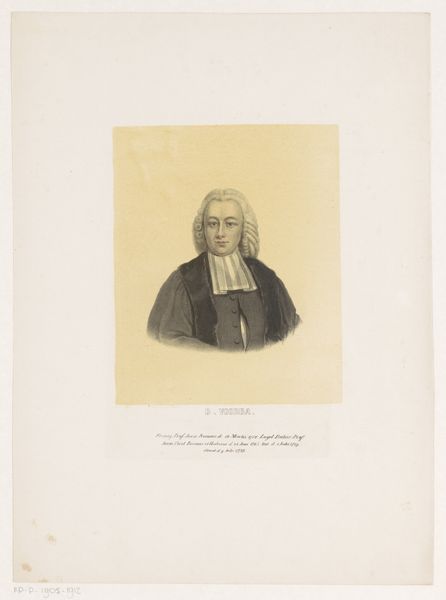

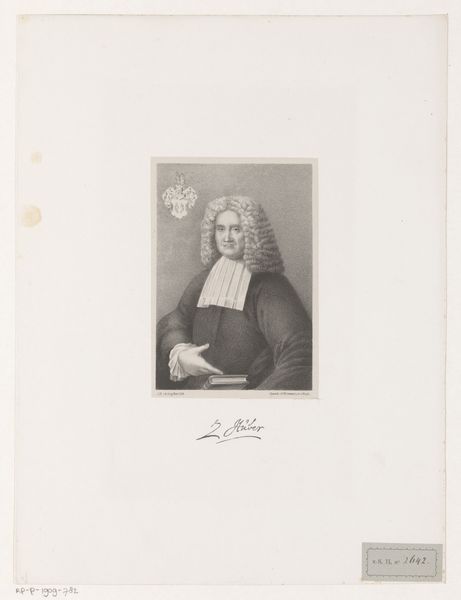

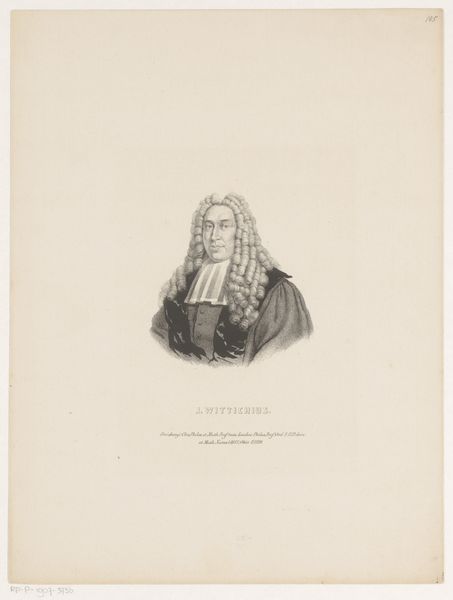

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 346 mm, width 261 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

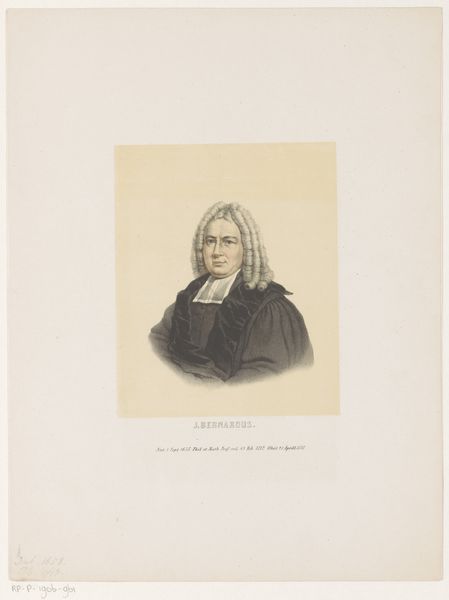

Curator: Welcome! We're looking at "Portret van Petrus van Musschenbroek," a drawing from around 1850 attributed to Leendert (I) Springer. It's rendered as an engraving or print. Editor: My first thought is formality. The subject seems posed, stiff even, like those eighteenth-century scientific portraits intended to project gravitas and intellectual rigor. Curator: Indeed. Musschenbroek, depicted here, was a renowned Dutch scientist. Portraits of this nature served as more than mere representations. They helped cement one’s place within a particular pantheon. Look at the robes, for instance. Editor: And the wig! I am always fascinated by the materials used. The fine lines, created through engraving techniques, allow for incredible detail. It also had to be reproducible on a potentially grand scale. It implies the expansion of images to wider markets facilitated by printing. Curator: Precisely. The rendering of the wig symbolizes status but also speaks to codes of conduct in his profession. Its whiteness is meant to portray knowledge, truth. Editor: I find myself wondering about the labor involved. Who exactly created this engraving, how was it distributed, and how did it relate to the networks of scientific exchange during the period? We so often focus on the sitter. What was Musschenbroek really involved in? Was he actively collaborating on it, perhaps providing some symbolic tools as a prompt to depict his expertise? Curator: An excellent point. These portraits acted as symbolic tools to establish authority. They also tell us what symbols society agrees embody power at that given point. The way he is framed here, against a rather undefined space, almost levitating, evokes a saint or philosopher. Editor: Agreed, the almost ethereal effect adds an interesting layer, considering his contributions were in the realm of tangible science and physics. We might also discuss the cultural consumption patterns and how portrait prints catered to bourgeois aspirations. Curator: A wonderful synthesis of thought and production. By understanding not only the person represented but also the processes that led to their visual immortality, we appreciate not only the artist's labor but society's hidden labor. Editor: Thanks for pointing me toward the intersection of material conditions and status. The artist and printers allowed Musschenbroek's achievements to achieve far reaching influence!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.