Dimensions: sheet: 25.2 x 20.1 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

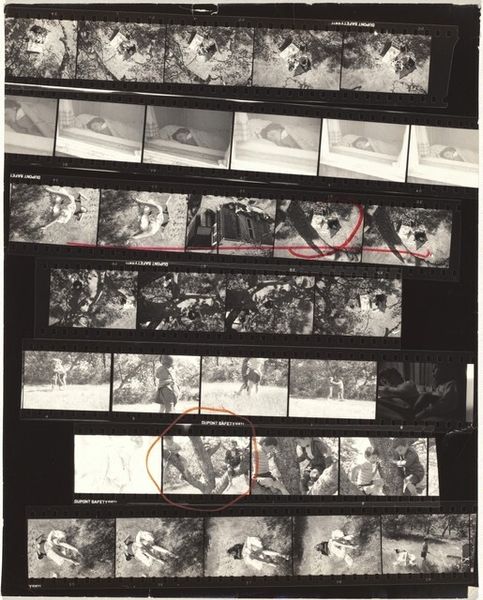

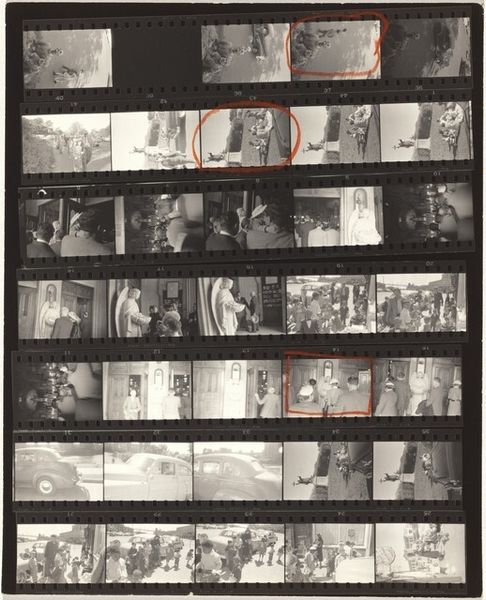

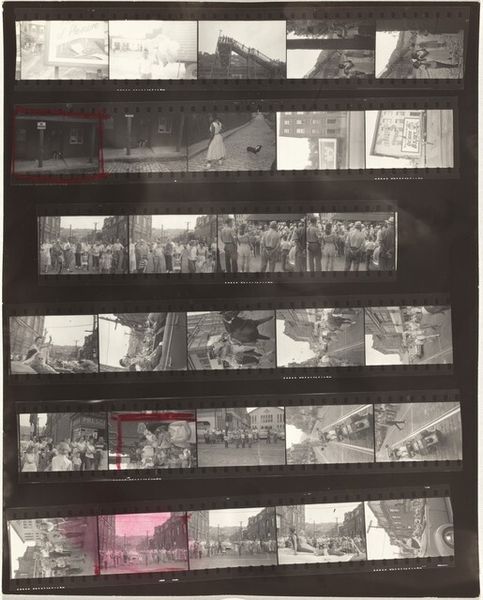

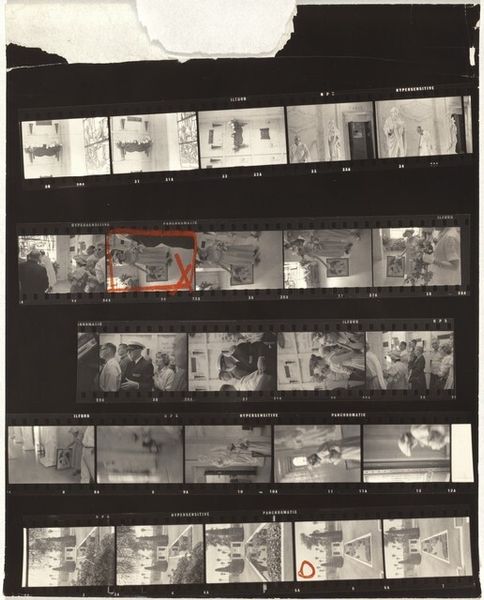

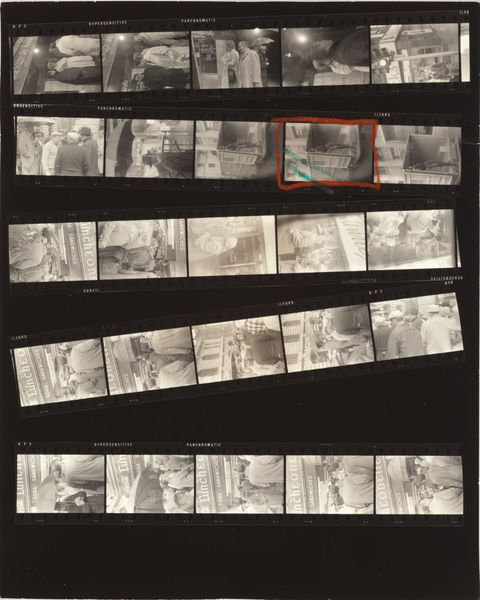

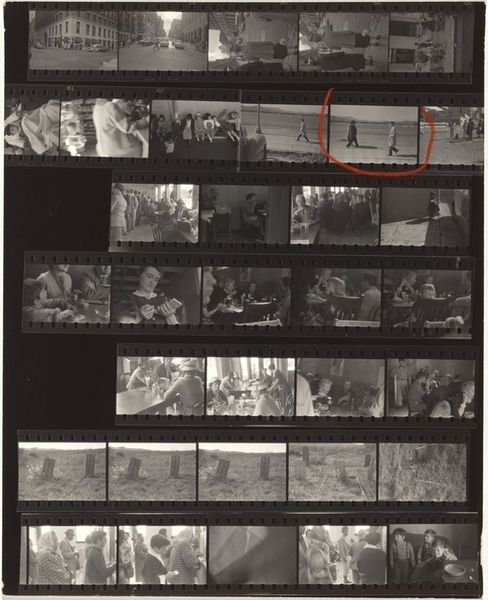

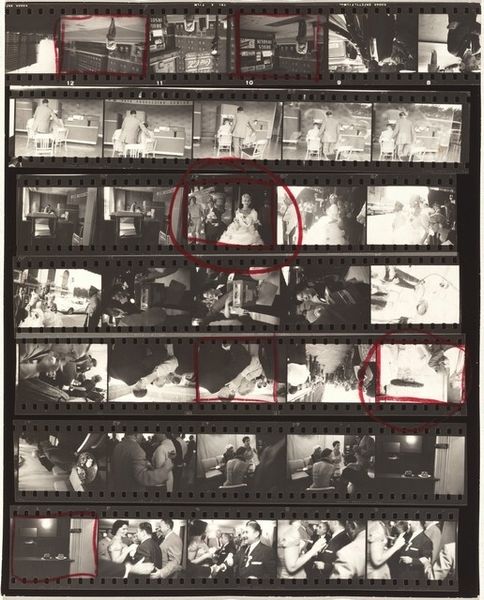

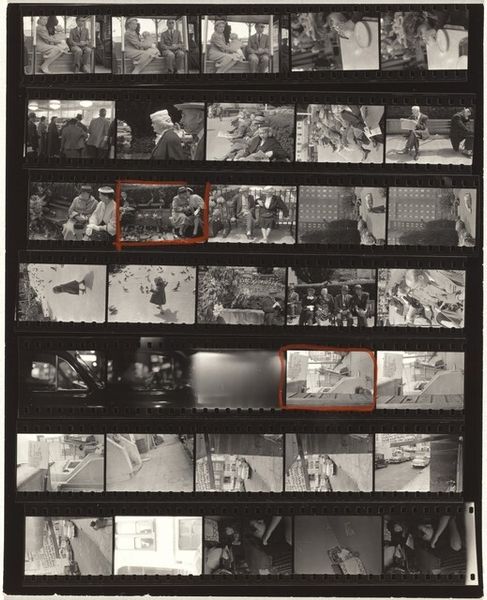

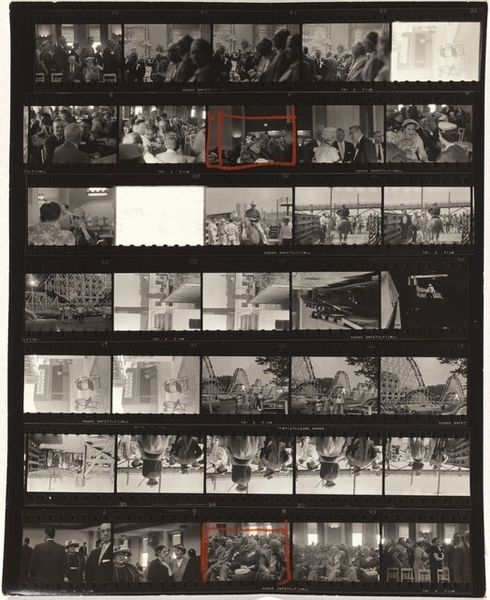

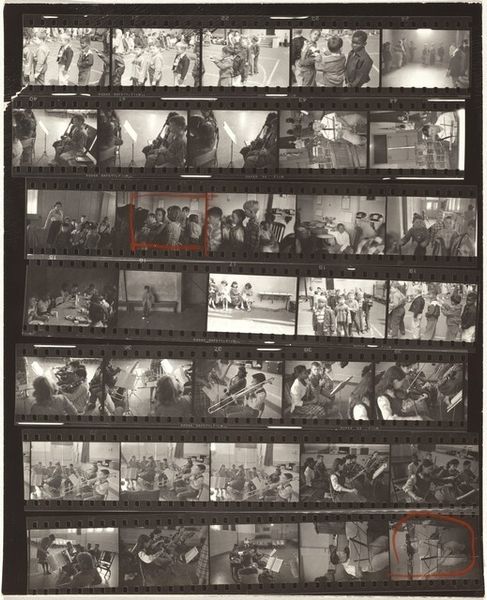

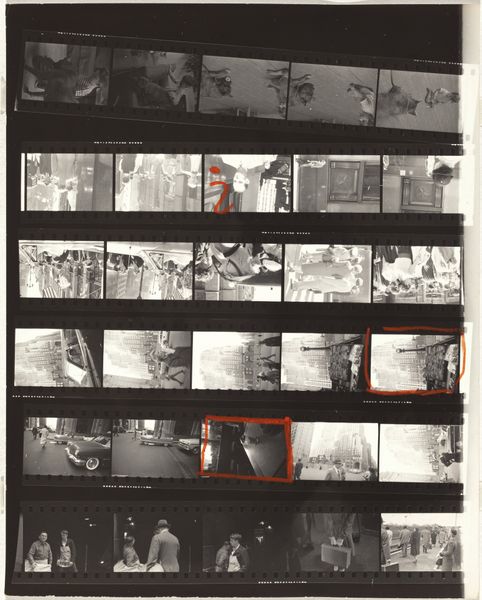

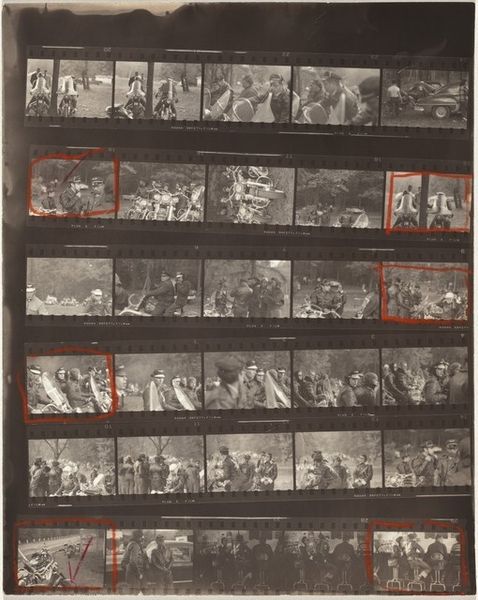

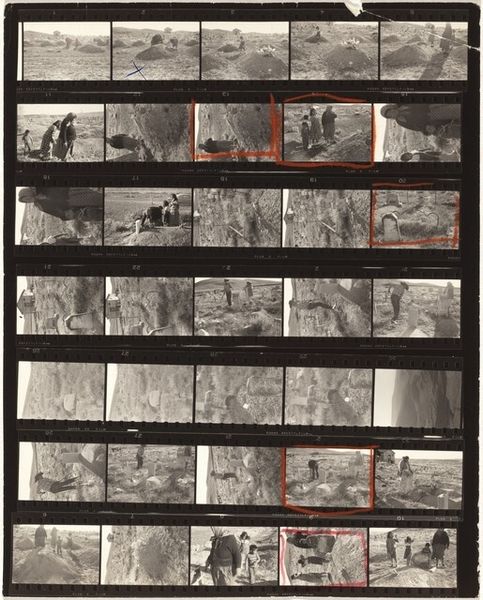

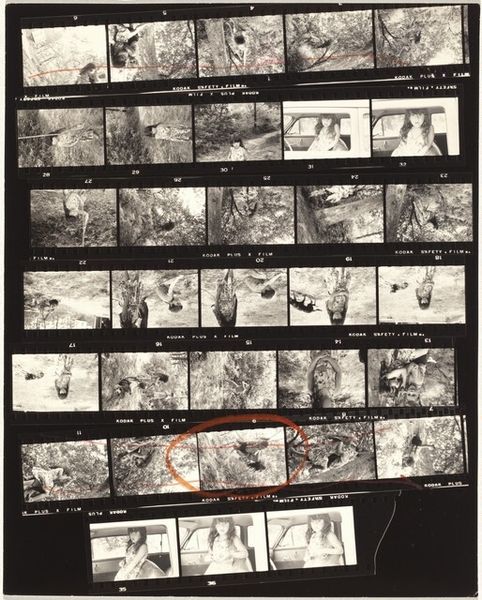

Curator: This is Robert Frank's photographic work, "Pablo going to school no number," created in 1955. The piece appears to be a contact sheet or a series of frames from a 35mm film roll, printed as a gelatin silver print. Editor: My first impression is its raw, almost diaristic