#

pencil drawn

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

pen-ink sketch

#

limited contrast and shading

#

pencil work

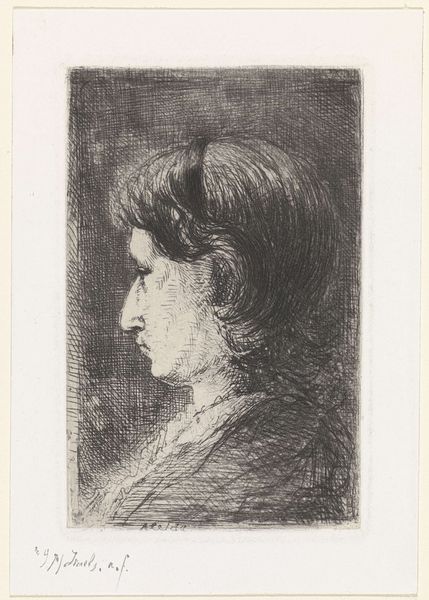

Dimensions: sheet: 48 × 33.5 cm (18 7/8 × 13 3/16 in.) plate: 10 × 6 cm (3 15/16 × 2 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Standing before us is Luigi Conconi's "Ada," created in 1880. This piece is rendered as a print, showcasing the artist's skill in capturing delicate details. Editor: It’s a somber work, isn't it? The shading gives her features a kind of melancholic gravity. Curator: Indeed. Conconi worked during a period of significant social change in Italy. Consider how portraiture, historically reserved for the elite, began reflecting broader societal layers. These images could be commissioned by an emerging middle class, impacting the traditional patronage system of the arts. Editor: Her hat… It seems more like a marker of status than mere headwear. The subtle adornment—is that a feather?—speaks of aspirations, doesn't it? Hats have often been visual symbols of social mobility. This ‘Ada,’ whoever she was, perhaps saw herself rising in society? Curator: Perhaps. During this era, artistic circles played with realistic depictions while also carefully navigating what they deemed respectable, influencing public perception and social norms through representations. Editor: I am drawn to how Conconi depicts her eyes— heavy-lidded, downcast. It almost feels like she's burdened, not just posing prettily. Was the imagery related to ideas about the role of women, beauty standards and expectations? Curator: That's a perceptive point. In late 19th-century Italy, there were emerging discourses about the “ideal woman"— domestic, virtuous, but also intelligent and aware. Consider how Italian unification and Risorgimento ideals influenced cultural outputs, possibly imbuing such portraits with elements of national identity or aspirations. Editor: Looking closer at her bowed head, she resembles classical images of Melancholia –the pensive, intelligent, often frustrated figure that appeared in visual form, since Renaissance. Her gaze turned away, not quite engaging with the world. It connects to the complex expectations society had on young women at this period. Curator: Yes, she is holding many stories and questions within her glance, her dress and this little printed format that was emerging as a very common one! Editor: Seeing all of this offers us the chance to see not only “Ada,” but so much of the culture around her represented in line and shadow.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.