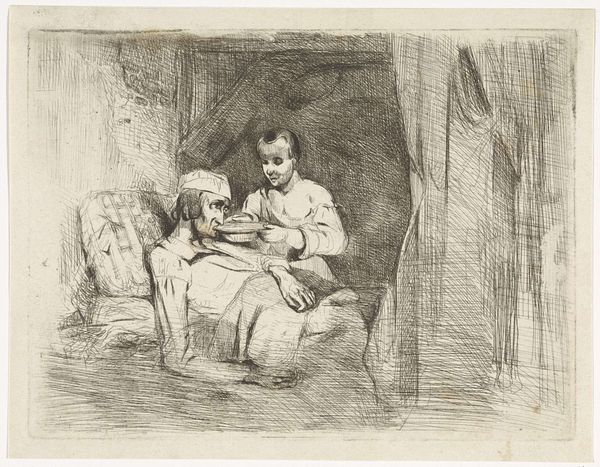

drawing, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

narrative-art

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

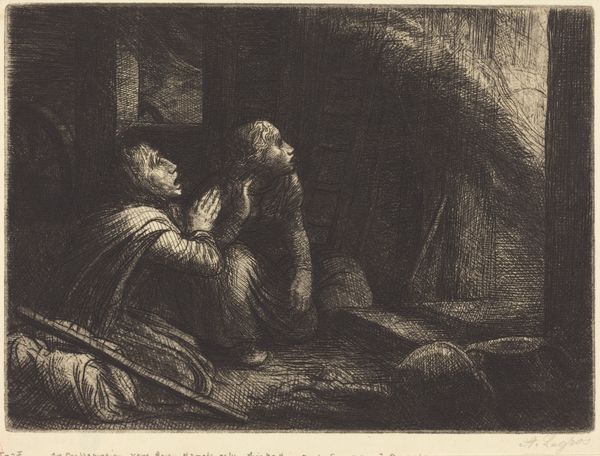

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

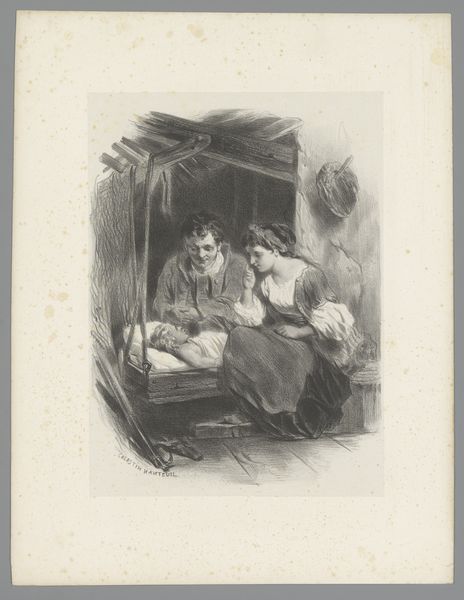

Curator: This poignant drawing, dating from between 1829 and 1849, is by Petrus Marius Molijn. It’s titled "Zieke man krijgt te drinken," which translates to "Sick man getting a drink." It seems to be executed in pencil and ink, featuring delicate lines and shading. Editor: My immediate reaction is quiet sympathy. The lines are so fragile, the scene so intimate. There's something heartbreakingly tender about it, almost as if we're intruding on a private moment. It reminds me of trying to care for someone who is really unwell and the exhaustion of both parties. Curator: Yes, intruding feels apt. Consider the context of the 19th century. The work reflects a growing social consciousness and a focus on everyday life and ordinary people. These intimate, vulnerable portrayals offered an implicit critique of societal inequalities and lack of access to proper medical care. The composition, with its emphasis on light and shadow, also pulls us into a shared feeling of concern. Editor: Absolutely. The sketchy nature somehow enhances that immediacy. It doesn't feel staged or posed, but captured on the fly as a glimpse into lived reality. It makes me think about the invisible labor of care and how it disproportionately falls onto women and other marginalized groups. Curator: Precisely. The illness becomes a kind of mirror, reflecting broader societal ills and the burden placed on certain individuals within a social system marked by profound disparities. The drawing speaks volumes about gender roles and expectations. This could very well be read as a snapshot into their relationship where care falls on certain individuals rather than being distributed as a form of common care. Editor: Thinking about it now I realize I had jumped to assumptions that it was a family relationship! In the intimate reality, we have to ask if this reflects a care relationship for which some were and are paid for rather inadequately? Curator: That is a powerful shift in perspective and definitely challenges what might appear as only one, more benign way of reading the artwork. It underlines its strength as a document reflecting on human connection and obligation. It also suggests lines of intersectional analysis. The image seems almost humble, but prompts some very current concerns. Editor: And it does all this without grandstanding, without being didactic, it asks us simply to witness. Its simplicity gives it a resonance that lingers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.