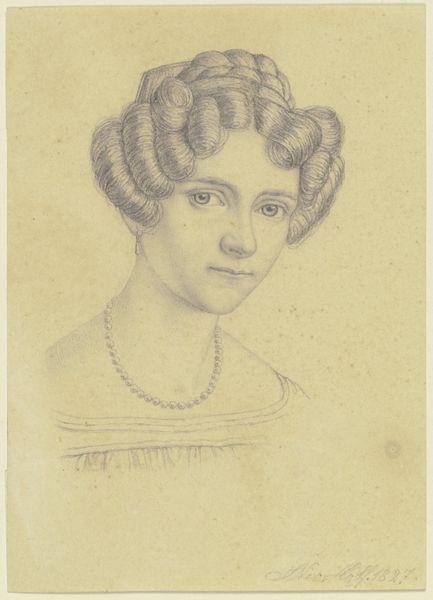

Portrait of a Young Woman 1520s - 1530s

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 6 15/16 x 5 1/4 in. (17.6 x 13.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Pier Francesco Foschi’s “Portrait of a Young Woman,” a pencil and charcoal drawing dating from the 1520s or 30s, now residing at the Metropolitan Museum. Editor: There’s something so tender about it, almost fragile. Like catching a glimpse of her thoughts as she poses, trying to hold still. The simple line work has this delicate beauty, you know? Curator: Foschi, like many artists of the Italian Renaissance, engaged with detailed preliminary studies. This wasn't merely about capturing likeness, it was about refining an idea, and working towards perfection in material form, testing and mastering his means of representation through drawing first. Editor: Absolutely, it’s a window into the artist’s process, the way he’s built up the tones with layers of hatching…You can see him thinking with the pencil, experimenting with the fall of light on her face. It’s so direct! There are corrections there, changes, little shadows and ghosts of ideas underneath the finished portrait. You just don't get that kind of immediacy with oil paints. Curator: Indeed. Consider the societal context: portraiture in that period was increasingly about projecting status, wealth. This work shows that the materials used were important and served a purpose. Drawing materials afforded both accessibility and a chance to easily correct mistakes as part of preparation. Editor: Though the drawing remains unfinished. You see the barest hint of her dress, this kind of wispy suggestion... and the soft focus somehow heightens her gaze. It’s more about conveying a fleeting emotion, a certain inner life, wouldn’t you say? Rather than the cold display of wealth as you find with a lot of commissioned oil paintings. Curator: A worthwhile observation, indeed. We see this medium's utility to capture life while subtly showcasing it through the materiality of the work itself. The visible charcoal and paper connect the portrait to its tangible origin. Editor: I find I’m drawn to its quiet intimacy. So different from the grand portraits you usually see from the time. I mean, it feels less posed and more like an observation. Curator: Yes, considering the work through both the materials and also as a piece of observational life study expands the possible understandings. Editor: A quiet reminder, perhaps, that there's beauty to be found in the in-between moments, the works in progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.