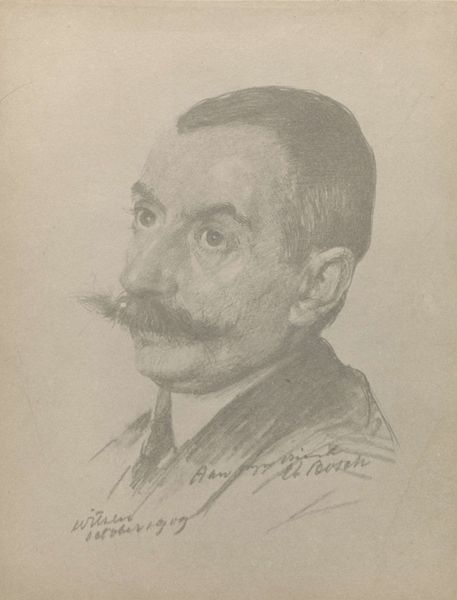

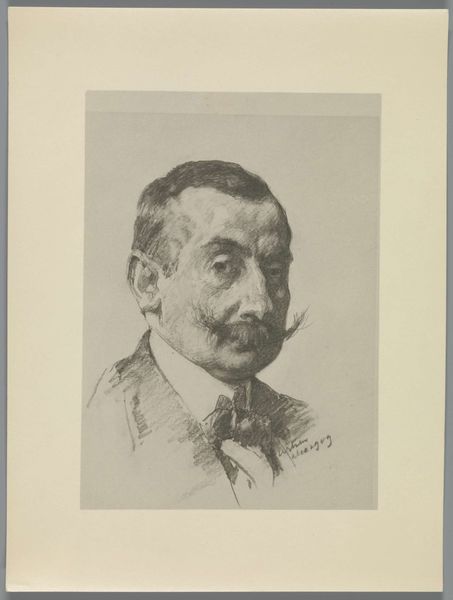

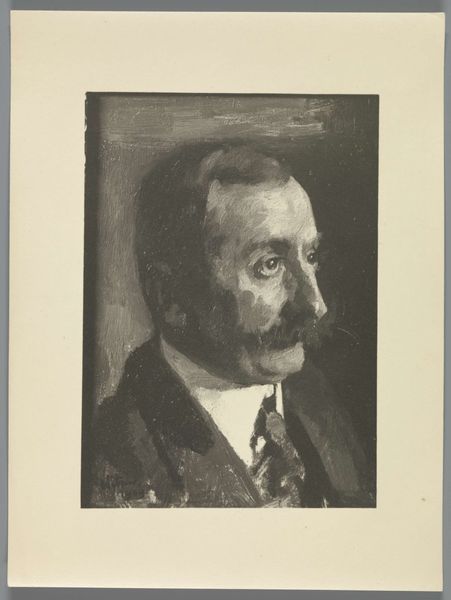

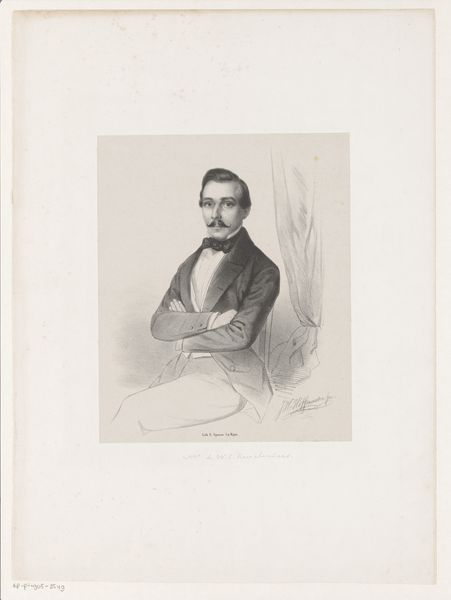

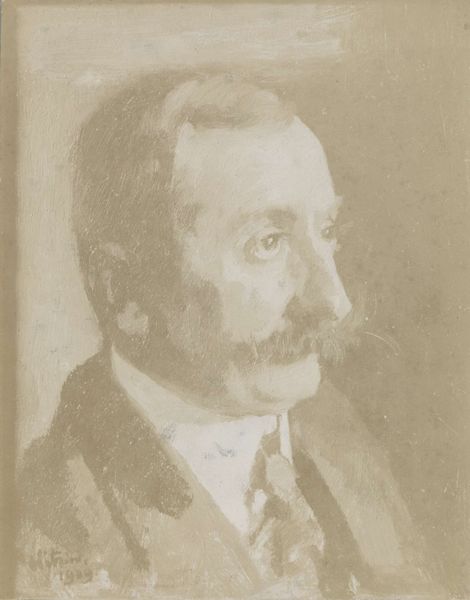

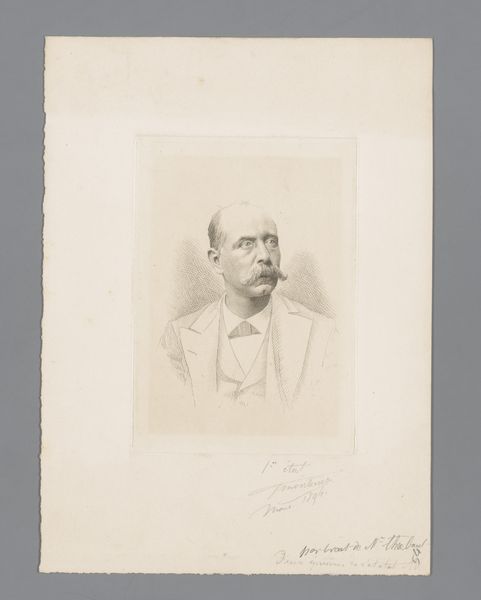

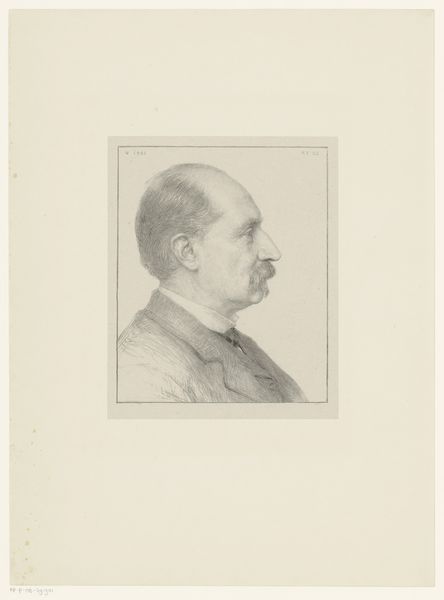

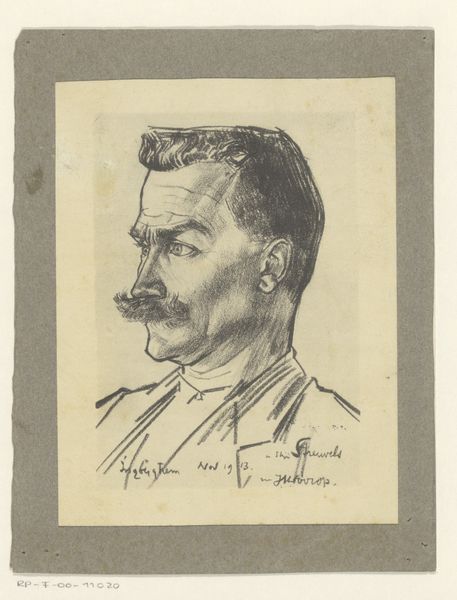

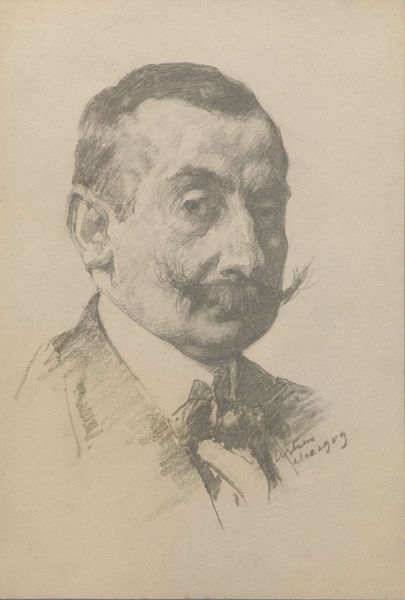

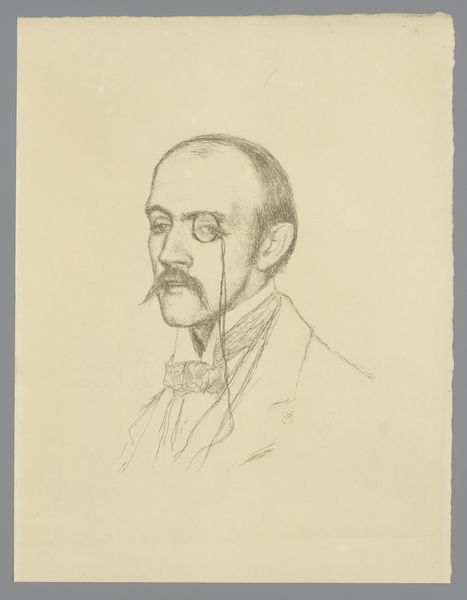

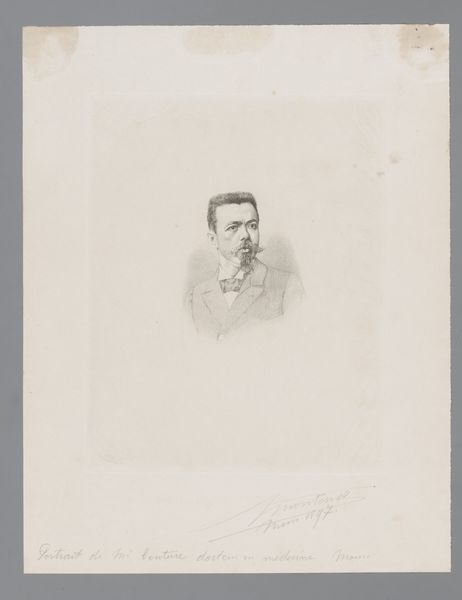

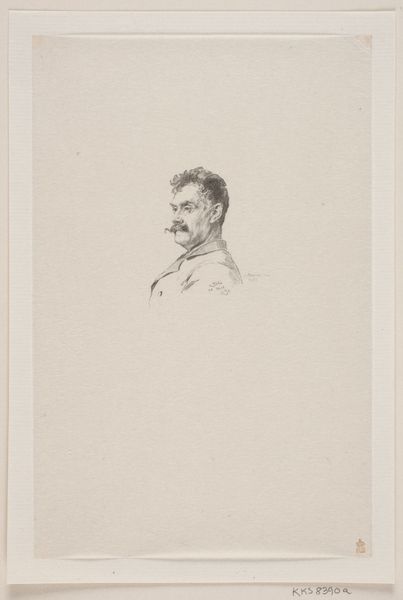

Reproductie naar een foto, schilderij, tekening of prent c. 1860 - 1915

0:00

0:00

diversevervaardigers

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 194 mm, width 147 mm, height 282 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have a drawing listed as "Reproductie naar een foto, schilderij, tekening of prent," which translates to Reproduction after a photograph, painting, drawing, or print. It was created circa 1860-1915 by various makers. Editor: It's a starkly rendered pencil portrait of a man, really evocative, a