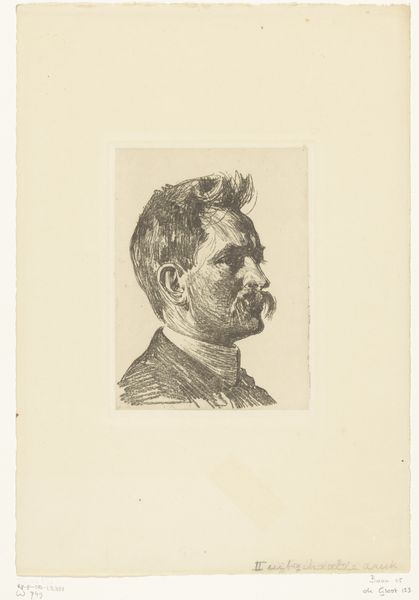

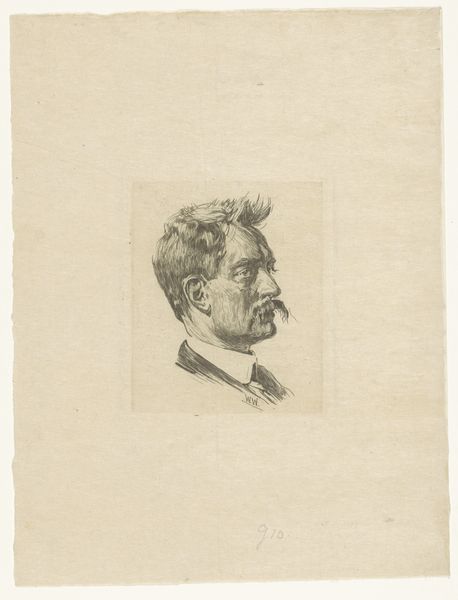

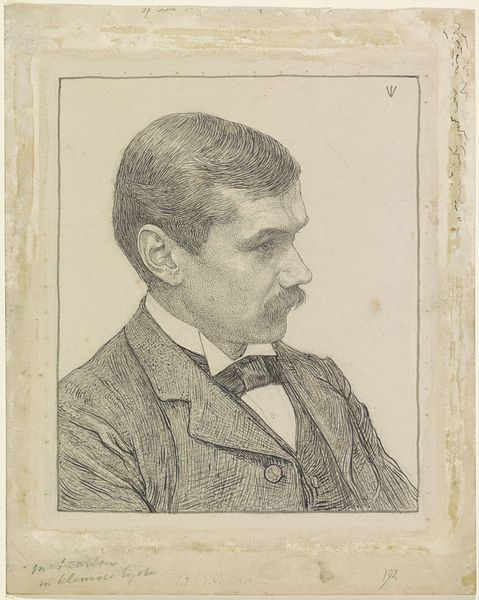

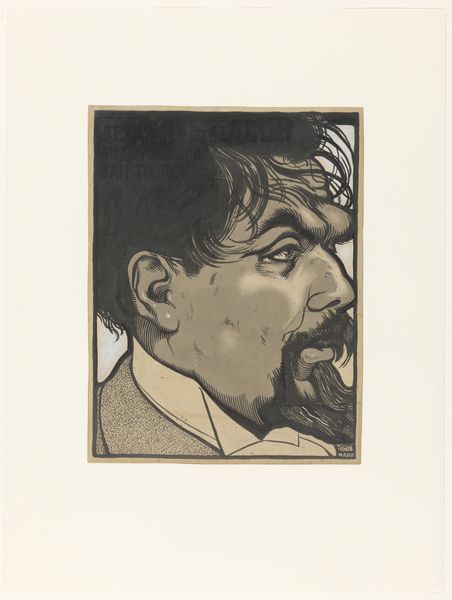

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

portrait

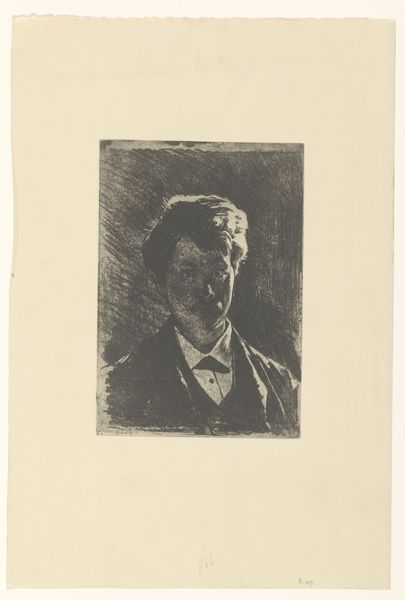

#

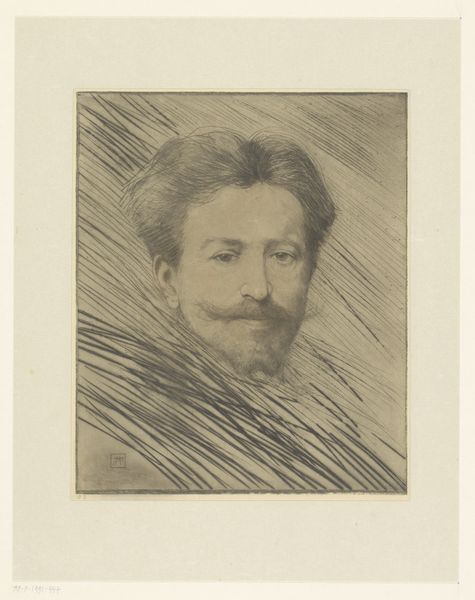

