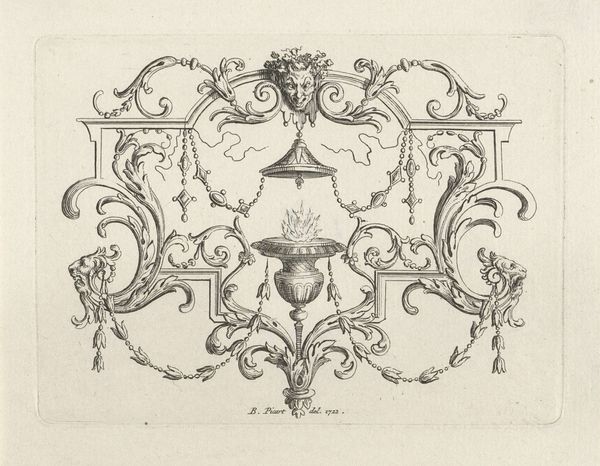

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 127 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a wonderfully intricate print! This is Bernard Picart's "François de Maucroix flanked by the Church and Hymen," created in 1718. You can see it here at the Rijksmuseum. It's an engraving, exhibiting incredible detail. Editor: It does strike me as a rather odd tableau. The subject, Maucroix, is elevated and flanked by...the Church and Hymen, god of marriage? The entire scene is contained within this ornate frame that almost overshadows the figures themselves. It feels very controlled, very much of its time. Curator: Absolutely. Baroque art often aimed to showcase power and virtue, using allegory as a key tool. Here, Picart is portraying François de Maucroix, a canon and man of letters, in an idealized manner. The Church, symbolized by the figure to his left, suggests his piety and devotion, while Hymen represents, perhaps, the fruitful outcome of his moral life, even without literal descendants. Editor: I am curious about the chains. Hymen holds chains loosely connecting to Maucroix, yet they don't seem to bind him. Is it more of a symbolic link, maybe referencing duty or societal expectation? The artist gives Hymen and Maucroix similar coloration, which does tie the pair together. Curator: Precisely. The chains likely symbolize the societal bonds that link individuals to institutions and to marriage, broadly considered. Hymen offers a connection to civic life, not so much literal bonds as a means for accessing continuity and respect within a moral framework. I read Hymen's offering more as a connection than as constraints. And the inclusion of the cherubic relief further underscores the connection to legacy and virtue, a promise made tangible through art. Editor: So the piece is projecting a vision of legacy achieved through institutional approval, framing its subject for posterity. The Church’s miter is interesting. Her hand is upon the subject’s outstretched hand as she extends a processional cross in the other, symbolizing both secular and ecclesiastic life being interwoven, almost one and the same. Is Picart perhaps suggesting an intertwined sense of institutional and personal validation? Curator: Yes, absolutely. That mingling is vital to its reading. We can read it as a cultural snapshot reflecting a hierarchical society where honor and reputation are inextricably tied to both spiritual and societal acknowledgement. Editor: It’s intriguing to see how Picart uses symbolism to weave this intricate narrative around Maucroix, reflecting the socio-political landscape of his time. Curator: Indeed. It serves as a reminder of the potency of images in shaping historical perception and legacy, which lingers with the viewer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.