hint of melancholy in his gaze. The texture of the paper is almost palpable. I'm curious, given its nature as a reproduction, about the social function it might have served. Curator: Precisely! Its existence as a copy highlights broader shifts in image dissemination during this period. The rise of photography allowed for greater access to portraiture, which, of course, had an impact on social representation. Pencil drawings like this one were quite common means to make portraits available to those unable to afford photography, widening the audience of the portrayed subject and imagery. Editor: That speaks to the accessibility, the commodification, almost, of portraiture during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One has to ask, who was the person originally represented, and what impact has reproducibility on both the artist and the art’s social meaning? Curator: Yes, consider the labour too—artists produced these portraits, sometimes based on cheap photography. Was it commissioned, was it purely reproductive labor, or done from memory and perhaps presented as a gift? Was this part of artistic training to reproduce already established or publicly recognized images and styles? Editor: Exactly, and that raises questions about the original and the copy, skill and labor. What constitutes value in an artwork when the boundaries of authorship are blurred by processes of mass-reproduction, by economic and societal pressures. It prompts us to consider not only the artistic intent but also the hands that created and distributed the image. Curator: Absolutely. It brings up all sorts of questions around democratization, too. I am compelled by how it functions as an art object but equally interested by its place within culture and history. Editor: I’m interested in those who consume images and how reproducibility influenced societal perceptions and value systems. Curator: An everyday portrait with echoes across many lives. Editor: Making history not about greatness but, simply, the process of living.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.