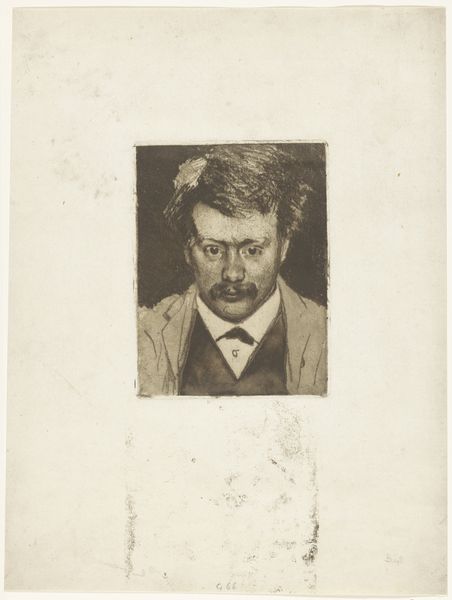

graphic-art

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

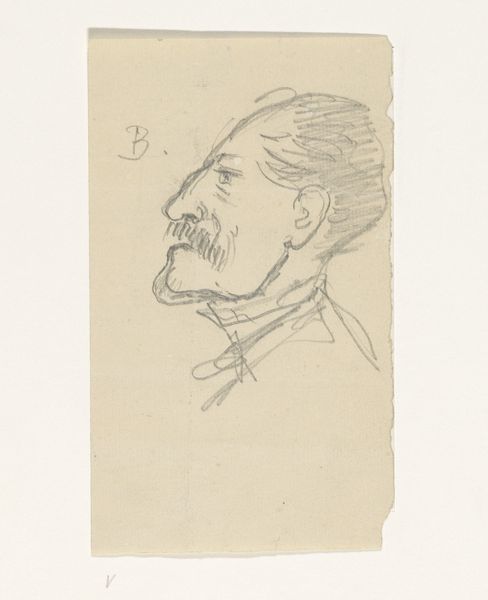

caricature

#

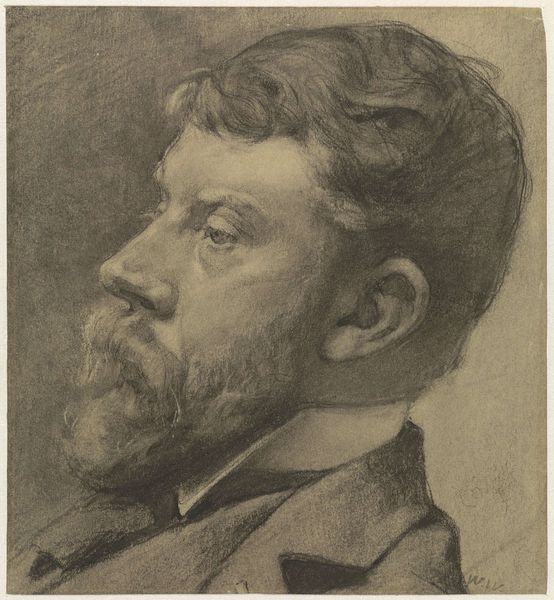

charcoal drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 132 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

