Copyright: Public Domain

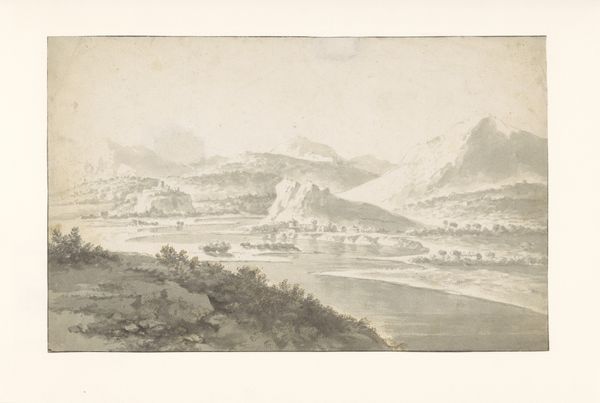

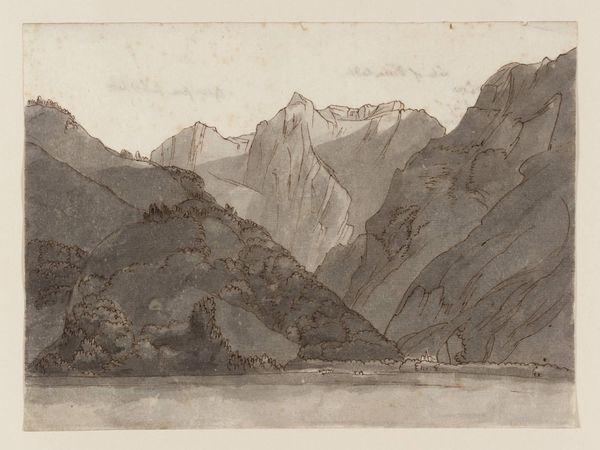

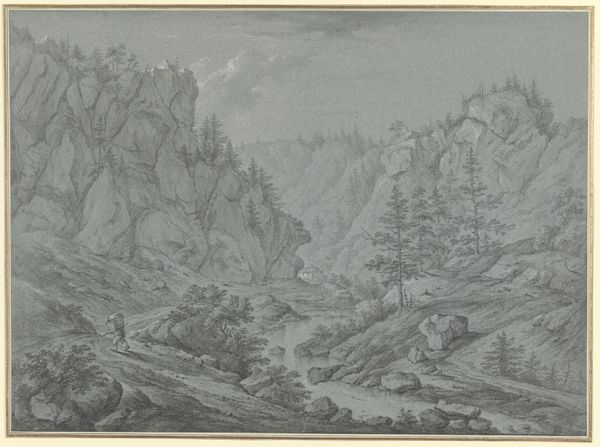

Editor: This drawing, "Innthal von Brixlegg aus gesehen" by Eugen Klimsch, was created in 1873, and it's a pencil drawing. There's something incredibly serene about this landscape, a sense of the vastness and quietness of nature. What captures your attention most when you look at this piece? Curator: It's interesting to consider this drawing within the context of burgeoning tourism in the late 19th century. The Romantic movement's idealization of nature fueled a desire to experience sublime landscapes like the Inn Valley. Editor: So, it’s not just a picture of a place, but about… experiencing that place? Curator: Precisely. How were such landscapes being marketed and consumed? Consider the rise of guidebooks and the increasing accessibility of travel to the middle classes. This drawing could be seen as contributing to the visual vocabulary of that era, shaping perceptions of what an "ideal" Alpine landscape should look like, particularly in a burgeoning nation like Austria-Hungary. The framing emphasizes the majesty of the mountains, dwarfing any human presence, perhaps feeding into ideas of national identity tied to the land itself. Does that alter your sense of its serenity? Editor: It definitely makes me think more about who this landscape is "for." Were these images about access or perhaps even about possession, in a way? Curator: Exactly. Think about how landscape imagery, particularly during periods of nation-building, is used to solidify a sense of shared heritage. This wasn't just about pretty scenery; it was about constructing an idea of "home" – and who gets to belong there. Editor: That really makes me rethink the seemingly innocent nature of landscape art. There are stories beneath the surface! Curator: Absolutely! It reminds us to critically examine how art functions within broader social and political frameworks. This image served its social function.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.