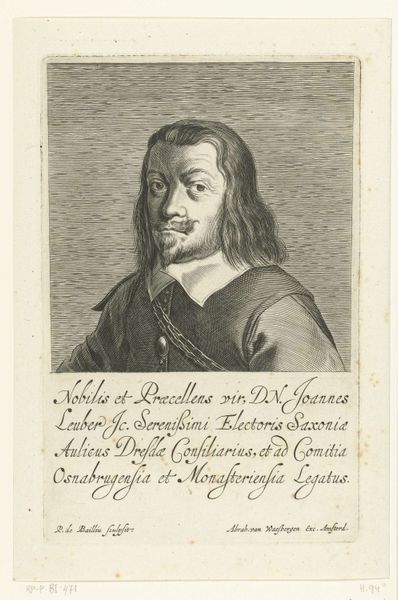

Portret van Claude de Chabot markies van Sint Mauritius 1623 - 1660

0:00

0:00

print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

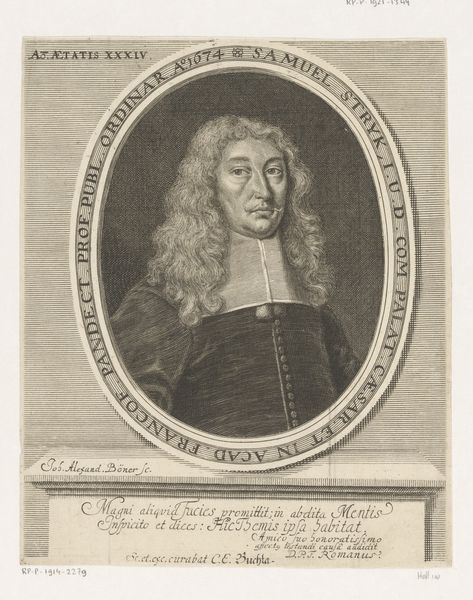

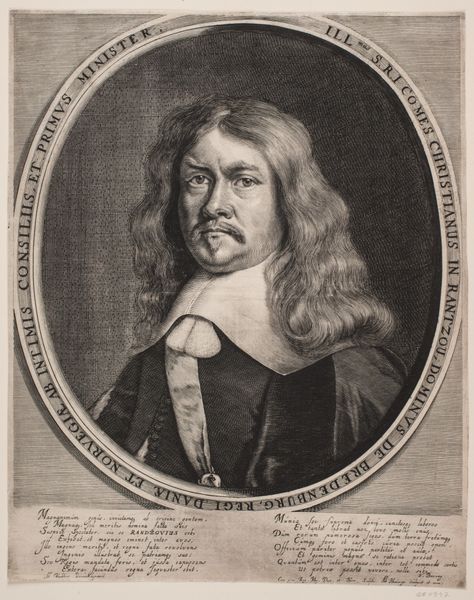

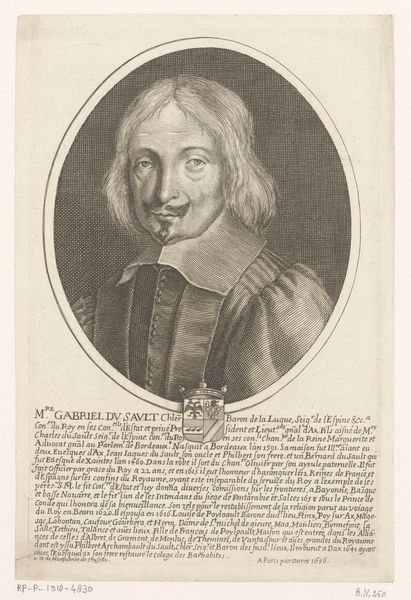

Curator: Here we have Pieter de Bailliu's engraving, a "Portret van Claude de Chabot markies van Sint Mauritius," created sometime between 1623 and 1660. It’s currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: First glance? It's a stoic fellow trapped in time, a baroque gentleman sealed in monochrome. The detailing in his face almost fights with the clean, sharp lettering below, which looks incredibly crisp despite its age. I can't help but feel a melancholic sort of weight in all those tightly hatched lines. Curator: That weight likely comes from the deliberate process. Engravings like this required tremendous skill and time. De Bailliu, presumably commissioned for this work, had to meticulously carve the image into a metal plate, probably copper, which would then be inked and pressed onto paper. Each line you see is a deliberate act. Editor: So, almost an industrial way of art making, you might say. The result is that incredible textural detail, especially in rendering things like his doublet or the way his hair waves – each one has this life etched into the surface. How do you feel about the rigid, formal qualities imposed by this medium versus say paint? Curator: Well, prints like these were designed for dissemination. Think of them as early forms of mass media, reproducing images and solidifying the social status and memory of the subject—a marquis in this case. There’s a purpose beyond aesthetics here; the materials directly influence how society perceives him. Editor: I find myself questioning if we lose some of the individual’s spirit? The print lends a certain gravity, but almost too clean. And while beautiful, there's a rigidity in it compared to a brushstroke, something almost democratic, or humanized by imperfection. It's all business for this Marquis, isn't it? Curator: Perhaps, but that rigidity also communicates authority, a specific kind of power linked to his station and its visibility. The material processes reinforced these established societal structures. Without those factors, would this subject retain the same gravitas centuries later? Editor: I suppose that answers my question pretty clearly. Thinking of those material origins makes the way we see everything a reflection of the time it's representing. All those sharp lines almost vibrate with purpose—history made permanent through ink and pressure. Curator: Exactly. And when considering de Bailliu's engraving here, we gain insights into production, consumption, and even how early modern society used images to construct power itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.