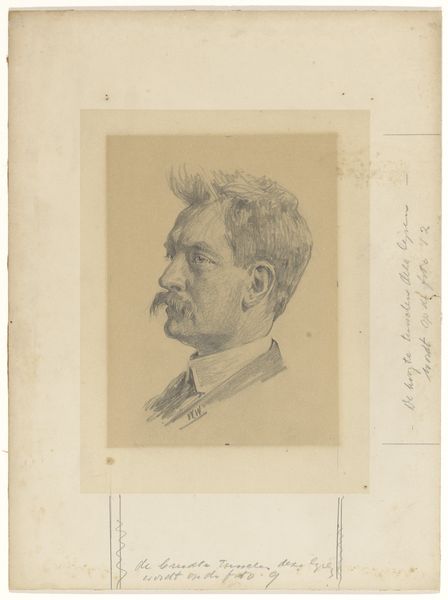

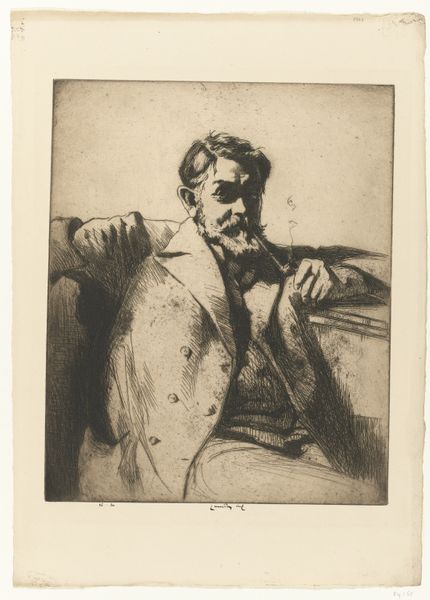

Curator: What a dapper fellow. Bernhard Pankok’s “Portret van Emil Orlik,” created in 1897, certainly catches the eye, doesn’t it? Editor: It’s like a little theatre happening on paper! That ochre skin tone against that sickly-sweet olive background is quite a striking first impression. Is this… graphic art, printmaking? It's very much of its time, Art Nouveau, but also sort of darkly humorous, like a stage caricature. Curator: Spot on! It's an engraving, part of the explosion of graphic arts at the fin de siècle. You see how Pankok is working in such sharp lines? Almost making the very medium itself a feature! But that’s typical for the era; look at how he rendered Orlik’s booming hair and the very angular mustache. Every detail pushes into the decorative—it's as if Orlik himself is a constructed thing, an artwork already. Editor: Yes, all those decisions around tools and reproduction speak volumes! Was this a commissioned portrait or more of a reflection of Pankok's peer group? And how does making art *about* making art reinforce social stratification – who gets portrayed and by which materials? Curator: Well, it helps knowing that Emil Orlik himself was a graphic artist of some repute! I imagine the print here is a subtle homage. I think there's this beautiful tension in that—Orlik, as both subject and fellow artist, is at once observed and knowing, both exposed and in on the joke! Editor: And Pankok seems to relish the control he can exert with engraving - emphasizing features, flattening perspective... It's almost violent, the act of translating a person through the press, rendering them in such graphic detail! Curator: Precisely! Think about how the Art Nouveau aesthetic emphasized artifice, how it sought to blur the line between fine and applied art. Perhaps, then, what seems harsh to you in his method is just part of the whole cultural impulse. In any case, it remains a compelling, lasting work that makes me ponder just that idea: at which point do we as people become constructions, as characters—or simply art ourselves? Editor: Absolutely. Understanding this print deepens the story—from artistic friendships to artistic economies and processes. Now *that* changes everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.