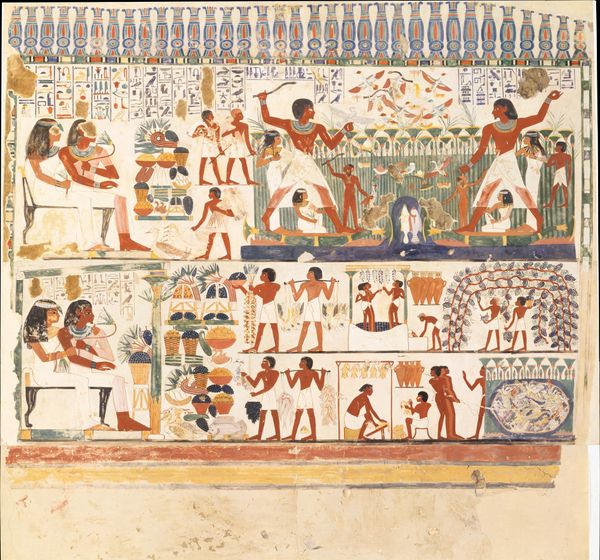

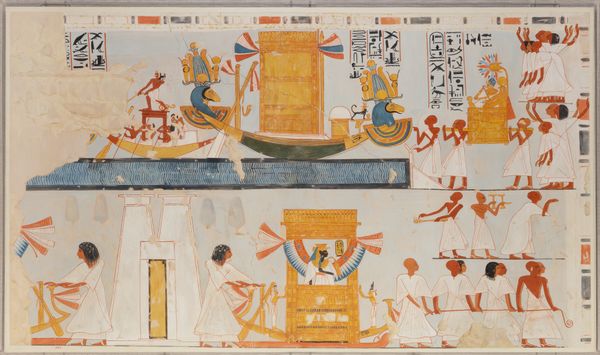

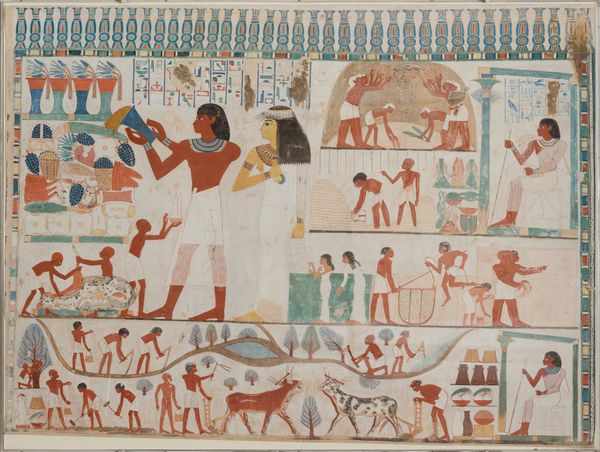

Sennedjem and Iineferti in the Fields of Iaru 1295 BC

0:00

0:00

painting, watercolor

#

water colours

#

narrative-art

#

animal

#

painting

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

egypt

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

men

#

miniature

#

watercolor

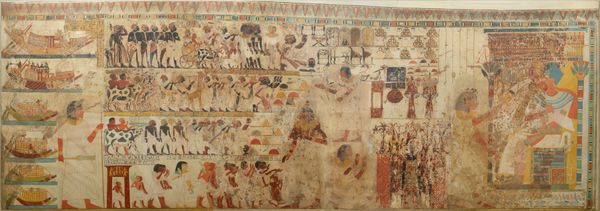

Dimensions: Facsimile H. 54 cm (21 1/4 in); W. 84.5 cm (33 1/4 in); Framed H. 58.1 cm (22 7/8 in); W. 88.6 cm (34 7/8 in) scale 1:2

