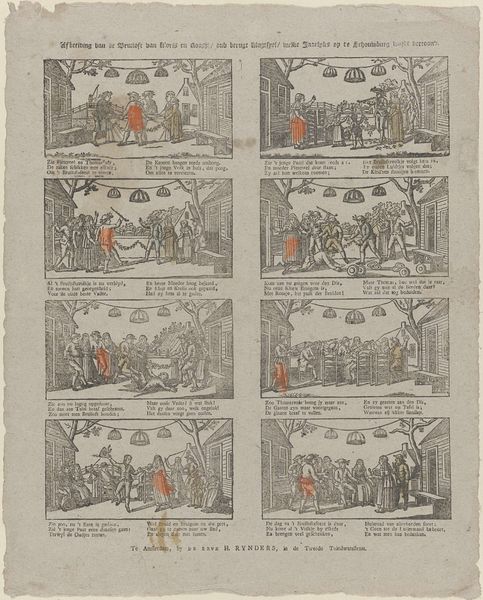

Editor: We’re looking at "Het lyden van onzen heere en heyland Jesu Christi," a print from between 1761 and 1804, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It’s made with engraving and the design looks like scenes from the Bible arranged in square panels. I find its old style charming. What do you see in this piece that maybe I am missing? Curator: What strikes me immediately is how this print embodies a specific cultural moment, a visual encoding of religious narratives deeply entwined with power structures of the time. Think about the accessibility of religious texts then; prints like this brought biblical stories to a wider audience. Who held the power to disseminate these stories and how did it serve their interests? Editor: So you are suggesting that these images, even religious ones, could be viewed as forms of social control? Curator: Absolutely. The selected scenes, the artistic style – even the act of mass production – were all carefully curated. Baroque style served emotional engagement to reinforce specific doctrines. Consider who created and distributed the print. What were their economic or political interests in shaping these narratives? Who was excluded or marginalized? Editor: That's a fascinating point; I hadn't thought about how much the producers' motivations shape religious art. It almost reframes it. Curator: Exactly. Looking through a lens of power and representation transforms the way we perceive seemingly straightforward religious imagery. Editor: I see now that art reflects culture but can also enforce it. Curator: Precisely! Always question the status quo. This approach to art is not just about aesthetics or religious expression; it's about understanding the intricate relationships between art, power, and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.