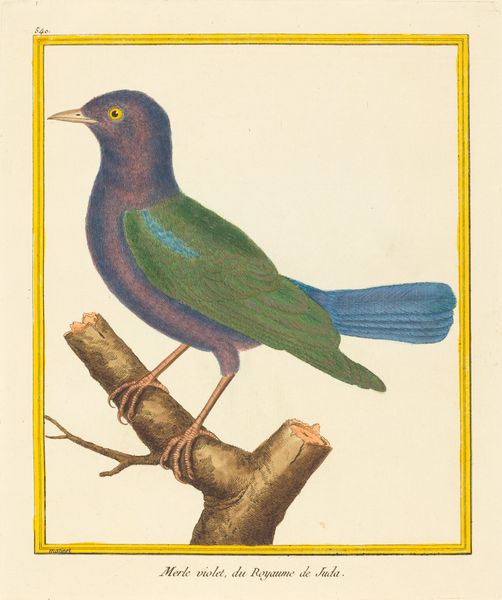

drawing, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

naive art

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 253 mm, width 403 mm, height 238 mm, width 403 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Coracius garrulus (European roller)," a watercolor drawing, possibly from between 1777 and 1786, by Robert Jacob Gordon. It's a very charming and detailed illustration of a bird. I'm curious, what sociopolitical narratives do you think this piece engages with, if any? Curator: That’s an insightful question. These natural history illustrations from the late 18th century weren't simply objective recordings of the natural world. Gordon, as a commander in the Dutch East India Company, was implicated in the colonial project. His depictions, while seemingly innocent, helped classify and possess the land and its resources for European interests. Have you considered the role of scientific illustration in advancing colonial agendas? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't fully considered. So, you're saying these types of illustrations served a purpose beyond just documenting species? Curator: Precisely. Think about who had access to this knowledge and how it was used. Scientific illustrations became tools for asserting control over the environment and its inhabitants, subtly reinforcing the racial and economic hierarchies of the time. What do you make of the bird's pose in relation to these ideas of ownership and dominion? Editor: The bird seems rather passively posed. Maybe that reflects how the colonizers viewed the land and its resources – as passively available for their use. Curator: Indeed. Understanding the historical context helps us deconstruct what seems like a straightforward depiction and uncover the underlying power dynamics at play. It is so very important to ask critical questions about art production and reception. Editor: I see the image in a new light now, as more than just a pretty bird. Thanks, this gives me a lot to think about regarding the artist's intent. Curator: Absolutely. And it reminds us to interrogate whose perspectives are privileged and whose are marginalized, even within seemingly objective forms of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.