print, paper

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paper non-digital material

#

pale palette

# print

#

sketch book

#

personal journal design

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

journal

#

letter paper

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 116 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

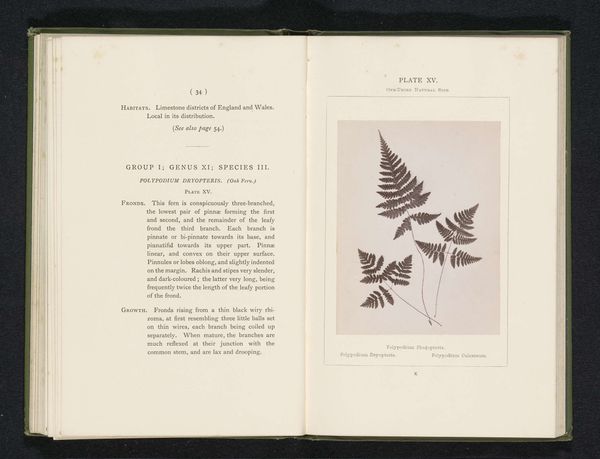

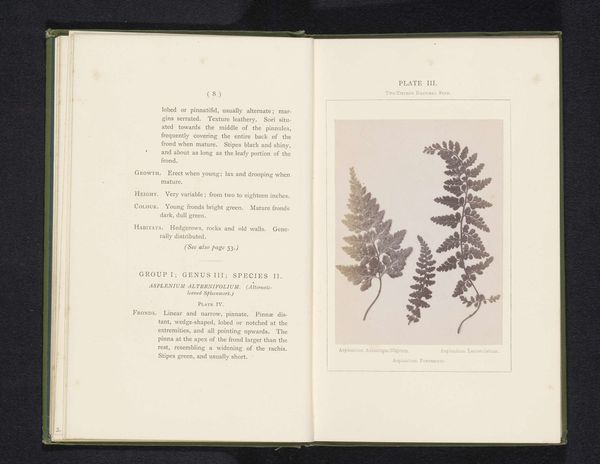

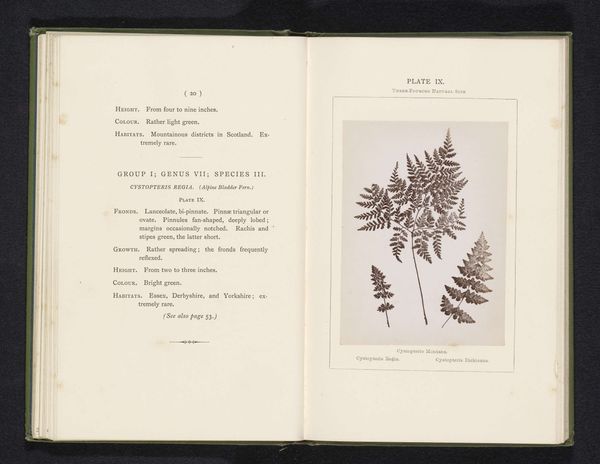

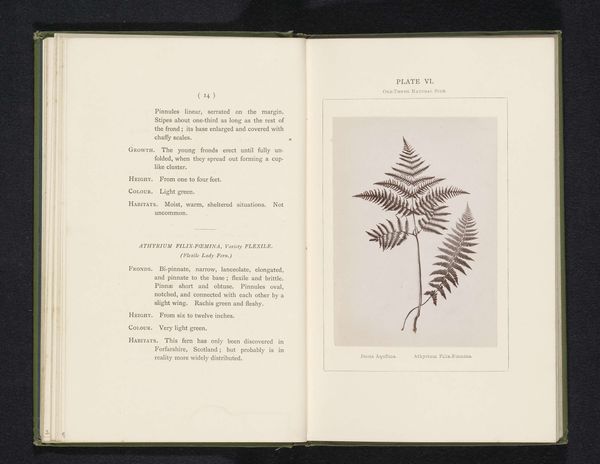

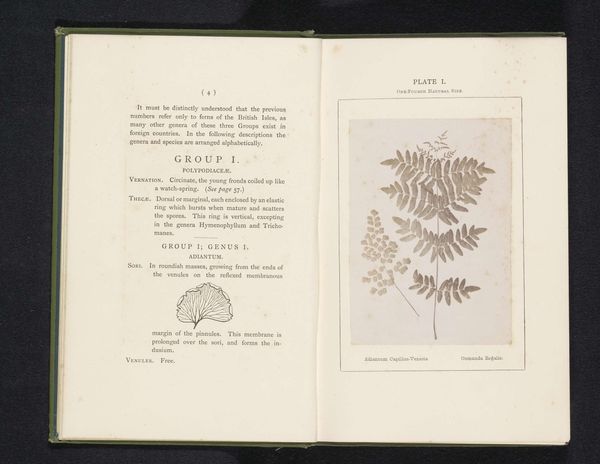

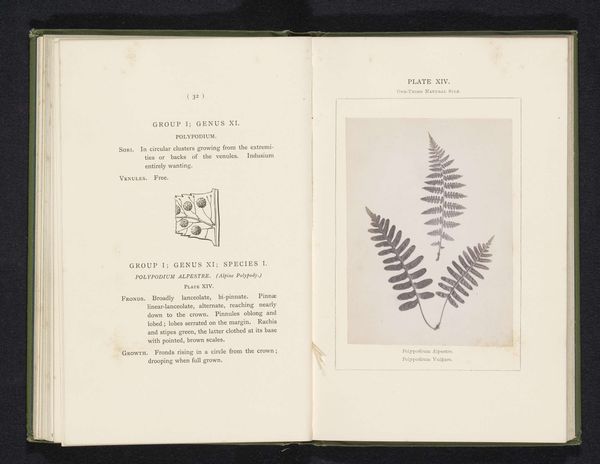

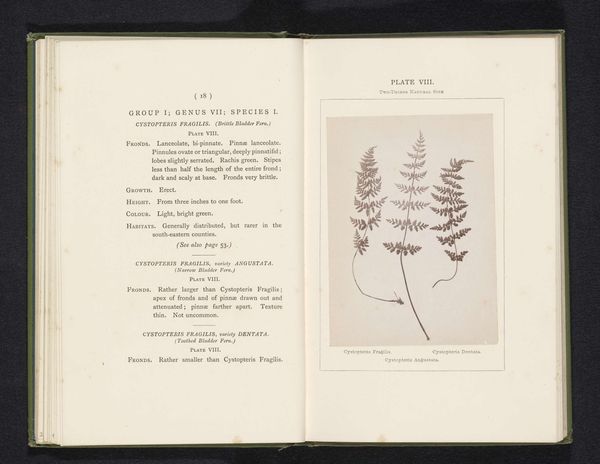

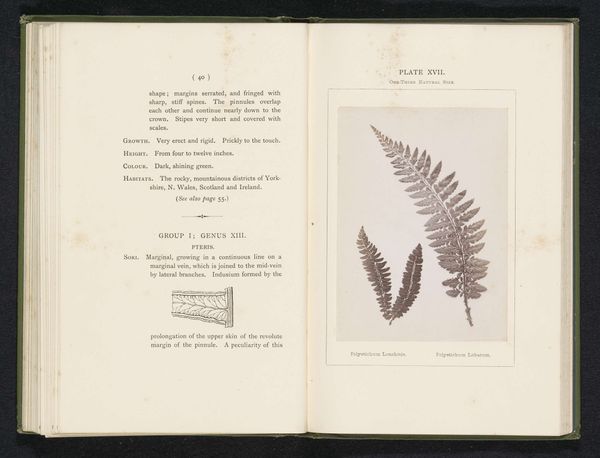

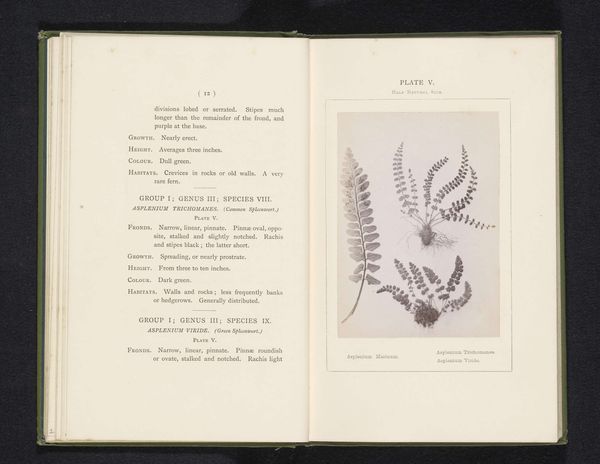

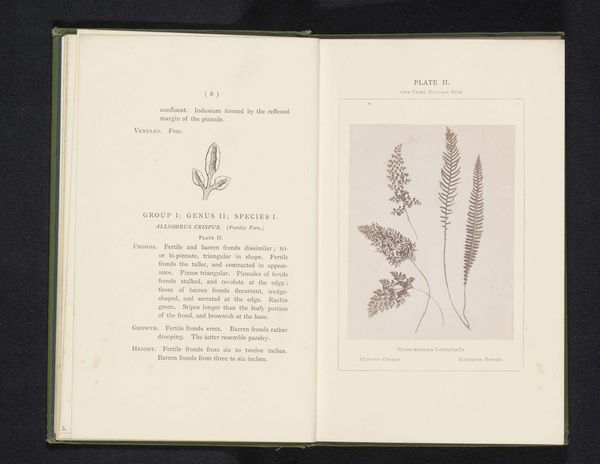

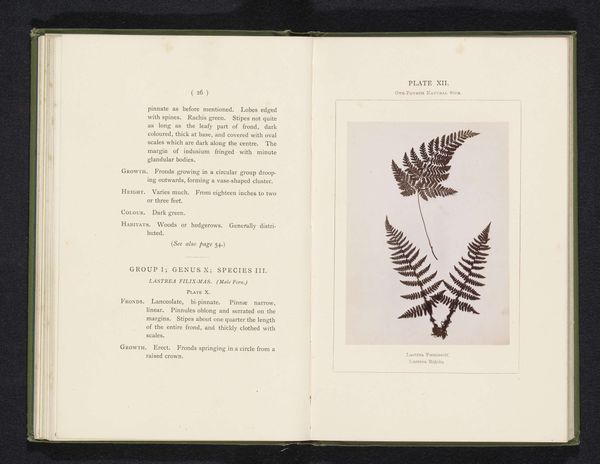

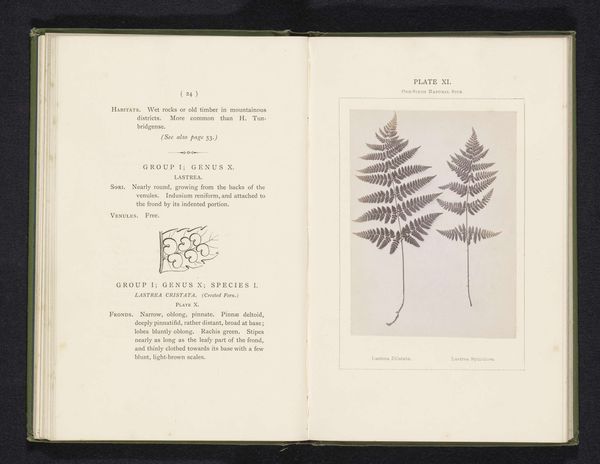

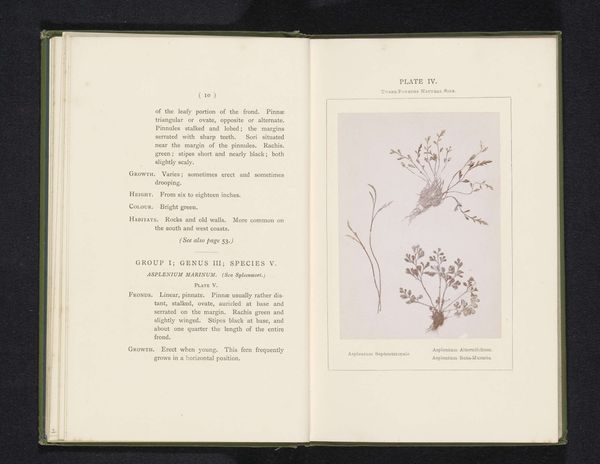

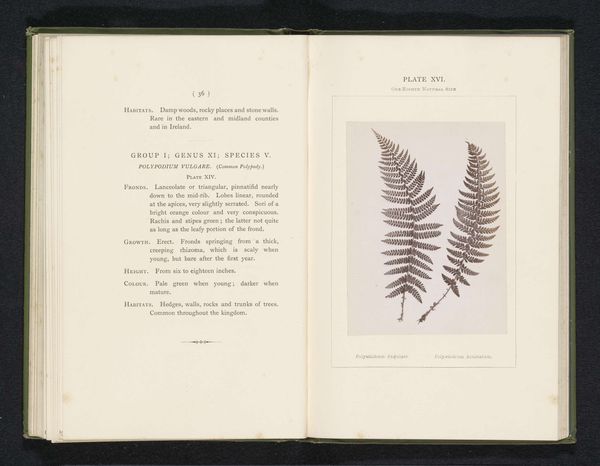

Curator: Look at this intriguing double-page spread. We're seeing "Bladeren van de schubvaren en twee soorten Hymenophyllum"— "Leaves of the scaly fern and two types of Hymenophyllum"— dating from before 1877, credited to Sydney