print, paper, ink, engraving

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

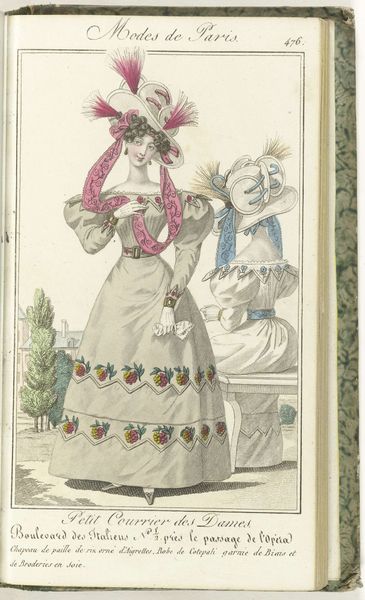

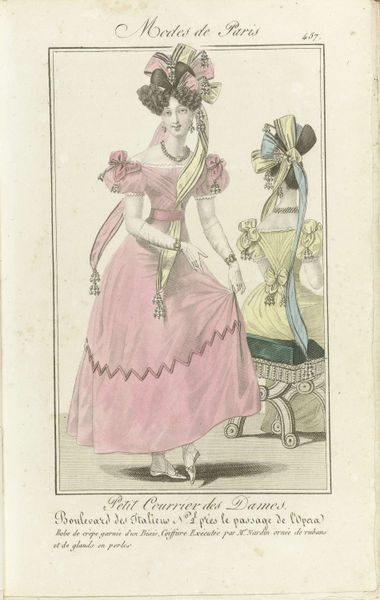

Curator: This delightful print is titled "Petit Courrier des Dames, 1829 nr. 647". The artist, regrettably, is anonymous. It is an engraving using ink on paper from 1829 currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: Oh, she looks incredibly constrained, almost doll-like! The frills and the puffed sleeves give an impression of being caged in… what a vision of accepted femininity at the time. Curator: Indeed. It reflects the Romantic era’s emphasis on emotion and perhaps, societal expectation. Look at the batiste wool, the straw bonnet adorned with Casmarina…these are materials signifying luxury. The production of textiles such as this were essential to Parisian and global trade, the raw materials extracted from colonized lands and refined by industrial processes—the work of many rendered invisible. Editor: And note the location mentioned in the print: "Boulevard des Italiens, near the Passage de l'Opera.” Fashion wasn't just about clothing; it was a performance in a public space dominated by class. Access to such a scene in 1829 came with distinct social barriers based on who you were and who you weren't allowed to be. Curator: Precisely. The production of such a magazine relies on distribution networks, artisanal skills and of course the demand and economic power of consumers. The 'Petit Courrier' implies small news or minor correspondence, but it dictated very seriously the visual culture of the time. Consider too how prints facilitated the reproduction of ideals beyond the elite who could afford them—influencing a broad section of society and defining gender roles. Editor: Right. Think about who this publication might have been for. Was it really "petit," in that, were all members of the public given an equal opportunity to express themselves and participate in fashion? Obviously not. These details subtly expose power dynamics and invite one to question what freedom of expression really looked like for most. Curator: Absolutely. So when we consider Romanticism, let's also consider the labour, the global networks and hierarchies of value underpinning it. What materials, whose work, at what cost, makes up the world of beauty we often take for granted? Editor: Right, so behind the decorative vision there are countless unheard stories…making it less romantic, perhaps, than initially presumed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.