Copyright: Public Domain

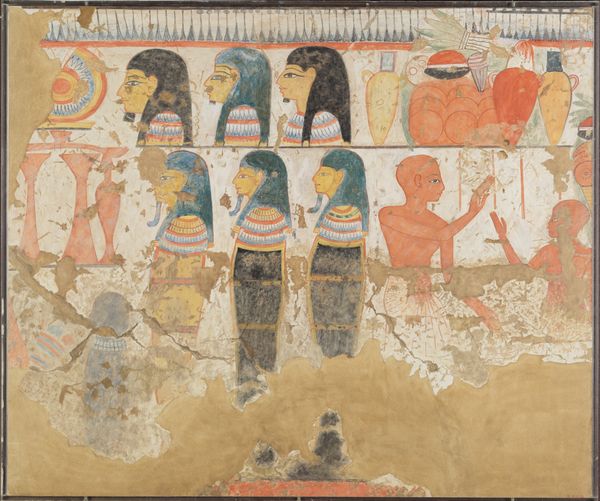

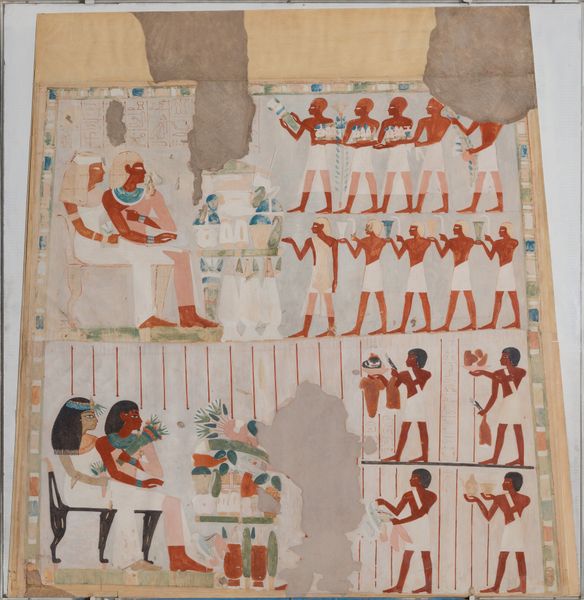

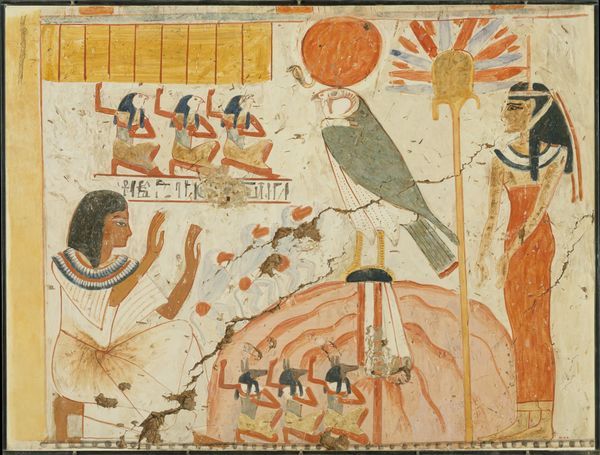

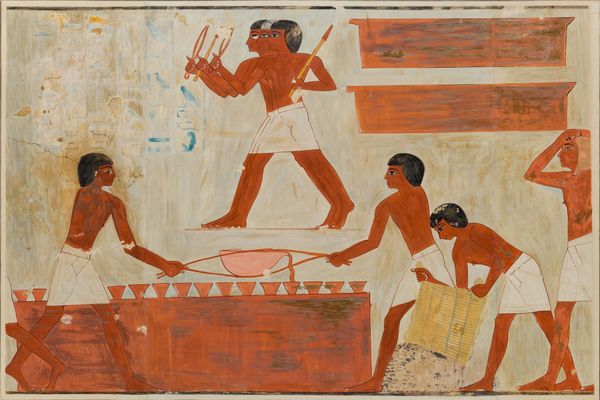

Curator: Looking at this artwork, my immediate impression is of tranquility and abundance. It feels like stepping into an idyllic world. Editor: Well, you've landed on a key element, certainly! This watercolor on papyrus depicts Sennedjem and Iineferti in the Fields of Iaru, dating back to around 1295 BC, now held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Fields of Iaru, according to ancient Egyptian beliefs, were a paradise reserved for the afterlife, a mirror image of earthly existence, but perfected. Curator: So, it’s an imagined landscape of afterlife rewards. Looking closely, it does appear like an idealized agricultural scene, with Sennedjem and Iineferti participating in the harvest. I notice a repetitive visual motif—labor is the theme; the continuous loop of production even follows the family into the afterlife. Editor: Precisely! These scenes aren't just idyllic depictions. They illustrate the means of production in ancient Egypt—how resources were cultivated and processed. What tools were employed, the roles assigned within the family, the literal and symbolic yield and its implications to an Egyptian cultural identity in life and death. Curator: This also touches on gender roles. Women are often portrayed assisting with tasks like winnowing or tending to the fields. What is interesting, though, is how these figures are flattened, almost stylized—it gives an impression of timelessness. It’s not just about them, but about every family’s struggle and effort. Editor: Absolutely. Labor, in this context, isn't solely a physical activity; it's intrinsically linked to sustenance, familial duty, and social position. Notice, for example, how animals are integrated into production and consumption in these fields. Curator: Yes, I see the spotted cow, so well fed, carefully placed. It all creates an idea of utopian prosperity and social order through manual labour. I can imagine how this painting acted as an empowering and culturally stabilizing tool. Editor: Indeed. By analyzing art through the lens of production and labor, we get deeper to a perspective on society. It lets us rethink Egyptian high art by centering ordinary people’s day to day struggles and envisioning death. Curator: I found the idea of how deeply intertwined death, gender, family, and work are through Egyptian society extremely interesting. This idealized depiction has surely provided many generations with reassurance. Editor: I’m glad we both agreed to that! Through labor, materials, gender and the human and non-human relationship to them we got an insight into that specific culture and civilization.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.