drawing, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

quirky sketch

#

baroque

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

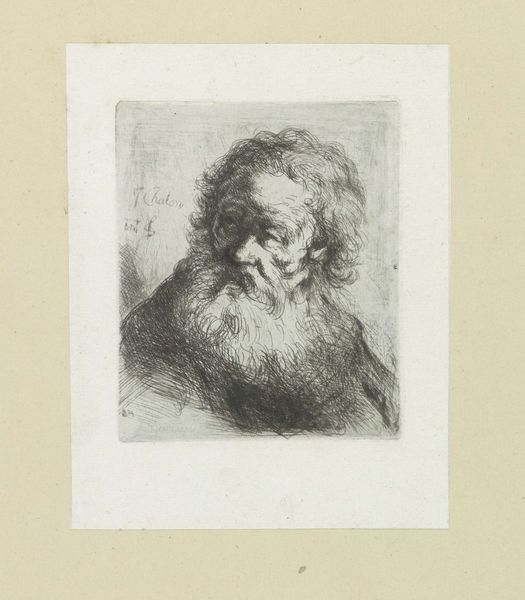

Dimensions: height 66 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have "Head of a Satyr with Beard and Tambourine" by Stefano della Bella, a drawing dating from between 1620 and 1647, rendered in ink. There’s a wonderfully raw energy about this piece. Editor: My initial impression is one of transience, a captured moment. You can almost smell the ink and feel the speed of the artist's hand. The coarseness of the lines lends itself to a certain rustic charm. Curator: Considering Della Bella's historical context, this sketch represents a negotiation between societal expectations of art as representation and an intimate glimpse into Baroque artistic exploration, especially in portraying marginalized or mythical figures. He's really playing with gender and power dynamics here. Editor: Absolutely, the roughness of the execution contradicts the idealization so often associated with depictions of mythological figures. We see the physicality of the marks – the labor, really – that constructed this image. How were drawings like this viewed during the artist's time, and what's their role in relation to his larger body of work? Curator: It’s compelling to look at this now, through contemporary eyes, and recognize a subversive spirit; we're challenged to grapple with ideas about mythology and its complicated intersection with sexuality and societal norms, particularly given the role of the satyr as a symbol of unrestrained freedom. Editor: I find it really interesting how the artist allows the tools to define the subject, there’s no real attempt to obscure the medium. How accessible would this material process be for people observing the artwork at the time? Curator: I believe this is still a really radical engagement in art making. Looking at it now it urges us to challenge assumptions that the art making practices during that period, or even art practices now, should always conform to standards of refinement and prescribed meaning. It suggests to us to reflect more on who dictates these assumptions, and why. Editor: It makes one consider who would commission this artwork and the artist's intentions using readily available, portable tools. A statement on the social landscape during his time, I would say. Curator: It absolutely allows us to look back on 17th century European ideas on identity, and hopefully forwards into creating a future free from restraints. Editor: An authentic peek behind the curtain of art making during the Baroque period. I find its texture really alluring, I feel the connection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.