drawing, lithograph, paper, pen

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

line

#

pen

#

genre-painting

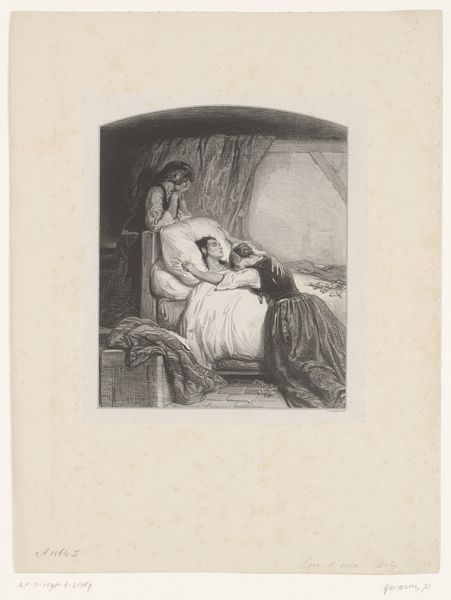

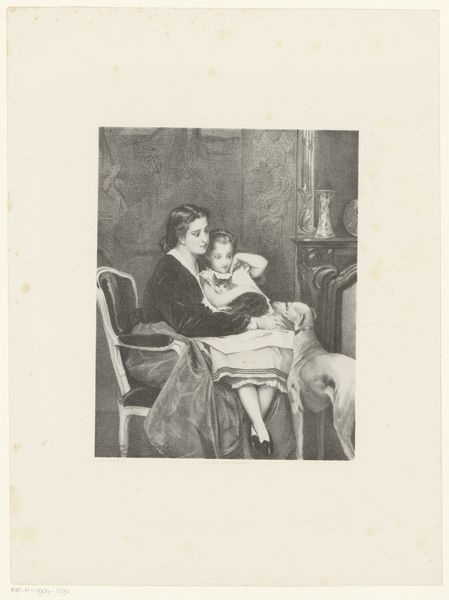

Dimensions: height 307 mm, width 234 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

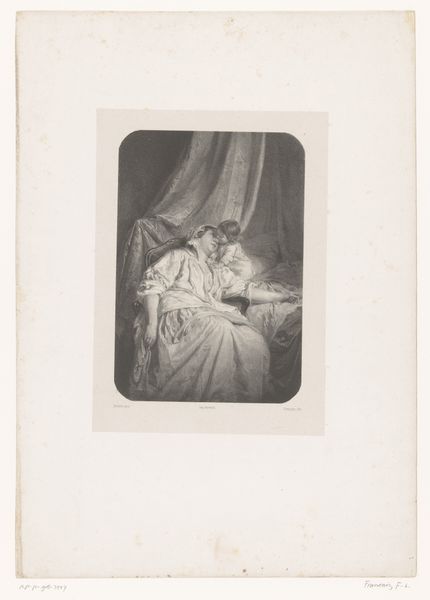

Curator: Looking at this lithograph, "Moeder leest boek met kind op bed", created around 1829 by Paul Gavarni, now held in the Rijksmuseum collection, the scene feels immediately intimate, doesn’t it? Editor: It does, but with an almost theatrical artificiality. The dramatic lighting, the heavy drapery… it’s like a stage set for domesticity, less a candid moment and more a posed tableau. Curator: Gavarni was a keen observer of social life in 19th-century Paris, and it is critical to consider the lithograph in the context of increased literacy and changing ideas about motherhood. Motherhood was really shifting as a virtue with social expectation during this era, a period of social changes due to industrialization, in France. Editor: You're right, it’s impossible to ignore that performative aspect. Look at the idealized features of both figures, especially the mother. It adheres to societal expectations placed on women—nurturing, refined. Does this image reflect reality, or does it contribute to a romanticized ideal, setting unrealistic standards perhaps? Curator: That tension is really at the heart of this work, isn’t it? Lithography allowed for the mass production of images like this, and in the distribution the role and place of women and their responsibility in educating the youth, this contributed to the construction, negotiation, and dissemination of social values. This work shows domestic spaces that reinforced the role of mothers and the private nature of the female sphere in a patriarchal world. Editor: Yes, it speaks volumes about the politics of imagery. Who is it made for, and who is the target audience? Considering the print's accessibility due to its medium, this kind of imagery arguably would further normalize traditional gendered domestic roles. Did Gavarni, consciously or unconsciously, help perpetuate this? Curator: That's a critical point. By situating it within the history of reproductive technologies, from lithography onward, we understand that this single image is actually part of a much larger and more powerful narrative, isn’t it? Editor: Precisely. These sentimental images were circulating widely at the time, playing an influential role, that would ultimately define much about cultural life at this time and still reverberates today. Curator: So, while seemingly simple and intimate, Gavarni's lithograph unveils intricate questions of gender roles, accessibility to resources for the family unit and power dynamics within the rapidly changing landscape of 19th-century society. Editor: A glimpse into the private world becomes, through art, a very public discussion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.