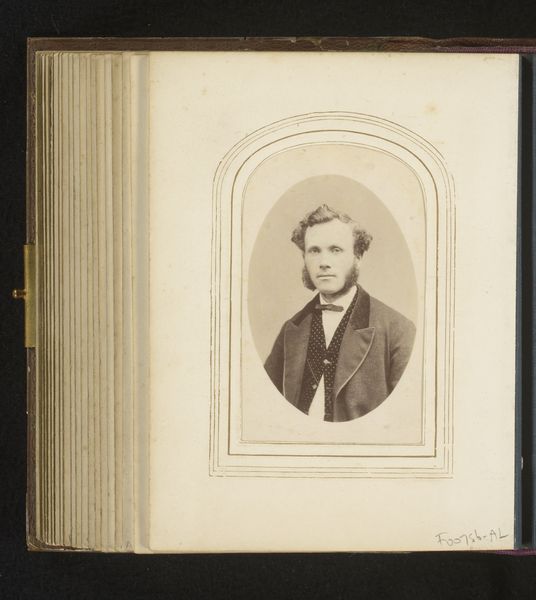

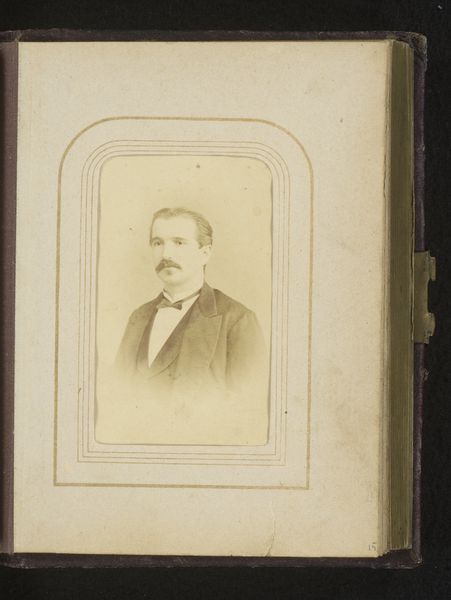

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

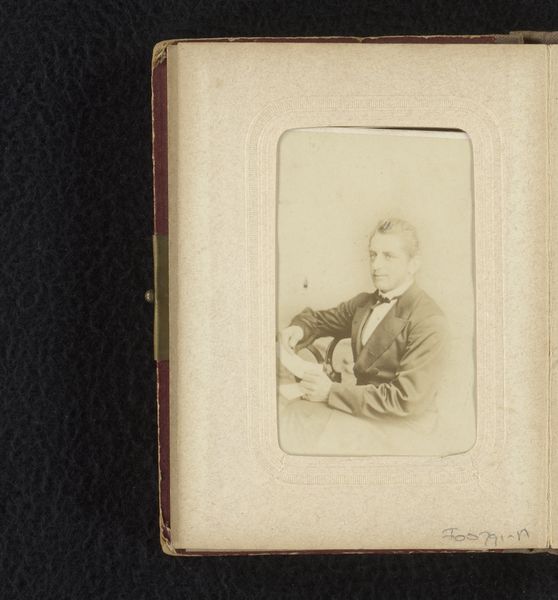

Curator: Here we have "Portret van een jonge man," or "Portrait of a Young Man," a gelatin silver print likely taken between 1860 and 1900 by Roelof Hinderikus Christiaan Karsses. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the portrait's austerity. The oval frame within the larger album page isolates the young man, emphasizing the severe lines of his suit and the stark, almost somber lighting. It feels very controlled. Curator: That controlled atmosphere is very much a product of the era. Portrait photography at this time was as much about projecting status and respectability as it was about capturing likeness. Editor: You can see it in the sitter’s careful pose and expression. He's clearly meant to embody seriousness and perhaps even a hint of Romantic-era melancholy with those heavy-lidded eyes. Curator: Photography democratized portraiture to an extent, making it more accessible to the middle class. But this democratization came with its own set of rules about how one should present oneself publicly. The choice of clothing, the carefully arranged hair, all of this speaks to the rising bourgeoisie class wanting to show that they were as worthy as those of noble blood. Editor: Indeed. Notice how the monochromatic palette—almost a study in shades of gray—amplifies the focus on form. The sharp contrast around the face against the muted backdrop is clearly meant to direct our gaze. Curator: And this brings up another element—these photo albums served an important social function. They became a means of curating family lineage, reinforcing class identity, and making visual arguments about who belonged and who did not. Editor: I agree completely. Looking at it through a formal lens, it really displays the conventions and limitations—or perhaps, controlled articulations—of self-representation at the time. It's both artful and, in its own way, incredibly artificial. Curator: Ultimately, photographs such as these served to solidify those social structures. Editor: An astute analysis of a work, so seemingly simple, yet so historically laden.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.