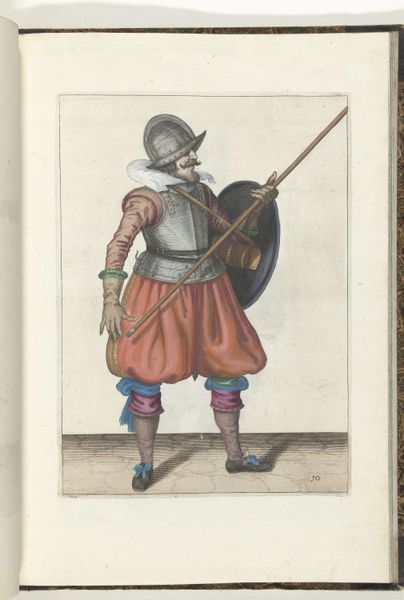

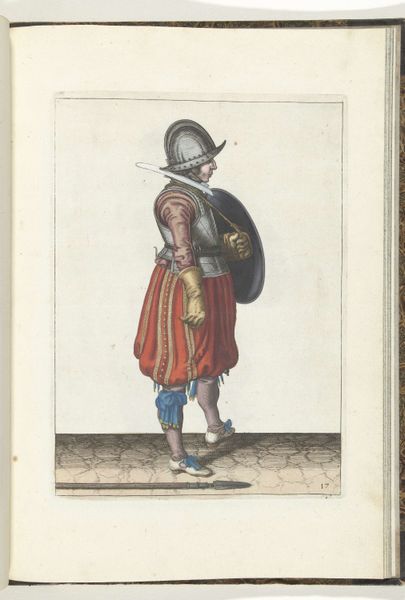

De exercitie met schild en spies: de soldaat presenteert zijn rapier met de hand niet hoger dan zijn gezicht (nr. 19), 1618 1616 - 1618

0:00

0:00

drawing, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

coloured pencil

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

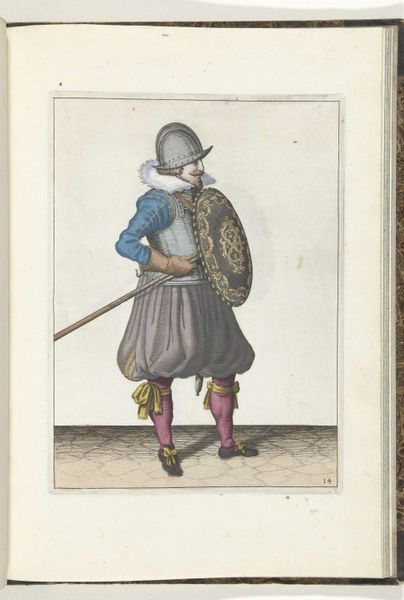

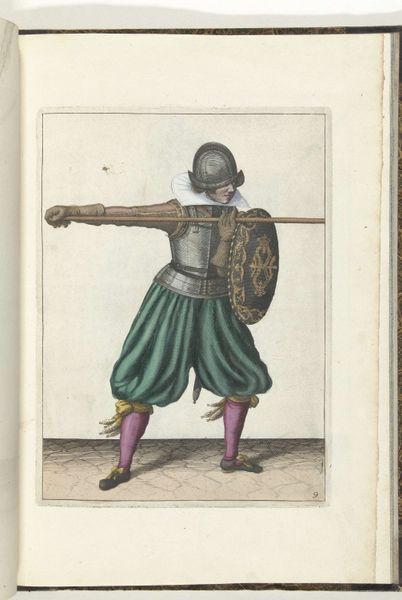

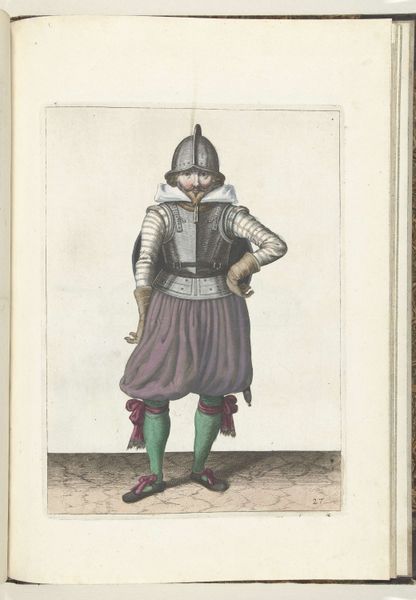

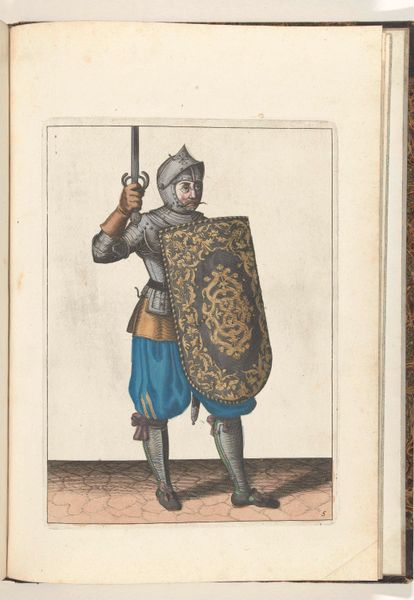

Editor: So, this is *De exercitie met schild en spies: de soldaat presenteert zijn rapier met de hand niet hoger dan zijn gezicht (nr. 19)* by Adam van Breen, created between 1616 and 1618. It's a pen, colored pencil, and watercolor drawing, almost like a page from a manual. I'm struck by how posed and almost theatrical the soldier looks. How do you interpret this work? Curator: This image opens a fascinating window onto the performative aspects of militarism and identity in the early 17th century. Van Breen wasn't just depicting a soldier; he was capturing a specific exercise, a kind of choreography of power. Consider the social and political climate – the Dutch Republic was solidifying its independence. How might this image speak to emerging national pride? Editor: I hadn't thought of it as 'choreography'. It definitely has that feel! The stance seems almost… flamboyant, especially with those puffy trousers. Curator: Precisely! The clothing itself becomes a signifier. It reflects a culture where appearances mattered immensely, where masculinity was actively constructed and displayed. What does the contrast between the ornate shield and the soldier's somewhat awkward pose suggest to you about the artist’s intent, or perhaps about societal expectations of soldiers at the time? Editor: Maybe it’s highlighting a gap between the idealized image of a soldier and the reality of… well, posing with a sword? Like a critique of militaristic vanity? Curator: It could certainly be read that way. And think about the book format – suggesting accessibility, almost like self-help. Is the artist just documenting, or is there an element of satire? These kinds of images, though seemingly straightforward, participated in complex cultural dialogues about war, status, and national identity. Editor: I see it now – it's so much more than just a picture of a soldier. It's about how soldiers, and maybe even the nation itself, were presenting themselves. Curator: Exactly. Art gives us unique access to how identity and power were negotiated in the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.