drawing, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

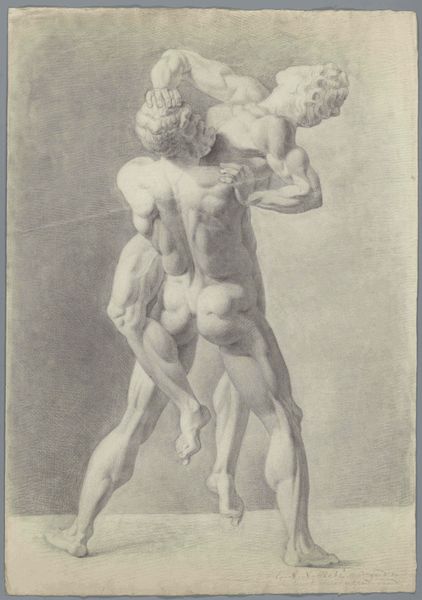

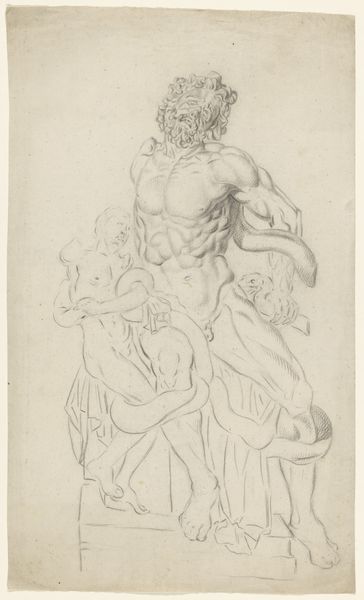

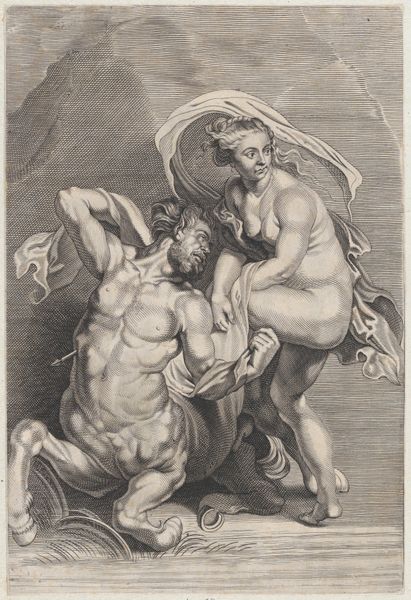

Dimensions: height 564 mm, width 329 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

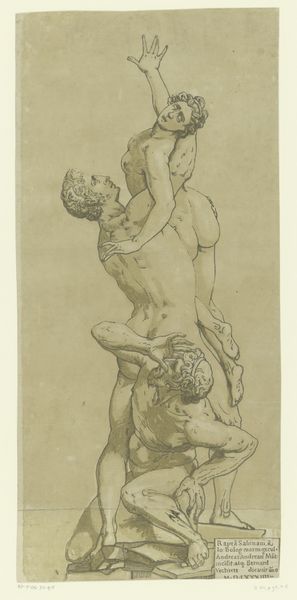

Curator: The figures in this pencil drawing are locked in such fierce combat; I'm struck by how much raw physicality is communicated with a relatively simple medium. Editor: Yes, it's interesting how Cornelis Joseph d’Heur uses pencil to translate the monumentality of a sculptural group. This piece, titled "Copy after a Sculpture Group of Hercules and Antaeus," produced between 1717 and 1762, reduces a complex three-dimensional object into something readily reproducible. Curator: Absolutely. The choice of pencil also highlights the process of replication. D’Heur wasn't just copying; he was meticulously studying form, shading, and proportion, all by manually transcribing it with readily available tools. The texture of the paper itself becomes crucial here, doesn't it? Editor: I think so. The drawing is also referencing the very political narratives these classical myths embodied. It suggests ideas about power, dominance, and even the justification of imperial endeavors prevalent in European society at the time. We see Hercules, representative of civilization, defeating Antaeus, who is rooted in the earth. Curator: That's right, and we must consider the economics of art education, where copying sculptures, especially antique ones, was core. Pencils, paper, and the accessibility of these reproductions created a cottage industry around art-making. It becomes a question of democratization, if one were able to learn classical form through affordable materials. Editor: Precisely. What the drawing communicates is deeply embedded in a network of access. What does it mean to only access power via drawing as a tool? By depicting this mythological battle, is D'Heur subtly commenting on the futility of physical struggle in an increasingly literate society? Curator: I see your point about it all tying into power and representation. But for me, it highlights the intense labor required to understand the classical canon. Every line, every shaded area, speaks to the process of translating immense ideas into manual action and material understanding. Editor: In a way, by reproducing and reframing that dialogue in the 18th century, D’Heur opened the original sculptures up to wider audiences, allowing new avenues of interpretation. Curator: Yes, indeed! And in turn, we’ve arrived at a further layered discussion about labor, materiality, and political history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.