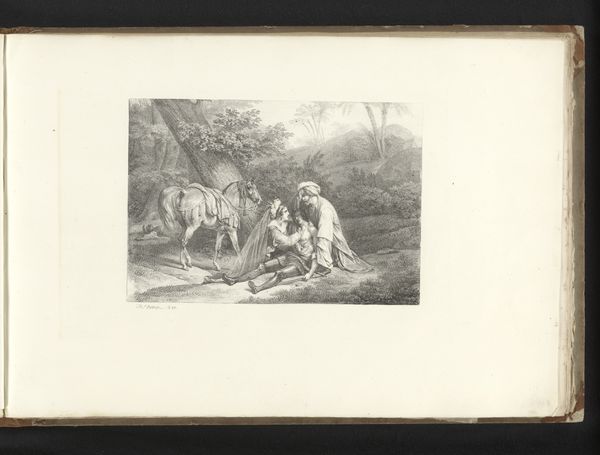

drawing, lithograph, print, paper, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 370 × 528 mm (image); 477 × 669 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

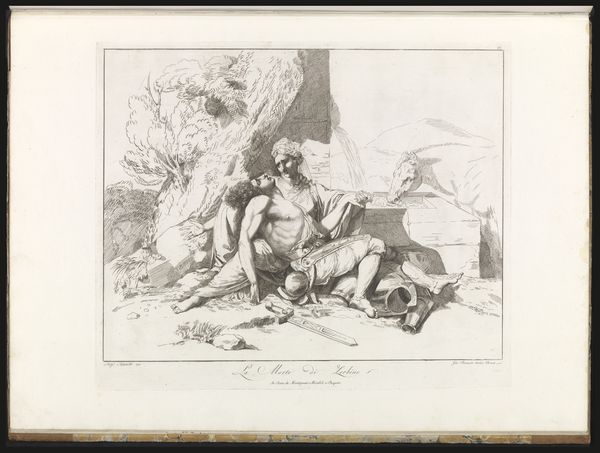

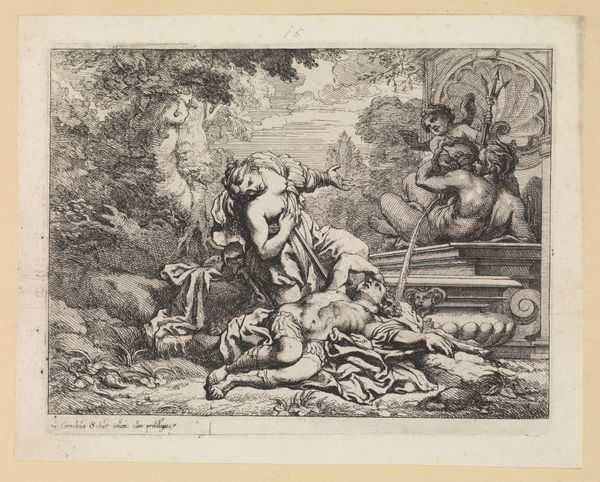

Curator: This is Joseph Anton Rhomberg’s "The Mourning of the Dead Abel," a lithograph from 1818, now residing here at The Art Institute of Chicago. It certainly makes an immediate impression, doesn't it? Editor: It does. The composition is arresting—the stark foreground contrasts with the distant landscape, all rendered in such somber charcoal tones. It evokes a palpable sense of grief, though the figures' positioning feels slightly staged, like a tableau vivant. Curator: Staged grief perhaps reflecting its manufacture. Rhomberg’s choice of lithography—relatively new at the time—allowed for broader circulation of emotionally charged scenes. Printmaking democratized art. It meant this image of the ultimate familial trauma could enter many homes as commodity. What message was that manufactured reproducibility sending? Editor: A crucial detail lies in the figures' gestures. Adam’s pose, his hands clasped in what appears to be prayer. How can one read these physical attitudes? They seem to reference established conventions for representing lamentation, echoing classical sculpture. It adds another layer to the semiotic field this lithograph generates. Curator: Precisely. Rhomberg’s studio was likely equipped with plaster casts used for teaching and this scene, although biblical, also adheres to early 19th century theatrical and operatic gesture, an almost standardized repertoire. Consider that his more famous brother was a celebrated composer and think about where those stages and studios met in society, both shaping—and selling—emotions. Editor: The artist's choice to depict the figures in a stylized manner rather than aiming for strict realism adds to the feeling that the focus isn't merely the depicted event, but the universal emotion of loss. Abel's idealized physique contributes to the symbolism. Curator: The paper support itself speaks to the social context as well, right? The labor needed to make paper versus that of carving into wood for block prints; the wider distribution of these lighter sheets all connect back to the evolving art markets of the early 19th century. Each element shapes the reading, both of the image itself, but also in its contemporary usage. Editor: It’s fascinating how an artwork can encapsulate so much within a relatively small frame. Curator: Yes, a tangible manifestation of artistic choice that we can both trace in terms of materiality and the ideas embedded within its composition.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.