feel. The sequencing implies a narrative, but one fractured and incomplete. It's quite a jump from conventional photographic portraiture. Curator: Precisely. Frank uses the inherent materiality of the film strip—its perforations, the text along the edges—to break from the idealized image, signaling his rejection of pictorialism. We’re forced to confront the means of production itself. The materiality asserts the labor behind the capture. Editor: That's a compelling point. And looking closer at the individual frames, you get a sense of candid moments. Street scenes, portraits… snapshots of daily life. Yet, there’s this palpable tension; you wonder about the nature of representation itself when displayed this way. Are we given only select evidence of "life?" Curator: He embraces contingency. Consider the framing, the moments captured, seemingly unposed, with varying degrees of clarity. The way it highlights everyday existences is important; it democratizes the subject matter, rejecting grand narratives in favor of quotidian observations. Semiotically, each frame signifies both a captured instant and a moment irrevocably past. Editor: The contact sheet format emphasizes Frank’s editing process and creative selection and decision making in the darkroom. The arrow drawn onto the emulsion… it pulls our focus toward what he valued or discarded in service of meaning making. Was he successful at capturing or representing that original instance or moment of his own accord, for his own memory? We are unsure. Curator: Indeed. These marks give insight into the construction of meaning that underscores so much of Frank’s work. Each mark acts as signifiers of a process of filtration. The images exist together in service to a larger idea than their discrete contents. Editor: Seeing this film as object versus artwork complicates my perception, and raises the status of labor beyond only the "photographer." I wonder, for all of its seemingly accidental affectations and unfinished quality, about the people or machines involved with industrial manufacturing required to render these photographic effects? What part did they play in image making or visual language we ascribe to art? Curator: That really emphasizes that photographs aren't simply objective documents. The final image owes much to both technology and a material processing history. I see a record of decisive aesthetic choices about what comprises the final presentation of ideas that ultimately rejects all authority or single point perspective on that representation. Editor: It moves past a single definitive image. Viewing his editing offers great possibilities for discussing meaning or intention in photography through social realities, materiality, or representation beyond aesthetics. Thanks for sharing!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.