#

portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

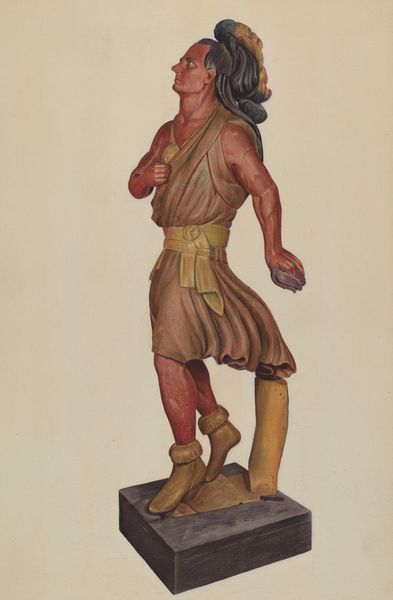

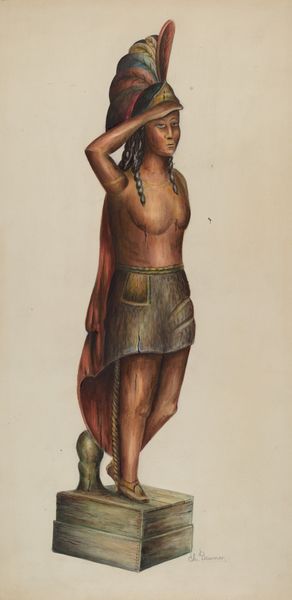

Dimensions: overall: 57 x 30.5 cm (22 7/16 x 12 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This watercolor and charcoal drawing, "Cigar Store Indian," dates to around 1939 and is attributed to Charles R. Shane. It’s a rather striking portrait, isn't it? Editor: It is that, yes, but there is something haunting about it. A stoic figure depicted, presumably, for commercial purposes but tinged with a melancholic air. The mix of materials—watercolor for the skin tones, charcoal for that striking cloak—really draws me in. Curator: The figure itself embodies a complex and troubling history. These sculptures were once ubiquitous, placed outside tobacconists to attract customers. Their appropriation and misrepresentation of Indigenous people is, of course, deeply problematic. Editor: Absolutely. I’m wondering about the making of this specific artwork though. The choice of media seems key. Watercolor lends a delicacy to the skin, contrasting sharply with the almost brutally applied charcoal. I wonder about the maker's hand in relation to the commercial role expected of them. Curator: That's a key point. Was the artist actively interrogating the complex symbolism, or simply replicating an established and unfortunately harmful stereotype? Considering the social and historical context of the 1930s, what narratives about Indigenous people was this artist perpetuating? Editor: The texture especially is compelling. The feathered details on the garment, likely crafted from roughly textured paper stock that holds the charcoal, feel almost violently applied. Was this Shane making an appeal or statement using process? Curator: Perhaps. The drawing’s existence, within the realm of fine art, offers a space to re-examine that legacy, to confront the uncomfortable truths of cultural appropriation and representation in commercial art. It challenges us to think about who profits from these images, and at what cost. Editor: Precisely. Focusing on the process—the very hands that shaped those charcoal marks, the specific papers, and pigments selected—opens a new line of inquiry for understanding how and why these images were produced, and consumed. A reminder that materials and the acts of making have political weight. Curator: Thank you, this has definitely enriched my appreciation—or perhaps complicated my understanding—of this complicated, intriguing work. Editor: Mine as well, offering fresh insight into commercial art and their production practices.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.