Courtauld. It’s presented almost as if we’re viewing an open notebook or botanical study. Editor: My first thought is how incredibly delicate this appears. The paper seems so fragile, the impressions so light. It’s whispering to me of time and quiet observation. Curator: Absolutely. This feels very personal. Examining it closely, we notice the distinct texture and aging of the paper stock. Note also the old font of the text accompanying the detailed print work of each individual fern specimen. The whole presentation hints at meticulous labor involved in creating this study, raising interesting questions about its production and potential use. Was this intended for publication, or more for private scientific study? Editor: I wonder about the social context of botany at this time. Who was Courtauld? Was botany seen as an acceptable pursuit for women, or was she pushing boundaries with such detailed scientific renderings? And how were such images used? As references for industrial designs? Curator: Those are all vital points. The print work itself speaks to the printing technologies available and the skills needed to reproduce these natural forms with such precision. Someone had to craft these images, transfer them onto a printing surface, and meticulously reproduce them. This represents material engagement beyond artistic skill; a blending of craft, scientific endeavor, and print technology, with labor very much present in the final artefact. Editor: This notebook-like presentation also brings into question the politics of display. Presenting such study openly gives us a different connection to botanical art than viewing individual framed specimens on a gallery wall, as it invokes academic and perhaps scientific contexts more directly. The presentation shapes the way we view the art object, transforming an aesthetic observation into an exercise in naturalism. Curator: Considering these two elements, labor and contextual frameworks, makes it really clear this artwork exists because of specific material practices and is shaped by forces beyond the merely aesthetic. Editor: I agree. It really encourages us to think beyond just pretty depictions of plants and examine a confluence of forces including social conventions, scientific pursuit and the printing trade.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.